I fled Twitter. It was a depressing stream of people saying how wonderful their last concert was, that they just loved playing with so-and-so, etc. etc. It’s not that I don’t want people to be happy, I’m just allergic to the eternal electronic happy-face. At times, I’ve overcompensated with meditations on misery–which is taking the other easy way out. But, I suppose I have a rationale: first drain the glamour of the musician’s life, dim the halo, then let the glamour of the “music itself” shine forth!

Hypocritically however, I just can’ t help gloating what a fantastic, splendiferous week I had playing Mozart with the St. Louis Symphony led by Nic McGegan. I loved it, loved them. They played with such openness and elation: that’s what certain Mozart tuttis are about, don’t you think, a kind of elation, celebrating the appearance or resurgence of the themes? (The pianist finishes a cadential figure, trilling, and the orchestra chimes in: yes yes, all that and more.) A very short and smiley violinist from the orchestra said, “It’s all about the possibilities of C major, what C major means” and she was so right: the thrilling ascending sequences, the crunch of certain intervals, little bumps but a lot of things that are just plain, standing in front of you, in other words no “black keys” of complication.

She and I geeked out about Mozart, blissfully, over a basket of homemade potato chips with a pot of beer and cheddar sauce which my doctor would sincerely prefer I not eat.

In other words, everything would have been perfect if some [expletive] program note author hadn’t started off thus: “K 415 is something of an odd bird, and has suffered abuse from various musicologists [unnamed]” then proceeded to list these anonymous complaints, and then—naturally—compared the work to the more sublime late Mozart. Sometimes that word sublime really bugs me. I swear, if we knew more about Mozart’s complexion, we would compare the sublimity of his zits.

Poor me! From the moment I walk on stage, I have to defend the work from the abuse of the program annotator. The listeners feel from the get-go they are getting a lesser meal, and they have not come to The Symphony to eat McDonalds.

It’s ridiculous and sad and stupid to have to defend a piece of such freshness and beauty. If the PNW (program note writer) had only managed to mention the very first entrance of the piano, for God’s sake. (Excuse me while I go beat my head against the wall.) My theory is that the piano is an instigator. Look at various entrances in classical concertos: there is often something “wrong” about them, something afoot, they come in too soon or too late, they take an awfully long time about something or they rush into things, they’re too simple, too innocent … There’s almost always a wink, a trick, a leap in there somewhere, something teasing, as if the orchestra were a big brother to be slightly mocked.

Maybe you begin to feel the orchestra has been going on too long? The tutti finishes off often a bit pompously, with a fanfare or two. The piano punctures pomposity. The piano’s a thief come to steal boredom.

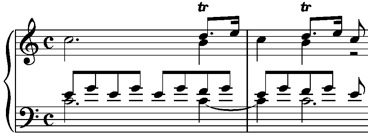

In 415 the piano-instigation begins right away: with two trills, syncopated, troublemaking against the beat …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Awfully close together, mildly complex to play, a bit hyperactive … twittering “D goes to C, D goes to C” … These compressed, quick trills with their kinetic energy generate a leap up to G:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Marvelous: but what to do with this G on the weak beat? The answer is fairly predictable, gravitational, we fall back down to the C we started with:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Fine. But heads up, here comes the fakeout:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Ha. Which of course is the reversal of the trills. You thought D went to C, well now C goes to D, with a naughty C# in the middle, boldfacing the joke: Mozart is laughing with you, at his silly game of do and re. At this exact moment, the left hand leaps into the situation, leaving its Alberti station … creating a sudden rush of events in the place where the phrase “should” be demurely resolving. Naughtiness filling what should be a polite piece of punctuation.

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Even if the PNW can’t bring himself to put into words the infectious mirth of the piano opening, this distilled essence of Mozart, the ONE thing you simply CANNOT neglect to mention about the first movement, the defining oddity, the magic-making curveball, is the SECOND THEME. (Beating my head against the wall again, sorry.) This theme doesn’t appear in the orchestral tutti, for the simple reason that it is not by nature “orchestral”: it belongs to a more intimate realm, it’s an idea for one person, not a mass. And unless you are a heartless person, PNW, you must take notice, somehow give homage to the way this theme gets slightly trapped in E minor, like a fly in the flypaper of melancholy:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… one of Mozart’s most beautifully artless themes. The structure is just 2 + 2 + 4, the simplest symmetrical thing in the world, but the first 2 bar bit drifts into E minor and gets marooned, leaving us to stare at E minor in bars 3 and 4. Then the second half of the theme … simply, beautifully, gradually, in the breadth of its four bars, with an arching melody, wakes us up and out…

Although this theme is in G major, it is “C major-ish” in its lack of concealment; it stares you right in the face; it subjects itself easily to dissection, but thereby loses none of its mystery or power. There’s no elision, there are no hidden joints, no inner voices concealing their subtle workings from us: just these phrases plain as day, doing what they do, the play of E minor against the “real key” … a cloud passing over G major and burning off again.

What’s more, this theme affects the “emotional structure” of the whole exposition …

1) charm of the opening, wit, laughter

2) passagework moving us to new key

3) sudden melancholy, lyricism, bittersweetness

4) passagework laughing the melancholy off.

Call me a hopeless Romantic, PNW, but I feel that the melancholy of the second theme infects or flavors the laughing surrounding material. I feel you can view the whole exposition at once, in a flash, seeing all the disparate emotions—and from this vantage point it hits you … that the comic material revolves around the seriousness of the second theme, as a center from which it takes profundity and pleasure.

One last thing that the PNW should definitely have mentioned, the single most important thing. As I arrived at the bar with the not so healthy potato chips, a very nice person I know ambushed me: “that last movement, it’s not really Mozart, right?” she said, with savage emphasis on really, as if, come on. I couldn’t help feeling she was emboldened by the PNW to talk this way, to presume to know what’s “really” Mozart. Grr. There I was in my world, where this movement was the most Mozartean thing imaginable, and there was her world across the beer-laden table: where transgression makes it “not Mozart.” The word really kept echoing in my head, unhappily.

She was upset by the Adagios in the last movement, which is the most marvelous weird thing that the PNW didn’t even find time to talk about. The rondo is just bouncing along, rollicking even, when Mozart interrupts these messages (his own messages!) to bring you an emergency announcement. Fermata, sudden slam on of the brakes, silence of suspense. Out of the blue: a lament in C minor, the piano in full diva over a lost love or something or other. Now, it’s patently ridiculous to have a depressive attack in the middle of a frolic; what Mozart is writing, therefore, is a joke tragedy. A giggling lament. It’s just beautiful enough that you might for a moment be seduced by it, drawn into its spell, briefly forget that we are in the rondo.

To write sadness satirically, with a twinkle in your eye, is truly wicked. Naughty Mozart!

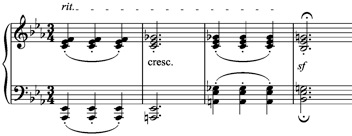

This Adagio rings twice, like the postman. Once near the beginning, and again near the end. After this second minor episode Mozart pulls out a double whammy of genius, piling weirdness upon weirdness. Let’s just point out that each and every phrase of the rondo theme ends with a little blip, tag, suffix:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… which of course is quite charming and silly. Out of this silliness comes Mozart’s master stroke: the last time we hear the theme, after this second tragic Adagio, suddenly this suffix multiplies itself, takes over, becomes an obsession, distributes itself through the orchestra, aww hell, let’s let some Brit explain it:

this fragment, tossed between piano and orchestra and multiplied ad infinitum, sails though the whole coda like a flight of fairies in a darkening wood …

Well put, Cuthbert Morton Girdlestone! The blip goes bananas, becomes a murmuring, a continuous laughter, and fragments of the theme echo, ever quieter, ever quieter …

A more beautiful joke could hardly be imagined. After the ridiculous lament comes the most serious, meaningful laughter. So often in the classical composers, the profound thing comes through the deflation of a false profundity, a pomposity punctured …. no not this claptrap, Beethoven says, but if I change one thing about it, slightly alter the proportions, sabotage the usual harmony somehow … there it is. Here too, Mozart directs our attention away from all kinds of normal possible endings, away from the Adagio’s temptations, away from convention itself to the transcendent possibilities of an idiotic suffix. Allowing the laughter to vanish into nothing, Mozart gives the feeling/illusion that it continues forever, eternally. A mirth that overcomes everything—lament, melancholy, fanfare–with its more profound insight, its fleeting permanence. And that, my friends, is really Mozart. Now hand me another potato chip before someone gets hurt.

floating until it finds its home on a multiple choice exam, there to be guessed at. (To this day I am terrified of Mozart’s biography.) I felt insulted, infantilized even, by this lecture style, and refused to take notes. But my housemate Sasha sitting next to me was furiously scribbling and scribbling. Sometime in the second day, a bit flabbergasted by his diligence, I glanced over to see what the heck was going on. There I read: “Mozart’s goat Nannerl dies; replaced by new goat, also named Nannerl. New Nannerl subsequently writes minuet.” I laughed out loud, abruptly, caught by delicious Mozartean surprise. I destroyed the non-mood of the classroom, caught a withering glare from the professor, but my faith in life was restored. In these pages of falsified facts, in their gleeful irreverence, there was more of Mozart than you could find in the entire New Grove Biography.

floating until it finds its home on a multiple choice exam, there to be guessed at. (To this day I am terrified of Mozart’s biography.) I felt insulted, infantilized even, by this lecture style, and refused to take notes. But my housemate Sasha sitting next to me was furiously scribbling and scribbling. Sometime in the second day, a bit flabbergasted by his diligence, I glanced over to see what the heck was going on. There I read: “Mozart’s goat Nannerl dies; replaced by new goat, also named Nannerl. New Nannerl subsequently writes minuet.” I laughed out loud, abruptly, caught by delicious Mozartean surprise. I destroyed the non-mood of the classroom, caught a withering glare from the professor, but my faith in life was restored. In these pages of falsified facts, in their gleeful irreverence, there was more of Mozart than you could find in the entire New Grove Biography.  You keep trying to return to that state where you “see” …. You add on layers, layers, like a cocoon, but then suddenly one day you scratch at one spot (perhaps that piece of information no longer seems important, relevant) and that spot widens, because you see the work more clearly now that you have begun to clear away the cocoon… gradually you are naked again, vulnerable, alive. Your skin feels raw. The work feels new. The work means something to you again; at one level you have forgotten everything you learned.

You keep trying to return to that state where you “see” …. You add on layers, layers, like a cocoon, but then suddenly one day you scratch at one spot (perhaps that piece of information no longer seems important, relevant) and that spot widens, because you see the work more clearly now that you have begun to clear away the cocoon… gradually you are naked again, vulnerable, alive. Your skin feels raw. The work feels new. The work means something to you again; at one level you have forgotten everything you learned.  She does not need to ask me how I like my eggs. Burnt smell of toast. The recording finished, a great project off my mind. A plate arrived in front of me, munch munch. No, no hot sauce. Barefoot, gripping coffee, I padded out to the deck without saying anything and sat looking at the trees. I’d brought with me Nabokov’s short stories, without really thinking about it, for no reason, and read:

She does not need to ask me how I like my eggs. Burnt smell of toast. The recording finished, a great project off my mind. A plate arrived in front of me, munch munch. No, no hot sauce. Barefoot, gripping coffee, I padded out to the deck without saying anything and sat looking at the trees. I’d brought with me Nabokov’s short stories, without really thinking about it, for no reason, and read: It’s impossible to know from our brief meetings, it’s likely self-delusion, but I’d like to think for her it’s all about the music, her smile is fantastic through the wrinkles, rippling through the wrinkles in a way that seems to be very musical. My old teacher, who had the most incredible, marvelous, subtle wrinkly smiles at certain moments in Mozart, said you should think while performing as if you were playing for the composer. But the composer is dead, most of the time. Sometimes I think it would be best to think of playing for this woman, or another friend, who knows and forgives everything.

It’s impossible to know from our brief meetings, it’s likely self-delusion, but I’d like to think for her it’s all about the music, her smile is fantastic through the wrinkles, rippling through the wrinkles in a way that seems to be very musical. My old teacher, who had the most incredible, marvelous, subtle wrinkly smiles at certain moments in Mozart, said you should think while performing as if you were playing for the composer. But the composer is dead, most of the time. Sometimes I think it would be best to think of playing for this woman, or another friend, who knows and forgives everything.

It got me thinking. Rachmaninoff will not generally whip the rug out from under you, he’s not an unreliable narrator. An emotion for him is something to “groove on,” something to obsess over, to let flourish. When he has a contrasting emotion, it is usually safely confined to a contrasting section: the form, the structure insulates us against emotional disruption (please note: the absolute opposite of above Beethoven example). He is trying to hold you, womb-like, in the spell of an emotion, to keep you embalmed. From the beginning of each section you can feel the gravitational pull of the climax, the place where that emotion will peak. He will build you up bit by bit, then wind down post-coitally, gradually, scattering embers of afterglow.

It got me thinking. Rachmaninoff will not generally whip the rug out from under you, he’s not an unreliable narrator. An emotion for him is something to “groove on,” something to obsess over, to let flourish. When he has a contrasting emotion, it is usually safely confined to a contrasting section: the form, the structure insulates us against emotional disruption (please note: the absolute opposite of above Beethoven example). He is trying to hold you, womb-like, in the spell of an emotion, to keep you embalmed. From the beginning of each section you can feel the gravitational pull of the climax, the place where that emotion will peak. He will build you up bit by bit, then wind down post-coitally, gradually, scattering embers of afterglow. In place of the single grooved-on emotion heading for its peak, they subsist on play, a wavering of emotions, of tone, from serious to light: they cherish less the emotion sustained than emotion fleeting. It’s a very intense difference of paradigm. In a way, it is ridiculous to think of Rachmaninoff and Beethoven as being both Classical Composers: they’re embarked on completely different projects.

In place of the single grooved-on emotion heading for its peak, they subsist on play, a wavering of emotions, of tone, from serious to light: they cherish less the emotion sustained than emotion fleeting. It’s a very intense difference of paradigm. In a way, it is ridiculous to think of Rachmaninoff and Beethoven as being both Classical Composers: they’re embarked on completely different projects. You get Wagner’s love letter to continuity, his modest assertion that he has achieved the most perfect endless melody, mastered the art of the infinitely gradated transition (violently different from Beethoven transition, above). Don’t you feel a certain desperation in some Mahler, a need to spin out his emotions at extreme length, as if off to infinity (9th symphony)? To make those altered states last, abstract hedge against death? It is one good definition of music’s purpose: this idealized notion of emotion, music as preserver or sustainer of emotion, as timeless place where a feeling lasts seemingly forever. Music is so excellent at creating states and spells, places where things can sing themselves out to the last drop. The Romantic era is how we WISH emotions were: endlessly prolongable, leading to satisfying climaxes, etc. etc. But the Classical era is (perhaps) how emotions maybe actually are: subject to inconsistency, wavering, shifting, vanishing, elusive. There is a line between this desire for endlessness and this humorlessness.

You get Wagner’s love letter to continuity, his modest assertion that he has achieved the most perfect endless melody, mastered the art of the infinitely gradated transition (violently different from Beethoven transition, above). Don’t you feel a certain desperation in some Mahler, a need to spin out his emotions at extreme length, as if off to infinity (9th symphony)? To make those altered states last, abstract hedge against death? It is one good definition of music’s purpose: this idealized notion of emotion, music as preserver or sustainer of emotion, as timeless place where a feeling lasts seemingly forever. Music is so excellent at creating states and spells, places where things can sing themselves out to the last drop. The Romantic era is how we WISH emotions were: endlessly prolongable, leading to satisfying climaxes, etc. etc. But the Classical era is (perhaps) how emotions maybe actually are: subject to inconsistency, wavering, shifting, vanishing, elusive. There is a line between this desire for endlessness and this humorlessness.