Where have I been? What has happened to me? To explain, I might just as well begin with a particularly terrible bowl of Spaghetti and Meatballs in Akron, Ohio.

It was my very first meal of a tour with Joshua Bell, a violinist you may have heard of. Now, a pianist has a function, which is to play too loud while waving his/her head around expressively.  And pasta has a function too: it’s supposed to serve as a canvas or frame for delicious sauce. But this flaccid frame simply refused to cooperate. It resented sharing its space. Nothing would stick to it. Therefore the sauce (which was not red, but a surly pinkish-brown) oozed forlornly about the corners of the takeout container, commenting wryly on the whiteness of its companion, as if to say “look, just look at what I have to deal with!,” and refusing to fulfill its remaining function, i.e., taste. Liquid flavorless recalcitrance! And the meatballs. As you gauged their mealiness in your mouth you felt you could count, like rings on trees, the number of times they had been frozen and irradiated.

And pasta has a function too: it’s supposed to serve as a canvas or frame for delicious sauce. But this flaccid frame simply refused to cooperate. It resented sharing its space. Nothing would stick to it. Therefore the sauce (which was not red, but a surly pinkish-brown) oozed forlornly about the corners of the takeout container, commenting wryly on the whiteness of its companion, as if to say “look, just look at what I have to deal with!,” and refusing to fulfill its remaining function, i.e., taste. Liquid flavorless recalcitrance! And the meatballs. As you gauged their mealiness in your mouth you felt you could count, like rings on trees, the number of times they had been frozen and irradiated.

Three different ingredients–sauce, pasta, meatball–and three different functions… How crucial that they act upon each other, how crucial that they profoundly communicate with one another!

I meditated painfully on this Threeness of Spaghetti and Meatballs in the cinderblock cage of my dressing room. It seemed a woeful injustice to begin the tour with such a terrible meal, and I’ll admit, I was still dwelling on it as I walked onstage, even as I sat down at the piano. I belched quietly into the pre-concert expectant silence … obviously, the three elements had not properly merged even in the accommodating cavern of my stomach. And so it happened–such is the power of fate!–that my mind was darkly attuned to failures of threesomes as Joshua and I began to play (for the first time) a work in … you guessed it … three profoundly interacting parts.

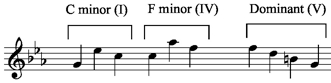

That no-name violinist played a melody:

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

And I played two separate streams of accompaniment, one in the right hand, one in the left:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The right hand is a river of sixteenth notes, a middleman … filling in the chord, “saucing” the melody. While the left hand, a slower stream of eighth notes, reveals a starchy bass-line. I couldn’t decide at the moment if the melody was the meatball; anyway, it didn’t seem central to my interpretation.

What defines the melody is partly the rocking, halting rhythm of the Siciliano: long and short notes in alternation. Also: the melody has a tendency to stop and start, to pause on pivot notes, before moving on. The two accompanying ingredients are utterly different: they do not halt or alternate; they are inexorable, they are continuous. Playing there onstage, in my peculiar food-furious state, I felt this as a kind of culinary contrast: the intermittent, impulsive melody set in relief against the knowing stream of harmony, like two different “philosophical flavors.”

There is no reason to mix pasta with sauce that won’t cling to it: it’s a category error, a basic mistake. There is (similarly) no reason to make melodies with arbitrary bass-lines; I mean, why write (tonal) music if the relation between your melody and your bass is going to be uninteresting? A lot of composers write music where the bass-lines ooze sorrowfully around the corners of their containers, looking reproachfully at the melody. A crucial element in musical composition is to create between these voices a clinging of some kind, some reluctance to let go, some salivation, some moment that lingers in the mouth.

The clinging of the melody to the bass is astoundingly beautiful in this piece (Bach BWV 1017). The melody is built more or less on a skeleton of chords …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

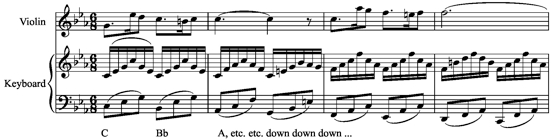

… It “likes” to arpeggiate through chords. But the bass has an opposed tendency: it wants to descend by step, in a long line, through the C minor scale …

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

This process–chords versus scales–is set in motion from the very beginning:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The melody outlines the chord of C minor, but even by the second beat the bass has moved on to B-flat. Superimpose B-flat on a C minor chord, and you get, of course:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

A wonderful chord, briefly glimpsed. This sonority, where a chord is “infected” with the next lower root, is (for me, for me!) the secret soul of this movement. Many of the chords in this Largo are haunted by this restlessness of their roots–while the melody clings to the past, the bass moves on. The resulting sevenths pop up throughout, dissonant beauties of passing. They keep appearing, persistently, but always briefly! They owe their existence to motion, to the tendency of the bass to descend, and therefore they don’t linger.

Bach, as chef, understands that if you take a melody tasting of triads and put it on top of a bass that descends linearly you get these particularly delicious sonorities. This is the reason he has put these ingredients together: to wring these beauties out of them. If you fail to taste them while you play, it’s your loss (and of course the audience’s).

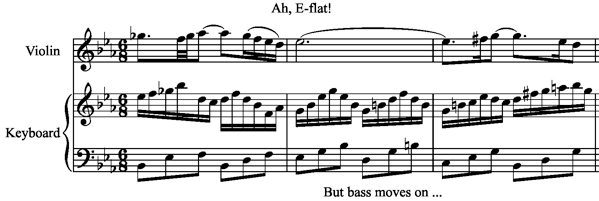

I will give you a favorite example. At one point the violin and keyboard decide they are going to cadence together on E-flat major …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… but it only lasts for one half of a measure, for one beat. The accompaniment immediately moves on: again, the bass has a thing for moving. The violin’s still playing E-flat, holding onto it, optimistically or stubbornly. The bass moves down to D: and so the keyboard plays the dominant of C minor against E-flat: a wonderful, grinding dissonance. [When people say they can’t stand “dissonant music,” of course you can tell them they’re idiots, they actually LOVE dissonant music, because without dissonance Bach (for example) would have nothing to say whatsoever.]

At the beginning of the measure, all three parts are in beautiful E-flat major. By the downbeat of the next measure, the E-flat has been “re-thought” as a part of C minor. But I like the beat in-between: when the E-flat doesn’t know yet that it has been rethought. Where the melody’s and harmony’s tendencies clash, where the parts diverge, you get a kind of blurred double image of past and future. If you agree with me that Bach is a particularly profound essayist in the nature of time, you might agree with this leap of assocation: that dissonant beat is the present. It is neither here nor there. In its in-between-ness, it is the most beautiful, tastable moment of all. Why is it always the moment you want to hold onto, that is passing by?

That’s why it sometimes seems to me that music theory is one of the most despicable disciplines there is, because you’d probably label the bass of that magical chord a “passing tone,” and once you’ve labeled it a passing tone it’s a bit deflating … doink!, it goes in the bin with all the other passing tones. Somewhat like passing through Trenton on your way to Philadelphia: unremarkable. In the same way, once you call something Spaghetti and Meatballs, it doesn’t necessarily follow that you’ve understood anything about pasta, or that you should serve it to paying customers, or why a pianist might eat such a ridiculous thing before a concert, or any of the related questions that might come up. But Bach had that way of using passing tones so that you could meditate on the passing-ness of things, what it is to pass, to move on, to leave beauties behind … of labeling the labels with meaning, breathing life back into the most basic, even the most unassuming, words.

Does this explain why I haven’t been blogging?

26 Comments

–> Does this explain why I haven’t been blogging?

Getting over your spaghetti indigestion? Touring with Mr. B?

In any event, I greatly appreciate your insights into music, you seem to have a good grasp of what makes good composition. So my question would be: Have you ever written any music? If so, and it were given the JD analysis, would it conform to the standards you are aware of? If not, please try to.

Thanks, and welcome back! Please don’t wait so long before your next post!

Oh, Jeremy, it’s so nice to have you back!

I just assumed you’d died.

I feel your pain over music theory. This is a classic case of how we got into analysis and how we need to get out of it (which I believe is stolen from the title of a paper by Joseph Kerman). As I see it, labeling a note as a passing tone is making a point about grammar. It’s like diagramming a sentence. It does say anything about what the sentence means. It just tells you that the sentence conforms to the rules of grammar, which may or may not be relevant to how you choose to read it.

Your own approach, on the other hand, flavored with references to Italian cuisine and driving on US 1, is making a point about rhetoric. I am not referring to all of the musical-rhetorical concepts that George Buelow explores in his New Grove article. Rather, I am trying to invoke the old Aristotelian notion of the persuasive qualities of rhetoric, persuasion in this case being pretty much directed at seizing and holding the attention of your audience, not that different from what Aristotle had in mind.

For several years I have been trying to flesh out the medieval trivium by also accounting for logic, along with both grammar and rhetoric, when I write about music. It started with writing about performance; but I suspect that it makes just as much sense to examine composition in terms of the same framework. I also believe that this approach fits Webern as well as it fits Bach. I suppose I do this out of the conviction that writing about “the music” without writing about how it is performed (not “should be” mind you but based on the hard data of actual performances I have experienced) will never be anything more than an idle exercise in the kind of music theory you so despise.

Anyone interested it taking me to task for my methods or how I have tried to apply them is welcome to visit my blog, which should be at the other end of the hyperlink on my name. I have created a “performance” label, which I try to hang on any exercise of these methods. I realize this is a blatant request for feedback, but how am I going to make any progress without it?

Meanwhile, I shall be happy to try to apply my methods to the next performance you give in San Francisco!

Well, it =has= been a while. Good thing that serenebabe gal — whoever she might be [hah] — tweeted about the post.

I want to assure you that GREAT PASTA does indeed exist in Northeast Ohio.

cheers!

You appeared eupeptic in Seattle. Thanks for the Ives!

Brilliant!!!!

Thanks

Sadly mediocre, reflux-provoking spaghetti and meatballs in Akron. Sigh. That image makes me want to cry crocodile tears into my ecstasy-inducing bowl of caramel-balsamic ice cream in Berkeley. Yup. It does.

I just started reading your blog, and I love it! I’m learning a lot about music from the combined scores and midi files that you post. The E-flat as a moment in the present that we’re trying to hold onto…wow.

Hey, Jeremy, check this out:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jh_1CKyZVSc&feature=related

When are you coming to Brazil? I know Joshua played here last year, but how about you?

Great post, btw.

This is a great piece! I really like how conveniently you incorporated the musical excerpts into your blog – it works really well.

As the Bible says so eloquently:

“And it came to pass . . .”

(The Good Book does not say, “And it came to stay.”)

Yay, you are back at the blog! Music theory aside (and that awful spaghetti, ugh) I trust you had a fine meal before (or perhaps after?) your fabulous performance at Walt Disney Concert Hall. That violinist guy was pretty good too. An injury kept me from your performance with the LA Chamber Orchestra this past weekend but in my head I can still hear your versions of Ives and Bach at Ojai last June. Looking forward to your stint as Ojai Festival Music Director!

dear Jeremy,

come over to my apt & hear those dissonances in a juicy baroque temperament and they’re really incredibly tasty…E-flat doesn’t function so well as a D#, so that long E-flat suspension is…oh so scrumptious. And the F# in the next bar – in the right hand – against the Bb in the bass…I mean, the E-flat against the B natural was so good, Bach couldn’t resist doing a little hint of it again. Bach without baroque temperament: it’s like unsalted pasta…

It’s good to have you blogging again. And playing. Brilliant analysis, too.

One of my favorite, similar moments occurs in Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony, 2nd movement, 2nd theme. The movement’s in E major, and he’s already playing with one’s expectations by setting the 2nd theme in c# minor. Gotta love Franz when he’s feeling into those 3rd relationships.

Anyhow. 1st clarinet comes in, and 6 bars into this plaintive little tune hits and holds a concert A natural, floating an octave above the syncopated string triads. So simple; so deceptive. The A natural is, at first, the third of a plain old IV chord in second inversion, until the cellos join in and allow the violas to reach up and grab a G natural, and suddenly it’s the root of a dominant 7th chord which resolves to its tonic in the next bar and for just a moment we’ve modulated, right there in front of God and everybody, from c# minor to D major. Don’t try this at home, kids.

Being Schubert, of course, that isn’t enough. The D major, in which the clarinet’s A is of course the 5th, lasts for almost a whole bar, but then the 2nd violins creep down to an F natural, nudging the violas and cellos to fall from D natural to D flat and thence to C natural as we cross the bar line, and suddenly the A becomes the 3rd of an F major chord. It’s like the sun peeking out from behind a cloud. It isn’t exactly a dissonance that gets us there, it’s a “passing” augmented triad which only lasts a 16th note, but in that instant we have really no idea where he’s taking us, and meanwhile the clarinet is serenely insisting that if we just believe him, everything will be all right in a second. And, of course, it is, and sublimely so.

I, personally, love the fact that it’s the violas who get to instigate both of those stunning transformations; insert your own viola joke here, if you like.

Love the blog, especially loved the Brahms post.

Yesyesyesyesyesyesyesyessssssss!!!!!!!!!!! Thank you, Mr. Denk, so very much for keeping us updated! I could not feel more thrilled and ecstatic right now. I’ve been religiously checking your blog, and finally it is so nice to have you back again. Don’t spend too much time contemplating over your meatballs now! 🙂 I have yet to hear you perform with Joshua Bell live – it must be one of the most incredible experiences life offers. Two of the most amazing, extremely musical, and passionate musicians the world is lucky to have.!

Hmm. So that’s what music theory is. Labeling. huh. Hooda thunk it?

I suppose that if you had had the good sense to eat the spaghetti in Trenton instead of some ghastly place like Akron (Italian food? Ohio? Yep, that’s the first place that comes to mind for it) there would have been one fewer blog posts in the universe.

I’m not even sure how I stumbled across this website at this point, but by golly, this is what discussions about music should be like. Crazy metaphors, irreverent humor, insults flung at both music theory and NJ in a single paragraph, and wisdom to boot.

Perhaps it is as they say, that “you can take the pianist out of Oberlin, but you can’t take the Oberlin out of the pianist”.

Impressive work; I’ll enjoy checking back in from time to time.

there was something about your blog in your bio for the Carnegie Hall concert, and i wondered why you didn’t update if you were inviting new readers. understandable though. good head-waving, by the way.

Thankyou so much for this inviting blog: inviting into music theory, of which I know nothing, but coming to it as a physicist…I wonder about your ‘beat-in-between’, a moment that must transcend precisely because it cannot be structured as belonging to one key. The source of my doubt is that your violinist, if my ear can be trusted, makes in the middle of that bar a minute adjustment of pitch that, so to speak, makes up the E-flat’s mind for it: in other words, faced with a choice of two contexts, before and after, this performer has put his eggs in the latter basket (marking a second transition at the end of the samebar more with a gesture of emphasis in the bowing than with pitch). Indeed: if the dissonant beat is ‘neither here nor there,’ how is the string player to act? It would be sacrilege, I suppose, and ahistorical, in performance to sacrifice the continuity of that long E-flat?

I guess this is one of the reasons that jazz musicians,especially bass players, tend to love Bach. Beautiful, mysterious harmonies floating about. Thanks for making music theory what it is supposed to be, illuminating and inspiring. Debbie AKA Bassbabe

As you can imagine from my name, I LOVE music theory. I teach it at the college level, and it’s my passion. Two things about this blog struck me: 1. how right you are about the deficiencies of our analytical system – labels can be quite subversive – and I, too, am guilty of telling my first-year students who are confronting their first analysis example that “you don’t need to worry about that – it’s a non-chord tone.” I’ll think long and hard before I say that again! 2. your erudition and eloquence shine through every sentence in this blog, but I dare say that you wouldn’t have the vocabulary to describe what’s happening if it hadn’t been for some theory teacher somewhere teaching it to you, so you’re actually, if unwittingly, a sterling example of the benefits of studying music theory! Thank you for your insights, I’ll be sharing this blog with my students, and I hope to see you perform someday!

Jeremy–for fun, would you please go to this site, scroll down exactly five times, and say Boo to yourself.

http://www.classical-composers.org/comp/mozartwa

This is what I love so much about Bach Double Violin Concerto 2nd mvmt, particularly the opening. I purposely ask to play Violino 2 part because of this exquisite conceit!

I love your blog!

3 Trackbacks

[…] meaning, breathing life back into the most basic, even the most unassuming, words.” —Jeremy Denk […]

[…] found the following passage taken from Jeremy Denk’s writing on Bach to be particularly thought provoking. My background as a violinist continuously seems to infiltrate […]

[…] pianist tells me his tongue is planted firmly in cheek. Well, that and a blog post entitled Joshua Bell tour Trauma: Meatball Edition. He recently subbed for an ailing Maurizio Pollini on the Stern Auditorium/Perlman Stage of […]