I headed to the Y, alone, to “get my Schumann on.” I got marooned in the middle of row O: singles limbo. Sorry, stumbling over knees, squeezing, sorry, saying good thing I didn’t have dinner yuk yuk, thinking, don’t give me that sour look, lady.

Applause, applause.

After a bit, I noticed the woman on my left was reading a book; her posture was scarily, Classically erect. But meanwhile the elderly gentleman on my right had surrendered to a slouching, abundantly Romantic snore. I was torn between them.

The man’s snore wasn’t regular, but wasn’t quite capricious, either. It was too lazy for whims. All the while Steven Isserlis and Denes Varjon were playing Schumann intensely, with incisive rhythm the snore ignored, and though my thoughts were a mess of broken threads from my two weeks home–extraordinary weeks and at the same time terrifyingly typical–every so often a SchumannMoment™ arrived which commanded, compelled, commandeered my brain, saying: stop, madman! The music of a madman a vaccine against mild madness. I had the feeling RS grabbed thoughts right out of my brain and hugged them to keep them from fidgeting. Under the unbearable stare of those musical moments I felt I was a burger (or any cut of meat, anything which requires tenderness) which had been placed on a hot surface, seared by the notes: I was sizzling on those moments, all my juices welling up, but sealed inside.

One moment like this: the fourth movement of the Märchenbilder.

Schumann may not be so much a composer of pieces as he is of visions, visions breaking through obscurity–as opposed to Mendelssohn’s clarity–and this heartbreaking vision is of a lullaby. Schumann does not simply express something through the medium of a genre; he’s not content just to fill the vessel; he does not write “a lullaby”; he writes into the lullaby. He writes music–how do I put this?–about the cluster of emotions surrounding a lullaby.

What’s a lullaby about? What does it do? Ridiculous answer: it lulls. More serious answer: it attempts a paradox: to create stillness through motion. This is usually rocking motion: the pendulum of the crib, the swing of two swaddling arms. This sort of motion slash non-motion is one of the musical “topics” of the lullaby. It leads us (ideally) to suspension, a sacred space beyond time.

But there is another “topic” to the lullaby, quite haunted by time: the act of relinquishing to sleep, and associated loss. The sadness of day turning into night, the slipping-away of the experience of the day, letting go into non-being. Therefore lullabies are visited by melancholy, farewell, a sense of the day’s events vanishing, life vanishing … (sleep as a small death, a rehearsal for death … ?)

And there is a third “topic area”: the tenderness of the person singing, the love of the lullaby-er for he or she who sleeps. Roland Barthes has the money quote on this:

Besides intercourse … there is that other embrace, which is a motionless cradling: we are enchanted, bewitched: we are in the realm of sleep, without sleeping … this is the moment for telling stories … Yet, within this infantile embrace, the genital unfailingly appears … the logic of desire begins to function, the will-to-possess returns, the adult is superimposed upon the child. (A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments)

Maybe the ideal lullaby is parent-to-child; it is not erotic, at all. But the lullaby is not confined by this. It takes place in bed, and can also be the indulgence of lovers: to lull someone to sleep is an unselfish act of love, a cipher of trust, of intimacy.

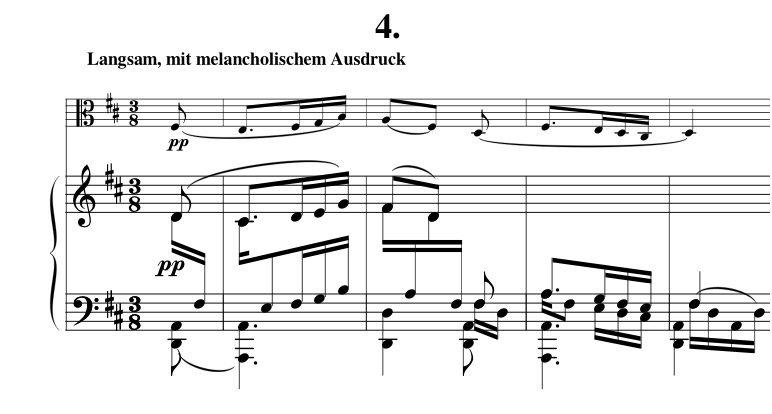

And in this short, almost throwaway masterpiece, Schumann ranges through these three topics, with a poet’s control of this semantic world. (He loves the confluence of adult and child.) He begins with Ideal Lullaby, a sacred space for sleep:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

And what’s genius here is what’s not. Absence of certain things, presence of simplicity. No harmonic complexity, no accidentals; the bars rock back and forth from five to one to five to one. And the melody a kind of written-out redundancy, filled with doublings, echos. Watch the viola go from F# to A, then watch the piano go from A to F# … and the complement (a hidden phrase, spooning with the first!) … the piano playing a melody around D, then the viola playing a melody around D. These two strands are interlaced, interlocking, doubled at the sixth or at the third …

… and with this, the piece seems to reach out to the wider world and grab at the waltz, at some “Viennese sound,” with its bittersweet flavor; it grabs its associations, or just a fraction of them (loss, love, dances of the past), and recedes into itself. Because, of course, the phrase doesn’t go anywhere.

You could say so much more; you could really go nuts free associating on these two voices doubled, at interchangeable intervals … Is it someone singing, and someone else harmonizing?; a voice and a hum?; is it the voice of a person and the echo of their voice in the nascent dreams of the person who is falling asleep?; is it about the two people falling asleep and their intertwined selves? There is no reason to decide; Schumann activates them all.

Phrase 2 begins like the first, lops on a different ending:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… these two bars (ingenious, haunting, pivoting bars) take us slightly out of our sleepy space. Perhaps it is “merely” the bass which does this, shifting down from D to C#. But that’s what’s wonderful about music, sometimes–one bass note moving can mean a new world. In this case, Schumann tiptoes out of the world he has set up, bridges us into a more overt melancholy:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

So soon, we have left the cocoon! This third phrase’s world is definitively Not-D-Major: it begins and ends in e minor (it breathes e minor). At the same time the texture changes; the viola and piano are no longer playing in thirds or sixths, but gel into a plaintive unison. How do I express this: on the one hand the lush D major phrase, pianissimo, with three blurred voices, enmeshing; and now the E minor phrase, sadder, more pointed, more inflected, focused into a penetrating unity … Why? Because, for Schumann, the peacefulness of the first phrase (dream) and the melancholy of this third phrase (reality) are inseparable; they follow upon each other absolutely, they depend upon each other. They are the cause-and-effect in a logic of emotion, the resonances of a single poetic image.

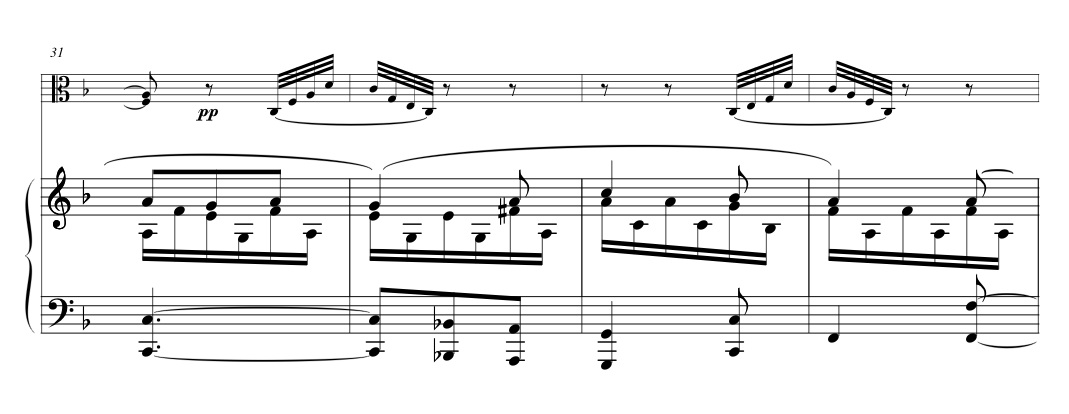

I would like to notice one more thing before moving on. Monotony’s a virtue for a lullaby. So, watch this third phrase go from B to F# to G, then backwards from G to F# to B, then back forwards again B F# G:

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… a beautiful variation on reiteration. This sort of thing’s all over this piece: Schumann hovering meaningfully around a few notes, only partly hiding the monotony. In other words, each phrase is a kind of act of limitation, of concentration, of choosing; the lullaby is the creation of a hallowed, peaceful space; each phrase, too, is a kind of creation of a single space; finding a fulcrum to swing on, rocking around it, then rocking into another space …

I would love to delve into and narrate the whole piece, bit by bit, but let’s skip ahead to the moment where the bass pulls a trick on us, and we slip into F major: the middle section. F major! F major is a brand-new space. And remember, the piece has been about various spaces, delineating them, rocking within them … We have slid into yet another; but this is the last one we shall find, this is the last curtain to draw aside:

For some reason, many violists tend to get confused here. Perhaps they can’t come to grips with the fact that they are no longer the melody, a common string player problem. (Don’t tell Josh I said that!) They put in all sorts of rubati and expressive thing-a-ma-jiggies (yes, that’s the technical term). Particularly, they do things to call attention to themselves, to get in with the world of the piano’s music. Maybe this is a good chamber music urge; but in this case a good urge might be terrible! Remember that in the opening, the viola and piano are deliberately doing interchangeable phrases, coming in and out of the foreground, exchanging voices … as if they were one inextricable thing (two lovers, a voice and its echo, etc. etc.) But here, it is utterly clear that the viola and piano have gone their separate ways: the piano throws forth a long-breathed, sustained melody, and the viola comments with pianissimo rustles. There are no hairpins on these rustles, no tenutos, no indications of any kind …

If you imagine the process of a lullaby as gradually increasing sleepiness, as the gradual retreat into a dream, this F major is our farthest, stillest, most dreamlike place. And at that stillest place, another layer awakens, which the viola’s rustle: is it a breeze in the room, is it the dreamer’s faint consciousness of the lullaby past, is it some sort of rocking reminder of normal time wandering into the world of sleep? Or the pianist is awake, and the violist is asleep, faintly snoring. You decide, again; all of these things are possible; Schumann merely sketches out for you, at the center of his tone-picture, the contrary motion of the two instruments: the piano towards melody and continuity; the viola towards rocking, breathing, intermittency.

There is an extraordinary thing about this piano melody here at the center, the eye of the lullaby. Notice that the first phrase …

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… ends with three notes, C Bb A. The second phrase begins differently …

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… but comes around to the same three notes, C Bb A. Though there is the appearance of two if/then phrases, the “then” is always the same. Music is so great at these dead-end streets, at decorating these obsessions. No matter how you begin, you end up there, gazing at C Bb A…

Then comes (for me) the Schumann Moment of Moments, a sudden eruption:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

I was holding onto my seat at the Y, I was overcome; even the snore faded into the background. Where have these triplets come from, why are they surging into the world of the lullaby? And they keep heading to these supercharged harmonies, returning to sensitive points, charged with tenderness, filled with yearning.

This is where Schumann completes his poetic “account” of the lullaby: here, with the emergence of Romantic Love. Behind the nurturing sleep and comforting dream, some truth emerges, some un-repressable emotion (which cannot be stilled, cannot be lulled). There is something frankly passionate here, something physical, visceral: the opposite of the lullaby, and yet its emotional core. Out of the stillness, out of the void described in part by the viola’s reticence, in part by the limited range of the piano melody, in part by the new “holy” key of F major–out of and into this stillness comes this tremendous current, this beating heart. Seemingly it’s a new voice, this triplet voice, but notice …

![]()

… this phrase, like the previous two, culminates in C Bb A… (the fixation, the obsession …) This phrase, for all its passion, is absolutely connected to the earlier phrases, is part of the same predetermined stream: a meeting point for the intimate sharing of sleep and for the awakening of desire.

Schumann distilled Romanticism into flashes of insight; he insists that we understand the outburst and the stillness at once, as one and the same irreconcilable thing. Though music unfolds in time, note after note, its effect is often this kind of black hole, where the gravity of the conception draws together all the materials in a unity, in a single epiphany. Schumann’s such a great composer of flashes, of little sparks of imagination, connecting one thing to the next, often tenuously. But what’s even more astonishing, to me anyway, is the completeness of his understanding of the thing, however complex, he wishes to create or evoke. How much thought about the lullaby can you compress into these three pages of music? You have no idea … He’ll tell it all, he’ll build a cosmos out of tenuous flashes.

I have one last thing to say, related but not entirely. At the crucial moments I have just obsessed about, especially those repeated C-Bb-As, I have an uncanny feeling, as though I am being watched, subjected to a penetrating gaze. Yes, I thought later, safely at home eating my spicy chickpeas, avoiding the piano, looking at my grimy reflection in the nighttime window, some Schumann moments, it seems like he’s staring at you the whole time. He never lets this gaze drop, while the notes pass by. Or maybe there’s something else, slightly scarier, like: Schumann knows me? Not only is he staring at you, but the stare implies an uncomfortable understanding. Amid all the people in the hall, who peel away like movie extras, he is speaking only to you.

10 Comments

the music of a madman

suspension, a sacred space beyond time

a penetrating gaze

C Bb A

I’ll come back again and again to read this as a lullaby

but first, suddenly, I’m hungry !!!

I need to read this several more times. You had me at “the cluster of emotions surrounding a lullaby.”

I grew up down the street from the Colorado Philharmonic, now the National Repertory Orchestra. I spent my early teenage summers in the company of college-age musicians, who would occasionally share insights like this.

I miss that.

I love it,

and your playing of Beethoven and Ives at the DSO inspired me greatly.

Thanks

Thanks for your insights; I think Schumann might be overlooked (by me). Do you have any other recommendations as to what to listen to to get into his head? Or, perhaps, to allow him to get into my head?

Also, more music samples: those are wonderful. 😀

What marvelous writing about music! Who wouldn’t jump at the chance to hear Schumann after reading it? Your ability to translate feelings and musical events to words may be an even rarer gift than great musicianship; thank goodness you have this platform. If only newspapers had carried more of this and less dry dissection, perhaps both fields would have broader reach.

I’ve never heard this piece before, thank you.

I too have had a few SchumannMoments myself – I

know what you mean. I really don’t understand

how people are bored by his music.

I’ve felt something similar in Schumann. Not that he knows me, but that he is very knowing, and has great capacity to know. That if he encountered me, he would indeed know me, fully, that I could hide nothing. But a preoccupied indifference in him keeps it from happening.

Love your blog! This is fantastic writing, and I hope to see lots more to come.

This is amazing. I must ask a newbie question, though: what is the title of this piece? I want to go hear it….

Oops, I just read the blog more carefully, and saw that it’s the fourth movement of the Märchenbilder. 🙂

One Trackback

[…] of them, music lovers today solidly rank Schumann among their top desert island composers. In his blog on the greatness of Schumann , pianist Jeremy Denk describes his ‘Schumann moments,’ occasions when he senses, via the […]