I’m not saying I want to be understood, or claiming it’s worthwhile either. It seems to me understanding me is one of the most boring things to do with me, or to me. But! … if someone wanted to understand me this parable is probably key:

THE PARABLE. I am lying on the beach in South Beach, on a glittering cloudless day. A coolish ocean unrolls gentle waves diagonally against the sand. Scurrying attendants fetch towels, drinks, snacks, and beautiful, beautiful people walk by in the prime of their lives, acting like perfectly cooked steaks in the steakhouse of life. Similarly greased, plated. I appreciate them!, but dourly remind myself that they are “just” bodies.

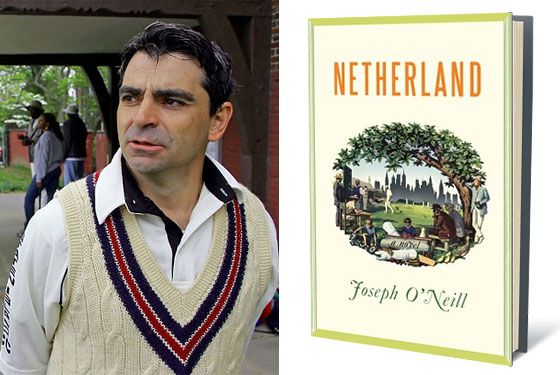

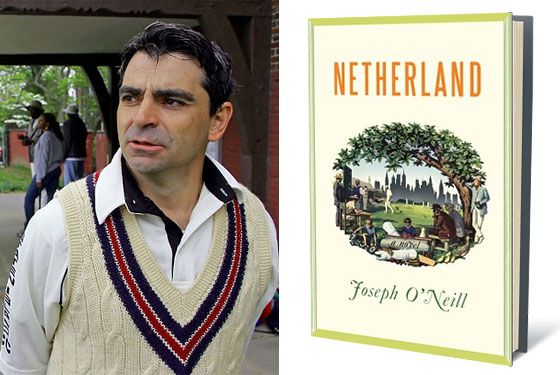

I begin to read a book entitled Netherland. I begin to dislike it. But the more I hate it the more I continue to read it, the more determined I am to finish it. I sigh and E laughs and I sigh and sigh, then I moan and say “get over yourself”–talking to the writer who is not there except in form of his book!–and E just looks at me and asks why am I still reading and I just continue to read and read, as if entranced.

Then we swim, E and I. The water is perfect and one could spend the whole day there in the salt water only a few feet deep, swimming from one small goal to another. I love the water—my being relaxes into more being—but even as I love where I am, I feel the riptide of the book. Soon am back in chair, a smaller being, reading the hated book. A woman in front of me is really “doing the beach”; she is drinking Coronas aplenty and talking to some handsome men she just met and describing that whoa she was so wasted she thought but then in Vegas maybe more wasted etc. etc. I disdain her. I think I am better than her, reading this book that I hate. I look around at the lovely world, then I keep going back to the book. I think about the lovely world while I am reading the book, why the world is vastly better than the book, but I keep reading the book. END OF PARABLE.

Several days later, I was on the NY Times site and I was surprised to read that the author of Netherland …

… seems incapable of composing a boring sentence or thinking an uninteresting thought…

But I present to you:

But mostly the diners were cricket men and their women—players and officers of the American Cricket League, the Bangladeshi Cricket League, the Brooklyn Cricket League, the Commonwealth Cricket League, the Eastern American Cricket Association, and the Nassau New York Cricket League; of the New York Cricket League, the STAR Cricket League, the New Jersey Cricket League, the Garden State Cricket League, and the Washington Cricket League; of the Connecticut Cricket League and the Massachusetts State Cricket League; of my very own New York Metropolitan and District Cricket Association; and, by particular invitation, Mr. Chuck Ramkissoon, whose guest I was.

—Netherland, p. 136

… a sentence so stupefyingly boring that I fell asleep three times while typing it into my computer and had to wipe the drool thrice lovingly off my mousepad. Not only is Joseph O’Neill capable of a boring sentence; he is one of the most gifted writers of boring sentences in the last decade. Example 2:

Considered, too, was the depth and density of grass roots and the crucial disproportionality of a blade of millimeters-high wicket grass traveling six inches underground, and of course we talked of the constant battle to defeat moss and bluegrass and clover and the other weeds.

I might enjoy this sentence more if it didn’t begin with “considered, too”? But with apologies to all the intelligent and perceptive critics and civilians who have loved this book, I really am flabbergasted, flummoxed! What has happened here? I would like to settle on the convenient thesis that I am right and everyone else is an idiot, but I am also generously willing to consider the possibility that all these happy critics were the victim of some simultaneous hallucinogenic attack brought on by the collapse of Lehman Brothers. Compared to GATSBY? Really?

The main theme of Netherland seems to be the moroseness of its narrator. The author, perhaps fearing understatement, really piles it on! For example he’s walking down the staircase of the Chelsea Hotel:

I found myself freshly eyeing the pipes and wires and alarm boxes … These tokens of calamity and fire, taken in conjunction with the fiery and calamitous art, gave a hellishly subterraneous aspect to our downward journey … and I was almost startled when we reached the bottom of the stairs not to run into chuckling old Lucifer himself …

When I walked those Chelsea Hotel stairs, the pipes didn’t Satanically manifest. Maybe I wasn’t writing a post-9/11 novel? I understand all this fear of pipes plays wonderfully into the theme of post-9/11 impending disaster everywhere. But maybe “fiery,” “calamitous,” “hellishly,” “subterraneous,” “downward,” “calamity,” “fire,” “bottom,” “Lucifer” could be a bit over the top? And if you think this narrator gets spooked going down the stairs, well buckle your seatbelts:

The low ceiling was supported by an extraordinary clutter of columns; so many, in fact, that I could not avoid the perverse impression that the room was in danger of collapsing. An enormous counter ran around three quarters of the office like a fortification, and behind it, visible between crenellations made by partitions and computer terminals, were the DMV employees. Two of them, women in their thirties, screamed with laughter by a photocopying machine; but as soon as they reached their positions at the counter they wore faces of sullen hostility. One could understand why, for assembled before them was a perpetually reinforced enemy, its troops massing relentlessly on the hard pewlike benches. Many of those seated were hunched forward with hands clasped and heads bowed, raising their eyes only to follow the stupendous figures … that randomly appeared on screens with the purpose, never achieved, of moderating the agony of suspense in which visitors were placed.

Oh, come on. “Agony of suspense”? With penetrating novelistic insight, O’Neill reveals that it’s not really very fun to go to the DMV. Does anyone else find the use of the word “crenellations” pretentious? (Raise your hands.) O’Neill’s technique seems to be: 1) find a metaphor, the more obvious the better; 2) find every possible modifier that goes along with that metaphor (fortifications, hostility, enemy, troops, reinforced, massing, egad!); 3) move on to another exaggerated metaphor. Hey, the book writes itself!

As I was reading this passage, particularly, I began to feel I’ve read this before, but much much better, and very soon it hit me: the passage at the beginning of Austerlitz, where the narrator visits the formerly SS-occupied fort of Breendonk, which  he has studied in diagrams, and now encounters in reality:

he has studied in diagrams, and now encounters in reality:

… I still had an image in my head of a star-shaped bastion with walls towering above a precise geometrical ground plan, but what I now saw before me was a low-built concrete mass, rounded at all its outer edges and giving the gruesome impression of something hunched and misshapen: the broad back of a monster, I thought, risen from this Flemish soil like a whale from the deep … the longer I looked at it, the more often it forced me, as I felt, to lower my eyes, the less comprehensible it seemed to become. Covered in places by open ulcers with the raw crushed stone erupting from them, encrusted by guano-like dropping and calcareous streaks, the fort was a monolithic, monstrous incarnation of ugliness and blind violence …

… it was only a few years later that I read Jean Amery’s description of the dreadful physical closeness between torturers and their victims, and of the tortures he himself suffered in Breendonk when he was hoisted aloft by his hands, tied behind his back, so that with a crack and a splintering sound which, as he says, he had not yet forgotten when he came to write his account, his arms dislocated from the sockets in his shoulder joints, and he was left dangling as they were wrenched up behind him and twisted together above his head …

I realize that misery is not a competition, but why does Sebald’s writing make me feel he’s “deserved” his melancholy more? Poor multimillionaire Hans, aww, had a bad day at the DMV. Jean Amery had a slightly worse day, and Sebald’s plain “sound which … he had not yet forgotten” is so much more powerful than O’Neill’s metaphoric noise.

Maybe it’s endemic to our modern world that we’re all looking for something to be miserable about, some way to replicate and endure the terrible cataclysms of the past–as if that would “prove” us, our existence, as opposed to all the pixels and megabytes we consume–though all around us even worse cataclysms hover. The gratuitous cultivation of sorrow, which devalues real sorrow? It seems to me a shame with all the real menace in the world these days, that Joseph O’Neill must resort to exploiting metaphors for more tragedy, so ham-handedly, so post-modernish, e.g. this parade scene:

… I turned around just in time to see Ronald McDonald veering away and crashing into the barriers. There were screams. A man in a doughnut costume was knocked over …

It’s true, this unending self-pity annoys me, but I’d forgive it if the book had aesthetic virtues: for instance, some sort of shape, form, some barely discernible vector. This is why the Gatsby analogy mystifies me. I have never read a more aimless mess of a novel, ever. Is Netherland about Hans and his wife, a barely-sketched relationship, or Hans and his child, used as an endearing prop, or his shady friend Chuck, or is it about the man who dresses as an angel in the Chelsea Hotel? Luckily, our narrator lives there, where he can meet all sorts of quirky New York characters whom he can saddle with Symbolic Garbage, while he’s slouching from subject to subject. At some point of course he saves the angel from jumping off the building, and buys him some clean wings at a sex shop. High school essay writers, sharpen your symbolism-loving pencils! And if you like symbolism:

… life carries a taint of aftermath. [editor’s note: YICK]. This last-mentioned word, somebody once told me, refers literally to a second mowing of grass in the same season. You might say … that New York City insists on memory’s repetitive mower—-on the sort of purposeful postmortem that has the effect, so one is told and forlornly hopes, of cutting the grassy past to manageable proportions. For it keeps growing back, of course.

Ah, I see now!, I see clearly, mowing is a metaphor for memory and so all the ensuing tedious discussions of grass are symbolically necessary, whew!, thanks for explaining that to me. (The author should NEVER explain his symbols, hello???) Harrowingly, Gatsby drives to its doom through a series of ineluctable events; Netherland oozes and whines through a series of unavoidable cricket matches. Some unnamed critic opines that Netherland’s prose “glows”? Agh. Well, to conclude this rant, I give you this incandescent morsel:

By the standards I brought to it, Walker Park was a very poor place for cricket. The playing area was, and I am sure still is, half the size of a regulation cricket field. The outfield is uneven and always overgrown, even when cut … and whereas proper cricket, as some might call it, is played on a grass wicket, the pitch at Walker Park is made of clay, not turf …

…. zzzzzzzzzzzz. I rest my case. Maybe it glows when you turn your computer screen’s brightness all the way up? I welcome your offended comments.