On my first morning back in NYC, I had a long-awaited dentist appointment. At 8, I walked into the bare bleak waiting room; I sat for a moment looking at the scuffed floor, at sad magazines; a serious 30-ish woman whisked me into a chair, bibbed me, X-rayed me, scraped me, made me lay back and say aahhhh, caused me to gag several times, and at 8:30 AM told me I was fine and to come back in 6 months. I had not been in a dentist’s chair in a wrongly long time, and as I walked by Barney Greengrass on my way home a sturgeon, with dead eyes askew and empty in the window, seemed to warn me not to gloat. How could I repay my teeth? I passed my tongue over them; they were proudly arrayed in my mouth, smug and demanding compensation.

Apparently, as I have been reading over at Soho the Dog, a group of scientists (!) have told a bunch of people to try to be happy and then put Le Sacre du Printemps on the stereo. Then they asked them how happy they felt while listening, and published the results in an academic paper. (Perhaps this last part is the bit that pisses me off the most.) I have to say my considered, scientific reaction to this is: Are you KIDDING me???? For me, the money quote comes when the scientists (?) explain how they came to select Stravinsky’s masterwork. They deduced it was a good, interesting choice because it was “hedonically ambiguous.” Bitter inner laugh. Yes, I suppose you could say that: when the virgin gets sacrificed at the end of a savage, ever more violent, and yet fertility-oriented ritual, that is somewhat hedonically ambiguous. Hello? Clue phone’s ringing, is anyone answering?

Soho, aka Matthew Guerrieri, usually eminently reasonable, seems to suggest that this study means that we shouldn’t do pre-concert talks. Respectfully, I must admit I am missing some of his deductive links. In not one of my preconcert talks have I ever told my audience to be happy, or to have any particular emotion at all; merely, mainly, to notice things; to lubricate the attentive faculties. I’m sure this annoys some audience members sometimes too.

I think the scientific (?) experiment means the obvious: you should never ask people how happy they are. It’s a very irritating question. My happiness goes down considerably when people ask me, and takes a while to recover. (I send my happiness off to a resort in the Bahamas.) The question is often asked disingenuously, as in “of course you’re not happy because you’re work-obsessed and aren’t in touch with yourself, but I’m going to ask it already knowing the answer, because I want to help you figure that out, to take you down the enlightened path that I occupy.” When you blurt through your forced grin, “yes, I’m happy,” people look at you with searing pity, like it’s so sad you can’t admit that you’re not. Then you want to do violent things to them, which most people would agree is not a happy-go-lucky state of mind.

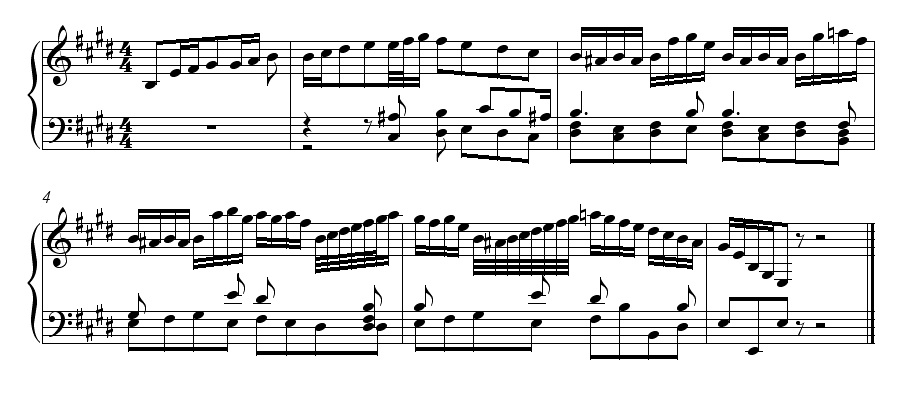

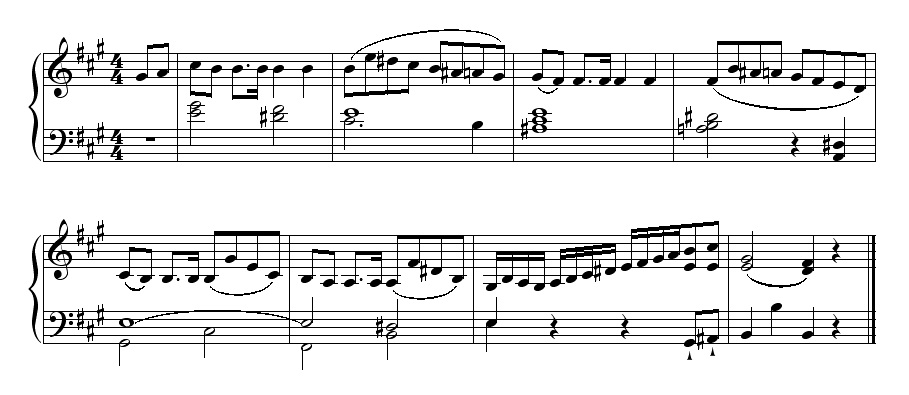

After my dental appointment, and several cups of coffee, a long day of practicing ensued. Was I happy while I was practicing? Well, I didn’t ask myself. I remember lingering for a while on this moment:

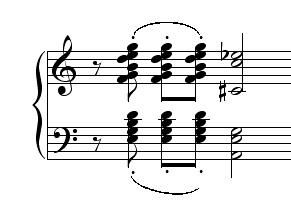

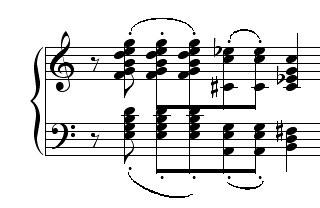

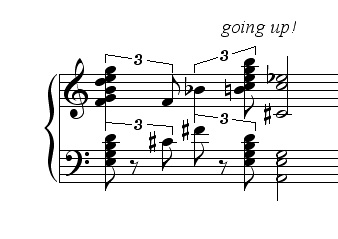

Regular readers of Think Denk may remember that, in place of happiness, I propose the philosophy of the “hap”—a unit of experience. This Mozart theme is crammed with beautiful haps (it is hap-dense). I remember thinking a lot about which of these, which little nooks and crannies in the chromatic descent, are the most wonderful, which were the ones that could be enjoyed without slowing or destroying or distorting the whole, the ones that could somehow feel timeless while being swept up in the current of the piece’s time. I also remember dwelling on this thing:

…. yes the little beautiful bird of a melody which flies into the development unannounced and soars around, then vanishes, only to come back again at the end of the recapitulation … perhaps the generative, magical “hap” in that passage lies in the very first two notes. There is the melody note, a G-sharp, which is prosaically part of E major; but then the underlying harmony shifts to the subdominant, making the G-sharp suddenly a wonderfully dissonant seventh, a sensual, possibility-laden thing. And indeed that dissonance as a jumping off point becomes the occasion for any number of leaps and dialogues wandering from right to left hand, from treble to bass (a series of interlocking joys), all wrapping itself up perfectly into the sentence known in music as the phrase, the delimiting frame, the little package which makes it possible to absorb the beauties within and not to get utterly lost in them.

But then, at 7 PM, post-mortem-ish, delirious, sitting in the train, on my way to a friend’s birthday party, lost in my thoughts, I realized that while part of my brain was feverishly caressing Mozartean nuances, unable to let go, another considerable portion of my brain was replaying certain moments at around 8:12 AM; I was reminiscing automatically on the scrape of metal tools on the borders of my gums. For a moment, as the subway whizzed, I was looking around a room from a prostrate position, a paying prisoner, trying desperately to keep my mouth open (while instincts screamed protect yourself! flee!); nonetheless I remembered this prostration with some sort of pleasure, some happy misery. Lovable haps were crammed in this memory, even down to the chalky fluoride, the 70s wood grain of the fixtures, the concise bzz of the X-ray machine … I wasn’t at all sure I wasn’t remembering this moment with more love than Mozart had forcibly wrung from me all afternoon. I passionately mused over my early dentistry and made a melody out of its suffering.

A man across the car from me was visibly absorbed in a book. I couldn’t quite make out the title, though the cover seemed to be in an interesting design, and the man—how should I quantify this?—seemed so happy reading it. I admired him. He was vaguely smiling, and was not at all distracted when a group of three men entered the subway car and began to sing gospel, very loudly. They exhorted us, all of us in the car, to be happy. “Smile,” they said, “it won’t mess up your hair!” I could feel myself fighting dark urges. Other people on the train felt the same way. The singers held out their cup to me as they passed and I looked at it scornfully, despite my better self, which looked on with rolled eyes, thinking grow up, Jeremy. It’s not their fault they’re happy, I thought, but no smile leaked from the faucet of my face.

59th Street. The happy reader was getting off! As he exited, I managed to glimpse the cover of his volume: it read, neatly printed, THE POCKET GUIDE TO UROLOGY.

Another passenger came and sat in his place. I had but one more stop to go and my eyes briefly rested on this new arrival. Hmm. There was something familiar about her. I couldn’t quite place it. It was only when the train began to creak and groan, and make preparations to exhale me … only then I realized that despite absence of mask and glove and other gear, this was my dentist. She was stoic. I tried to look at her, get some eye contact, to send mental vibes saying “you made me happy with your fluoride procedures, somehow,” or “I was just thinking about you!” but she read none of my vibes and looked nowhere and everywhere, her eyes evasive and yet still, like the sturgeon in Barney Greengrass. How many mouths had she reached into since mine, while I had sonically manipulated my 88 black-and-white teeth?

Her reappearance unnerved me. I felt dazed by unmeasurable correspondences; I felt framed. As I strode down 51st Street to my destination, I had only one sure conviction. If a scientist comes up to you and asks you to measure your happiness, on a scale from 1 to 10 or A to Z, or whatever, I give you permission to use as many expletives as possible (to employ cuss-dense, hedonically ambiguous formulations, if you will). This may do wonders for your personal happiness; it will be a hap to cherish.