Courtesy a Japanese typhoon, traveling the Pacific to envelop me, I am becoming a connoisseur of the color gray and a certain unhappy look in a boy’s eye as he is looking through the window of a cafe. His glance like mine must rest on a brilliantly unattractive QFC sign. Floral, Deli, Espresso: it enumerates in navy blue Helvetica, against a yellow which only feebly disputes the clouded canvas of the sky.

Observant Seattle-ites may know by now that I have been spending delicious, self-consciously happy-sad time in Cafe Victrola, on 15th Avenue.

Ah, the beautiful people, ah, the many power outlets, sprouting laptops like electronic blossoms, ah, the pretense of no pretense, … the refusal to serve decaf! Snobbery through omission. And the rain dripping on hooded passersby only clinches it; the rain is a condensation of some futility floating in the air. Or an excuse to feel futile. I go to coffeeshops to stand in line, to await, to smile awkwardly at no one, to sip, to get jittery and dissatisfied; but mostly to watch people work. There, they talk with their laptops or study guides; their eyes are absorbed orbs; some people “have conversations,” “catch up,” but these exchanges are almost uniformly vacuous; it occurs to me that the joy of writing is that no one talks back. Clickclickclick says my computer keyboard, ahem … what do you mean no one?

I know I’m late to this party—like, really late, dude—but at nearby Sonic Boom, which I hear is a rather well-known Seattle record store, I went on a rather hilarious horizon-broadening spree and bought a whole bunch of stuff, including 69 Love Songs by the Magnetic Fields. The girl at the counter, when I read off my desires, looked classically askance. I was smitten. I suppose the term “Classical Music” finally began to feel stale in the back of my throat, like an unresolved stomach ailment, and then I just wanted to go in and swim where the taboos were, drown myself in what I never wanted. Overwrought, anyone? Rain makes me a bit dramatic!

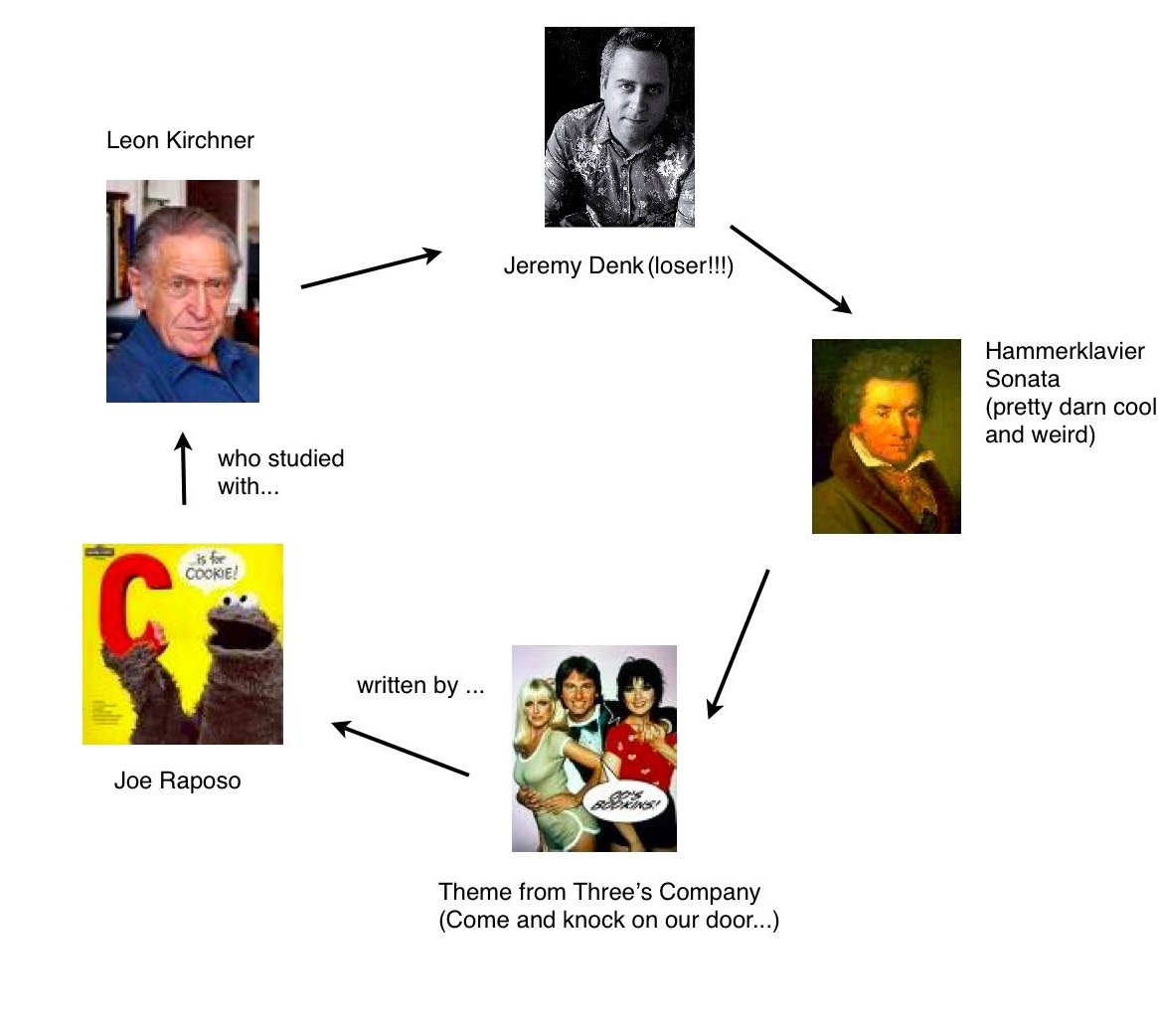

Classical music is so often the victim of a haughty love. Or a nerdy one. The other night, after a concert, I was talking with a young man whose enthusiasm was tremendous but whose every expression of this enthusiasm disheartened me in the extreme. He explained to me, smiling, all the reasons why he refers to the various Beethoven Sonatas in various ways … for instance, never “Les Adieux,” but always “Lebewohl,” since “THE goodbye,” he claimed, doesn’t make sense; “Waldstein” is permissible because it is a dedication; he confessed to using “Appassionata,” somewhat guiltily, but it’s OK because it’s Italian (?); but never, EVER, would he use the term “Moonlight” Sonata. I thought to myself, looking in his sincere, sweet eyes, aglow with these distinctions, that this person loves the same music I do, he’s my target audience, I can give something over to him, possibly, pass on some of my love … but at the same time this conversation about titles made me feel like jumping out the window. Probably I was reacting this way because I saw my teen self in his face … I sincerely hope he is not reading this blog entry, but if he is, what apology can I offer: I’m sorry you made me feel like jumping out the window???

Haughty love is worse than nerdy love, though, and it spreads through the apparatus of the classical world, sometimes through maestros pontificating and glorifying on PBS specials, sometimes through critics who adore to condescend, etc. etc. Everyone is guilty; I am terribly guilty; there are so many lurking clichés. All so well-intentioned, like a benevolent squadron of embalmers. So hard to speak of our music in the present tense!

Which is why, I guess, I went out to Sonic Boom and bought me some Magnetic Fields. I feel utterly incompetent to deal with this music, but I am humming it everywhere, now. The songs are alarmingly simple; they often simply repeat themselves, seemingly out of musical (never verbal) ideas after bar 16 or whatever; and yet, and yet (I feel) something is so RIGHT about them: the careful merging of the musical phrase structure and the rhymes, the subtle or not subtle reworking from verse to verse, of symbol, of syntax … They coalesce.

Or, if they don’t coalesce, they straddle strange contradictions. For instance, I am drawn to “Acoustic Guitar,” in volume 3. It’s not a  “serious” song. A short bit of guitar lead-in, a scale in medias res, a bit of vamp, then an awkwardly high voice is crooning (yes, that’s the best word?). The antagonism between the singer and the song is palpable. The singer is obviously singing to bring back a lover; but just as obviously it’s not going to work; he or she is taking it out on the guitar (threatening an inanimate object—“I’ll sell you if you don’t bring back my girl”); but the guitar’s just a stand-in, a projection of the inanity of the song itself, of guitar-playing serenaders, of desperate pathetic unrequited music-writing as a substitute, as a bubble in which the loser lives, finds inadequate comfort; truly the singer hates the very impasse he/she has been brought to, hates the very lyrical impulse itself, and yet … and yet … is singing.

“serious” song. A short bit of guitar lead-in, a scale in medias res, a bit of vamp, then an awkwardly high voice is crooning (yes, that’s the best word?). The antagonism between the singer and the song is palpable. The singer is obviously singing to bring back a lover; but just as obviously it’s not going to work; he or she is taking it out on the guitar (threatening an inanimate object—“I’ll sell you if you don’t bring back my girl”); but the guitar’s just a stand-in, a projection of the inanity of the song itself, of guitar-playing serenaders, of desperate pathetic unrequited music-writing as a substitute, as a bubble in which the loser lives, finds inadequate comfort; truly the singer hates the very impasse he/she has been brought to, hates the very lyrical impulse itself, and yet … and yet … is singing.

(Or at least that’s how I hear it. Let’s hope Stephin Merritt never reads this and comes after me for over-interpreting his stuff.)

I am smitten with 69 Love Songs for its element of mental play, both destructive and constructive; in much of volume 3, I feel, it’s telling you what’s wrong with the current musical world, pointing out the painful and obvious. It’s whipping the love song with one hand while worshiping it with the other; its obsessive rhymes veer between the incredibly touching and the absurd … The format is absurd, you seem to be reminded constantly; and yet the composer does not abandon it. The boy’s eyes looking out the cafe window seem to say “what is this crap world we live in?;” they critique what they see. Even in the act of perception.

There’s a canard in classical music talk … it goes something like this … the reason we can’t hear classical music as revolutionary any more is that all those dissonances and things have been explored, and we’re desensitized, we can’t really hear dissonance any more. As if dissonance were an addiction and we have maxed out on dopamine. All of classical music’s forced march to atonality, then, was a waste of time, requiring rehab.

I don’t believe Beethoven’s modernity lay in dissonance to begin with, or increased dynamic range, or more dramatic forms, or any of those things in particular. For a long time the equation dissonant-modern has been obsolete. Why, right now (which must, by definition, be p retty modern) we are surrounded by tremendously un-dissonant music … our culture is suffused with it. We are not “used” to dissonance. Hardly. Dissonance is as antiquated as a Ford Model T. So, how could dissonance ever have been the source of modernity?

retty modern) we are surrounded by tremendously un-dissonant music … our culture is suffused with it. We are not “used” to dissonance. Hardly. Dissonance is as antiquated as a Ford Model T. So, how could dissonance ever have been the source of modernity?

Dissonances can be eternally fresh if you sense the destructive forces they are about (and only then). Beethoven’s revolution cannot be stated easily, summarized (no more than you can summarize an entire grammar); it is not, as we have said, dissonance; it the destruction of a language written in the same language, upon which (nonetheless, paradoxically) the destructive act depends. The destruction has to be expressed in the terms of what is destroyed; something, perhaps, like a politically conscious teenager, whose leisure and wealth allow him time and opportunity to express the immorality of his leisure and wealth. It is the entirety of a language upending itself: quite a trick: like a person able to lift themselves off the ground. This is impossible; therefore, always partial; the ground always waits (the ground being perhaps, simply, the necessity of saying anything at all).

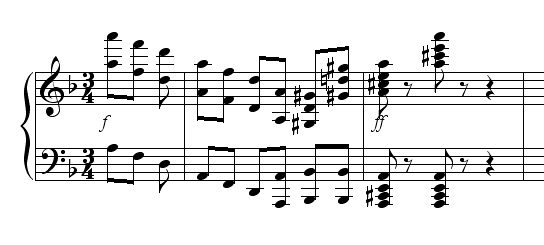

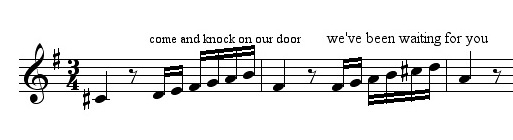

The Classical Style is boring, inhibiting, rife with annoying patterns and cliché; and yet Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven decided to take it for a ride, give it a go. They both created and destroyed it. They abandoned and fulfilled it (in that order). They knew more than adolescent rebels: it’s not transgression, it’s the quality of the transgression, how good the destruction feels, how much space it opens up. Things crashing into each other, collisions and conventions, the laughter of invention. What’s dangerous in the “Hammerklavier”: something that crosses a line, perpetually. In which direction it crosses is not relevant (past/future, major/minor, chaos/order, dissonance/consonance). The line becomes a string inside of you that is strummed … which is what you want out of life, to be strummed, right?

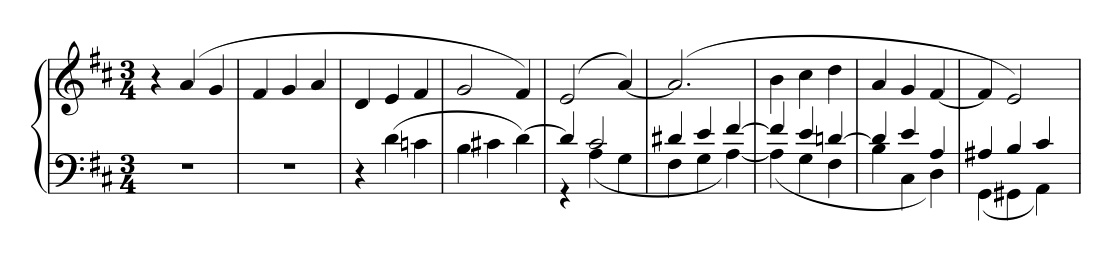

Admittedly, with all the rain and the dripping and the slick sidewalks I was beginning to get a bit too melancholy (overdosing on Seattle?), and was feeling decidedly unstrummed. But then, I was fetching a beer for Tom Bennett (our wonderful festival chef) and making a martini for host and friend Marty Greene and all this was taking place in a little back kitchen/bar they have at their house. Tom’s assistant, a very delightful lady, came in to dispose of some snacks … together we were clattering and rinsing, and in the next room a group was playing the slow movement of the Brahms Clarinet Quintet. I wasn’t expecting to love music, just then. But they were playing just that bit with these three notes …

… which those who know the piece will immediately recognize, and which reminded me at that moment very strongly of certain plaintive hooks in Merritt’s 69 Love Songs. They rubbed over those tones a few times. I hummed involuntarily as I shook the ice, gin, and vermouth … she caught me humming, and our teeth, grinningly uncovered by our mouths, stared at each other across the small room. “It’s so beautiful,” she said, sorting cheeses, and it didn’t seem haughty or nerdy at all, it was in fact unclouded, not dripping with the rain of pretense or any other emotional precipitation; it was shared, fragmentary, un-opinionated, unadvertised, private, real, imagined, communicated, received, loved.