The sun cannot sleep, and neither can I. I am up (up!) at ungodly 5 am, wearing all brown for some reason, on the first post-solstice day. A friend from NYC emails: “how’s Michigan? can you see the stars?” Yes, there is one star I can see very clearly now, it’s only about 93 million miles away, and I was watching it come up over a line of trees from a paddle boat; also I was watching my waves disturb the water’s peace. I pedaled one small revolution-fraction; then watched the tiny effects of my tiny motion wash off in beautiful wavelets, barely changing the surface of the water: long wise shivers, like the ripple of an elephant’s skin. Then, when my troubles had dispersed, a genial breeze came and the surface in the early light became like a fantastic evanescent chessboard, like chess you’d play in the 15th dimension, ever changing squares, diamonds, vertices, an infinite complexity of motion. As the sun rose, the light became plainer and plainer and these effects vanished. (But they seemed quite real, for vanished effects.) I climbed the hill, brownly, and put on a pot of coffee (blackly); it was going to be one of “those” days.

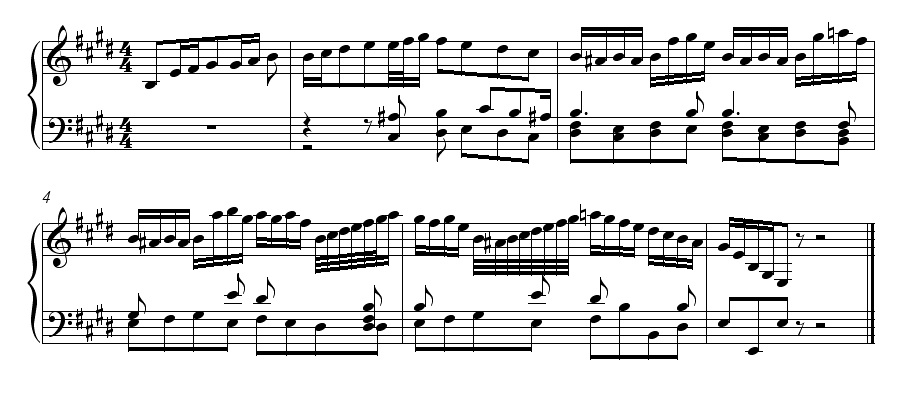

First up: regrets. I should have written down how I was feeling the other day, because it was really—really—good and somewhat intangible. I had had a long day of practicing, mostly the fugue from the “Hammerklavier,” which by the way is not very easy, and every so often I would glance out mournfully at the overcast weather. A humid hot day of storms was lingering into a second day; but somehow, mid-afternoon, the storms broke, the weather released itself and a boundary was crossed. Wind blew, the trees sprung into life. I walked down to the lake edge and pulled off my shoes and sat at the end of the dock looking at the light and swallowing the new air. Retrograde inversions forgotten.

The wind was coming at me. The lake’s waves were coming at me, a line of them, perpetually replaced, bringing a wonderful water-smell. The sun filtered through the surface of the water, creating what seemed to me an array of golden hexagons over the weedy bottom. These hexagons made me very happy, and I watched them wash out, melt, and reform. (This is nature, thinks the New Yorker; what have I traded away? what Faustian bargain have I made?)

It struck me, this oncoming. I sat for an hour, only partly soaking in the sun; mainly, I was breathing. Nature sweeping herself clean, breathing out … I reflexively, instinctively breathed in. Yes, this is exactly it, I thought, what music feels like when it is going well. Either it is water coming in, or water going out. The waves floating away, consequences of your actions, or the waves resupplying you with yourself.

At the end of Leon Kirchner’s wonderful Sonata No. 2 for Piano (which I played just last night, from which I may still be recovering), the final two pages are unquestionably waves going out, receding away. They are tremendously beautiful pages, partly because they only reluctantly! relinquish the energies and confusions of the preceding material. Yes, beauty, but … There is a terrible sadness, in some ways, to this outgoing; imagine, if you wish, the whole preceding part of the piece as a paddling, the creation of waves: and then, at last, the paddler stops and looks at his waves disperse. They are faint echoes of his desires. He watches. However!, in the final eight measures, the amazing Kirchnerian touch; he won’t quite give up (never gives up); a last inspiration seizes him, a last extended dominant 11th chord, in tremendous dotted rhythms, gestures spread across the keyboard, summoning registers, space … after this last wave there is nothing but silence.

But if in music these outgoing waves can lead to tremendous sadness, nostalgia, cessation, what do the incoming waves do? For some reason, just free associating on this idea, the first things that come to mind are certain retransitions in Mozart, certain magical dovetails, where the loss of one idea, the loss of the dominant tension, its relinquishing to the tonic, death of the development, nonetheless becomes a sort of refueling, a wave which turns around on itself and smiles. Not, for example, like the recap of the “Waldstein” Sonata (thrilling, glorious, virtuosic, triumphant), in which the return becomes a kind of fetish or climax, the crash of a wave upon the shore of the tonic; but the sorts of returns where we find ourselves traveling a new path without really even knowing it. And then the next things that come to mind are the wonderful first entrances of soloists in Bach concertos: those first, propagating inventions in which the instrument arrayed against the orchestra must define its own voice against the common ground of the ritornello … Always, I have thought, these opening moments in Bach concertos have a kind of iconic creativity to them, a self-rejuvenating energy, a joyful skid from thought to thought.

I’m sure readers of Think Denk must have their own ideas of outgoing and incoming wave moments in music.

As I said, I was very happy out there on the dock, breathing in. And later that night, I seriously had the option to write down some of my thoughts about it while it was still fresh … but instead (as so often), I turned on the TV. A newbie to satellite option orgies, I thumbed awestruck through seemingly thousands of channels before settling, amazingly, on “Ice Age: The Meltdown.” It seemed a saner choice than either “Ice Road Truckers” or “Special Victims Unit.” What drew me to “Ice Age” was not the humdrum main plot, but the subplot of a squirrel seeking an acorn. Simplicity itself. Oh, what travails the squirrel goes through to save its acorn, always again to be snatched away! I lay on the carpet and loved it, loved hIs love, his manic unceasing dedication (hmmm, relevance to musician’s life?). He defends his acorn, kung-fu style, from piranhas; he engages in animal trash talk with a hawkling; and finally, he seems to have the acorn in grasp, when a vast flood (“the meltdown”) overtakes him, endangering him and all the other characters. He climbs, bravely, an ice shelf, using the acorn as crampon (obsession as salvation), and is atop the ice shelf when the tiny acorn (illogically, wonderfully, Rabelaisian), wedged in the ice, forces open an enormous crack, splits the entire shelf in two… releasing pent-up flood waters, and saving the entire cast of boring main characters.

So the acorn subplot turns out to be quite pivotal, but in a totally nonsensical way, nice! The wonderful transcendence of the trivial. While the acorn’s symbolic resonance grows, the squirrel’s fate is unknown. As the main plo t clunked endward, I found myself wondering, ever more feverishly, what had happened to My Hero the squirrel? The movie makes us endure google-eyed, gag-inducing happily ever afters, ugh, but finally … We see the squirrel, staring up at golden acorn-crested gates, which open; he steps through them, finds acorns strewn liberally across pillowy clouds … Whoever wrote the music for this scene, I declare him or her a genius, one of the greatest living musical geniuses, and I refuse to back down from this; I want to commission an Acorn Heaven Sonata from whoever it is, immediately. But, having snatched up five or so of the innumerable acorns, he drops them all (fatal mistake?) upon seeing a giant golden Acorn in the distance, gleaming, glowing, colossal; the music becomes even more orgiastic; he prances across cloud-banks; it is a magnificent Love-Death of the Acorn …

t clunked endward, I found myself wondering, ever more feverishly, what had happened to My Hero the squirrel? The movie makes us endure google-eyed, gag-inducing happily ever afters, ugh, but finally … We see the squirrel, staring up at golden acorn-crested gates, which open; he steps through them, finds acorns strewn liberally across pillowy clouds … Whoever wrote the music for this scene, I declare him or her a genius, one of the greatest living musical geniuses, and I refuse to back down from this; I want to commission an Acorn Heaven Sonata from whoever it is, immediately. But, having snatched up five or so of the innumerable acorns, he drops them all (fatal mistake?) upon seeing a giant golden Acorn in the distance, gleaming, glowing, colossal; the music becomes even more orgiastic; he prances across cloud-banks; it is a magnificent Love-Death of the Acorn …

But of course, at the last moment, when he is about to hold Acorn Utopia, one of the main characters “saves” him, removes him from whatever reality-peril he was in; for a stunned, sad, frozen moment, awakened from his greatest joy, he looks around the real world, cannot believe the disconnect, this last, most devastating tease. He turns upon his rescuer, and for the foreseeable, illimitable future, as far as we can see towards the horizon of time, he is hounding reality.

I clicked the remote; the TV went dark; I crawled into bed, soothed; I slept deeply and remember no dreams.

8 Comments

The music for the scene of the heavenly acorn gates was written by Aram Khachaturian and comes from his ballet “Spartacus” (its original title is “Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia”).

I believe that with your fixation on the beauty of waves, you should come to the lovely state of Florida where they can be found in abundance. Especially in the Clearwater area. ^_^

It appears, Alessandra, that I have thereby declared Aram Khachaturian one of the greatest living musical geniuses. Hmmm. I knew I would come to regret that bit of bravado on the blog. Everything is contextual.

A fun coincidence: in the beginning of your Kirchner on Thursday night, a red squirrel was dancing up and down the pine tree outside the window behind you. It was when the music was still rather jolly, and it seemed very appropriate. The squirrel left, of course, when the music became more pensive… perhaps to contemplate its existence… or to find an acorn.

I enjoyed your playing and was bummed about the cut.

Funny coincidence upon a coincidence… There was a red squirrel running up and down the pine tree outside MY window today (though I was playing Mendelssohn, rather than Kirchner). Finally, out of desparation, the little furry maniac flung himself against my door. Wonder what the significance of this is…?

Whether Aram Khachaturian is living or not is contextual?

-S

Well, he lives on through his music, right?

Well, I think that there are true metaphors, but I guess I’ve never thought that ‘lives on through music/writing/etc’ was very apt. Can you really interact with a musical work? Of course, I’ve also had the experience of finding the lived-in nooks and crannies, the evidence of life, in a work left for the performer and listener, but this is like an archaeologist finding old letters to so and so, or the key left under the reed-mat for Aelfraed, and thinking it is for her. Aram’s works still enrich people, but if I needed to decide whether he was metaphorically dead or alive, I’d go with dead, because, for example, you’re not going to be able to commission an acorn heaven sonata from him, and nothing about his works is going to change, but rather people and culture change around them. Lack of change and growth is as dead as dead can be, I think. Tragic!

-S

… or a Spartacus Sonata, either. Too bad; it could have featured a music video with Kirk Douglas spliced in to play the piano for a few vignettes.

One Trackback

[…] Stars, Waves, Acorns […]