One of the most curious, wonderful things about the “Concord” Sonata is the obsessive assault it mounts on Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Da-da-da-dum has become such an emblem, an audible logo, of classical music; the four notes express our whole tuxedoed, staid obsolescence, our desire to perpetuate ourselves (so they function, for instance, in a recent XM radio ad). Something about their sternness, their immediate minor-key attitude, the inescapable upbeat leading to downbeat, the timbre of the sustaining strings, full throttle … all of this captures perfectly the terminally uncool, that which in classical music takes itself too seriously, refuses to relax. (Don’t even get me started on Wagner.) Hierarchies, even patriarchies.

Was it possible for Ives to hear this work more freshly than we do now? Was it not yet such a victim of fame? Was it like hipster fashion before Urban Outfitters?

I don’t believe so; I think Ives picked it precisely for its cliché value (like he picked so many materials), and his reasons were complex. He is interested, apparently, in only the first four notes, in the germ; by the time Beethoven sequences it down for the second four notes, Ives is already bored by context, rhetoric, tonality’s rationalistic conventions. Bored, perhaps, by what Kundera would call the “spinning spiders” of filling in the space, of making sure the musical plot is continuous, not riddled with holes. (Ives loves meaning’s spread and leaps over gaps.)

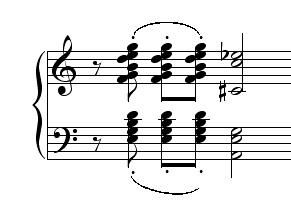

One could argue Ives chose this motive partly to rescue it: from its context, and from stifling respect. Did he foresee what would happen to it? In one of the most thrilling passages from “Emerson,” Ives reharmonizes the famous motive; he takes Beethoven, and dirties him up, with a glorious bluesy intensity:

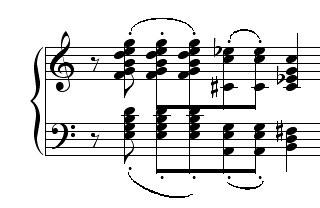

However wild, Ives’ rewriting is partly gestural analysis. Beethoven’s motive “wants” to fall by a third; that is what it does—fateful unstoppable descent—but the rest of the movement seems to try to fight this categorical imperative through counter-ascent, some sort of recoil or opposed force (sequence, agitation, struggle). So, Ives plays with this notion: he allows the motive, in the first rewriting, to go down yet another third:

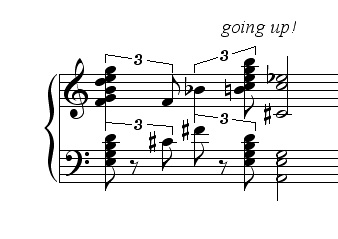

… which is like allowing the force to move past its target. And then, on Ives’ second “variation,” the motive reverses itself with a start, moving suddenly, surprisingly, up a third …

I love that leaping moment. One feels Beethoven’s idea—its third-ness—caged, growling, searching for a way out. In other words, the forces within it, its musical genes, are adaptable, fierce, looking for outlets in all sorts of directions; Ives paints a vector of raw musical force, freed from constraints, headed for the boundaries of the keyboard-world.

After you listen to Ives’ clustered version, try going back to the original! In these clustered chords, all the decorum of Classicism is stripped away, all the picayune perfection of selected notes. Ives manages somehow to make Beethoven sound harmonically unadventurous (not easy to do, illusory); but the raw energy of Beethoven’s notes is made more vivid. Though what Ives is doing is partly a distortion, a destruction, a mockery, at the same time it is something of an amplification, a homage: an act of devotion. You say to yourself: yes, that expresses something that Beethoven was after; Ives has expressed some “truth” about Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, by taking him, so to speak, to the cleaners. (He did not, however, sue Beethoven for 65 million bucks.) Don’t we lowly performers, when we try to play those elemental Beethoven motives, try to compress an immense amount of meaning into them, to express something besides, behind, over and above the plain girder-like notes? Try to sweep their connotations in under them? Ives knows our pain. And he explodes this wanted, connoted meaning into fantastic, variegated improvisation; having ripped the idea out of its context, he places it in all unlikeliest contexts, gives it all the most inappropriate meanings. Beethoven’s motto becomes anything at all. Though it first appears, in the opening cadenza, in rather typical, tautological (Beethovenian, heavy) bass interruptions, it eventually morphs into a million beings, a million Beethovens: light elfin interjections, blurry Debussyean echo-ramifications, gospel-like exhortations, and most paradoxically of all, at the end of “Emerson,” when it comes the last time, the idea (this idea! this paragon of the declarative motive!) becomes a murky, pianissimo, tonality-disturbing force in the bass, the final third descent adding one layer more of tonal ambiguity to the coda’s ever-descending spiral of untangling threads. A final whispered hmm. Though Beethoven’s opening notes appear to say “I’m here,” appear to state and affirm, Ives knows that for all their bluster they are also a question, that they hide some deeper unanswerable insecurity, the movement’s lifeblood.

When I began this post, I wrote “assault” but perhaps that was slightly overstating the case. Ives is not “attacking” Beethoven. Did Ives foresee our vast information age, with memes, ledes, semes and YouTube? Once Beethoven’s idea is allowed to float free, it adapts itself, becoming viral (just as it has in real life … though an impoverished, commercial virus which always represents the same tired thing). At the very least, Ives is against Beethoven’s motive as a symbol of the past: no, he writes, these notes are not Fate knocking at the door; they represent humanity knocking at the door of the future, or of the Divine … of that which might be, not that which is preordained, or circumscribed. (Classical music, he suggests, must never be circumscribed.) Ives’ “attack” on Beethoven is a symbol of a great affection, in the same way that your significant other is allowed to tease you about certain things that the wider world cannot.

It seems a silly simplification to say that Ives is advising Beethoven not to take himself so seriously (though that is part of it). Nor is he trying to redeem or deny the cliché. The motive stands—hackneyed, well-worn—and yet Ives tries to sail away to heaven on it. Lurking, hiding in this paradox somewhere is some of the essence of Ives’ language, his greatness, his unique contribution. It is this contradiction, this problematic question of tone, the conflation of the ridiculous and sublime, that makes it and will make it difficult (on top of the dissonance, of course) for many musicians and listeners to “get” or love Ives, especially as the question of tone somehow calls into the question the whole nature of the “classical piece.” Am I to take it seriously, in my plush red seat in Carnegie Hall? (If not, why did I buy my ticket?)

Luckily, there is a perfect symbol of this whole aesthetic problem lurking here at the Great Lakes Chamber Festival. We have a stage manager or coordinator or whatever, let’s call him X, who is utterly and wonderfully unfazed and umimpressed by any of us. He is roughly 17-19, I would guess… The other day, without any hesitation at all, while I was practicing, he nudged me off the piano bench, saying “want to see something sweet?” Displaced, I affirmed my desire to see something sweet. He explained to me that there is this song Claire de Lune by Debussy which is way hard in the key it was written in. Looking at me plain in the face, guileless, delighted, he showed me how he transposed it down a half-step to make it easier. “I don’t know how you would play it the other way,” he said. He demonstrated the simplified first three notes.

But X’s greatest moment so far in the festival, in my humble opinion, was at the intermission of a concert, when Paul Katz was telling him to make sure the lamp on stage was securely placed. This was a serious issue. As X listened, Paul began to tell the whole story: that the night before, he was in the middle of the Mendelssohn Trio when the lamp began to fall and somehow he had to hold up the music stand with one hand and keep playing and fix the lamp at the same time (I’m paraphrasing, I forget the exact details) … all to prevent the lamp falling on his priceless instrument, and to prevent the piece grinding to a halt. Paul stopped, waited for X’s apologetic response.

“Dude,” X said, “that’s f*&#ing hilarious.”

The look on Paul Katz’s face (cellist of the Cleveland Quartet, eminent and beloved musician, coach and inspiration to so many young musicians) … priceless. He said nothing at all, there were golden drops of befuddled silence. I left the area before anything could sully the moment.

Is this a good metaphor for Ives? I’m not sure. But I think it’s a funny story. Da da da dum.

9 Comments

Hilarious closer; keep analyzing Ives, it’s great!

The “Emerson” movement of the Concord Sonata has long been a favorite of mine. I love the way he uses the Beethoven motive combined with the hymn Ye Chrisian Heralds and with the Wagner “Wedding March” from Lohengrin. Have you heard the tape of Ives playing the movement and singing along raucously?

I enjoyed listening to the Ives you’ve provided on your site Jeremy. It’s kind of like watching an accident unfold right in front of you. You’re repulsed, yet you can’t look away.

Great essay. I love the Concord Sonata by my favorite movement would be The Alcotts.

i love anyone who has the balls to act like that around katz.

have you heard steve drury perform the concord?

It’s probably not all that &%$#ing hilarious to nearly have a blunt, metal object throttle one’s priceless 17th century instrument. Then again, the total irreverence displayed by your punky stage manager is kind of refreshing. It’s probably worthwhile to have someone around who doesn’t allow anyone to take himself too seriously.

Just wait until the Festival adult management reads this. Heh heh heh. Now I have a cocktail party tidbit for later in the week!

(reeeally late, but,)

Man, X was insane. It’s easier to transpose Clair de Lune than just play it!?

Hello ! I was searching for people that could have an interest for my music with the help of the name Charles Ives (one of my gods) and found your blog.

My new album is now available for sell, but it’s still without its first reviews. In the past, I have received incredible press from a variety of sources (All Music Guide, great composers…).

See and mostly listen by yourself some Philosophie Fantasmagorique.

http://www.critiquesdisques.com/vincent/music.htm

Thank you !

Vincent Bergeron

“In the course of a lifetime, one encounters very few major musical talents. Vincent Bergeron is one of those few, a unique composer who is at the forefront of musical thinking.”

Noah Creshevsky

Composer

Professor Emeritus, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York

Director Emeritus, Center for Computer Music at Brooklyn College