Can you believe it, I was just innocently surfing the net when I came across this:

It’s not often that Ives and Rossini share a clause. Now, I could splooge a bunch of ironic verbiage at you to explain how I felt, but I think this artist’s conception will suffice:

The night before I stumbled on this post, weird coincidence! I’d been stumbling down 9th avenue with friend M, in the warm aftermath of a perfect Manhattan. I remember the moment, my brain must have flagged it for some reason, the setting was not ideal, busy sidewalk, a clump of fratboys in front of a dive bar, one of them belched hideously, a hoarse sorority girl cackle escaped from the bar’s french doors, sailed into traffic. I fought screech and belch to let free something hours of humorless practicing had cooped up in me: how incredibly central humor is to Beethoven …

Around 1802 or so (I’m no biographer, look it up) Beethoven said to Czerny: “I am now going to take a new path.” I think this is a relatively important moment in Western Classical Music History, to be filed along with Bach saying to his wife one day “I’m just going to keep writing the same ridiculously incredible music I’ve been writing my whole life” and Stravinsky’s “I am now going to begin composing Neoclassical Music, which very few people will prefer to my early Russian Music, damn it, where’s my vodka.”

Beethoven says “I’m taking a new path.” The very next group of Sonatas he writes is Op. 31. Mr. Tom Service, just take a good listen to the first page of Op. 31 #1:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… the work of a jokester, first and foremost. Also, Beethoven like a child just cannot get enough of his joke, he’s obsessed with it, in fact the gag utterly depends on its insistence, i.e. it’s not just that the right and left hands can’t quite play together, but that they keep not being able to play together until, at last, after perverse amounts of anticipation, they decide to rush up and down the keyboard in an addled, maniacal unison. (How’s that for together?!?) Left and right hands are cast as characters in a slapstick routine. By the second theme, Beethoven’s left funny in the dust, he’s speeding on past silly …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… obviously, you don’t need words or images to be funny. Case closed? My point is not that Mr. Service is wrong, but that he’s SO wonderfully irritatingly wrong that there’s a shiver of pleasure and recognition when you turn his whole proposition inside out. As my key witness (there are millions of others!) I’d like to interrogate the opening movement of Op. 31 #3.

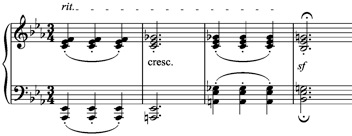

This sonata (the third “new way” sonata) begins with this unusual idea:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Much has been made of this beginning, for good reason. The harmony for instance! Beethoven starts off on a chord which would normally be considered too unsettled (strange to launch your vehicle from quicksand.) It is an audacious 7th-chord, but not an dramatic diminished-7th-chord, no, rather a lovely 7th-chord with a softer edge (“kinder, gentler”). The melody is lovely too: it begins with an impulse and releases to the weak beat (what we sexist-ly call a “feminine ending”), falling down a fifth in the process. These little attributes add up, they’ve been puzzled over pleasurably by generations of pianists, and without fail in masterclasses on this piece the teacher ends up begging the student to play more questioningly, more flirtatiously, more teasingly–it’s never enough, no matter how hard you try. By all accounts Beethoven was not a great real-life flirter but somehow such is life and art he wrote one of the great vexatious/flirtatious beginnings of all time.

What happens next?

Beethoven makes this chord denser, lower, deeper. He changes the soft-edged 7th into a menacing diminished-7th chord. Suddenly the music is transformed, nearly growling, we are in a radically different mood from the one the opening bars promised—ominous, dense, portentous. Beethoven instructs us to slow down, confirming that things are getting “more serious” (weightier) …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Maybe you also find it peculiar that Beethoven would start all flirty and then get immediately all ponderous and significant, before we even have a chance to settle in. [Possible theory for Beethoven’s lack of romantic success? ed.]

The delicious thing is it’s all a set-up. He’s promising, suggesting, preparing, and then finishes the phrase with …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… a throwaway cadence. Gravitas gone, like a popped balloon. Note that all the music up to this point has been unique, distinctive, stuff only Beethoven could write, but this cadence which wraps up the phrase is nothing, generic, anonymous, it’s stuff anybody could write. I get this image of someone crumpling up all the ideas of the phrase, throwing them over his shoulder with a smile, saying “that’s that.” The timing of musical events bears a suspicious resemblance to what we might call “comic timing,” the impulse of a great joke-teller to wind up expectation, to mislead, and then all at once, in a flash, release the punchline.

What you have is a phrase made of three different things

But it’s clear that C calls back to A, in that they both belong in the world of opera buffa—let’s say, the light and laughing. Whereas B’s clearly the stick in the mud. And so you see, structurally, the thing, the generative phrase of the work, depends upon and is built upon this wavering of serious and unserious, the heavy and the light: the serious encased, framed (mocked?) within the comic. This opposition is essential to its meaning, is actually its whole reason-for-being.

Enough of the first phrase, let’s move on. Beethoven repeats, reworks, adds cheeky grace notes etc. etc.

Presently it’s time for all this fun to end, to get down to business, to transition to the dominant key—that’s what all sonatas do don’t they? Beethoven seems to have this dutifulness in mind, a sense of the going-through-the-motions-always-modulating-to-the-dominant thing, because he rolls up his sleeves and commences his transition in a patently prosaic way:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

If you take just this passage out of context, it surely doesn’t scream Beethoven. It’s more the work of some boring 1760-something composer, the kind of composer whose symphony #938 you tend to hear in the morning on public radio: niche-filling tonal twaddle. I love it when Beethoven “pretends” to be mediocre. There is actually a lot of roleplaying in Beethoven, in his variations, especially: he pretends to be an oaf or a peasant or professorial Bach or bewigged Mozart, graceful or gruff, any number of adopted voices which wittily weave in and out.

This Boring Traditional Transition is going according to plan, it’s headed for the usual harmonic suspects (dominant of the dominant) and could easily be wrapped up … when we hit a wrong turn:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… haha, brilliant Beethoven stops mediocre Beethoven in his tracks. No time to laugh though, it’s too breathtakingly beautiful, this vision of the opening motive in the minor key, which we could never have suspected. The next measures (plaintive, melancholy, searching) in which Beethoven develops the B idea from the opening are crucial; the narrative which had been so jokey suddenly broadens, deepens. We’re astoundingly far from the dopey transition we began: Beethoven loves to juxtapose incompatibles, the prosaic and profound.

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The beauty of these bars functions: it creates a temporary spell, a bubble of seriousness. Now, for a joke to work, some part of it has to be “taken seriously.” That’s why many jokes are in 3s, with the premise set by two normal instances, which go as you expect (predictable, interchangeable, logical) and the third of course being the twist. Listening seriously and literally is an important phase in the process of being shocked, amused, disrupted. These bars, while seducing us, are manipulating us into being serious listeners. With this plaintive augmented 6th chord…

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… Beethoven clearly implies an upcoming “feminine” cadence, a gentle entry to the new key and theme very much in the melancholic preceding mood. However:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Notice Beethoven keeps up the dastardly disingenuous illusion till the last possible moment—even the downbeat of the offending bar is still piano—till wham! he thwacks out all those Fs, forte, hacking his way down to the guttural lowest register of the piano. The Beethovenian fox is in the Classical henhouse.

A transition is supposed to lead to, to smooth over changing harmonies, to prepare the way … But here all these notions–the normal definitions of transition–are mocked, trampled on. At the very moment I type this, sitting outside a cafe in Teton Village, looking up at the blissful morning mountains, a large dog has escaped from its owner (whose voice is heard tiredly scolding in the distance), and the dog has decided to squat poetically on top of the most innocent clump of daisies in the nearby perfectly manicured flowerbed. He is letting loose a wonderful dump on those daisies let me tell you, ignoring all the grass, the acres of other possibilities, the whole Grand Teton park for God’s sake, just to dump on those particular daisies. And I’m not saying that’s exactly what Beethoven is doing here, but it does seem a bit of a fateful coincidence.

The wry look of the elderly man at the next table is priceless, inscrutable.

Even if you heard every moment of this sonata more seriously than I have described up to this point, even if you’re perched in reverential bliss at the foot of Great Beethoven, at this moment you surely MUST realize that he’s playing you. He’s a trickster, an unreliable narrator, willing to whip out the rug out from under you, scheming behind your back how to mislead you next. This fascinating willingness even to disrespect his own beautiful inspirations, to destroy moods he has carefully created: a neglected ingredient of Beethoven’s Greatness.

After these loud F’s, we get barely a moment, a blip, a mere eighth note rest, and into the breach quietly sails the jovial second theme.

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Just to make sure we’re all on the same bewildered page, let’s have a quick recap of this “transition”:

quiet (sad) … thwack! thwack! thwack! … quiet (happy)

I’d propose, as analogy for this passage, another bit of slapstick: a man is walking along, he suddenly trips on a banana peel, falls, terrific crash as lamps and vases etc. are destroyed, there is a blip/moment of him behind the sofa or screen or whatever, but the next moment he is up again–pretending as if nothing has happened. The comedy is not so much the fall or the invisible clatter, but his rapid attempt at dignity immediately afterwards. Beethoven’s second theme appears instantly, with its Alberti bass, “as if” there had been a perfectly civilized transition, which there has not: this transition is comedy gold, pure irreverence. (Better than Tom Lehrer let me tell you.)

OK, one last thing I want to point out. This second theme is theming along, one phrase two phrase, in high spirits. It rounds off harmonically and then a bit of piano passagework begins:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Obviously, any piano sonata worth its salt must have some virtuoso passagework. Take a close look at that first bar … There are a delicious, irrational 17 notes in the second two beats of the bar … (“normally” there would be eight) … This often causes pianist mishaps, and provokes amusing student consternation. (How the hell do you fit them all in?) Theoretically, one job of the composer is to at least make sure the number of notes in the measure add up, particularly in passagework. Otherwise, anarchy: scales landing on the wrong harmony, flying every which way. But there is a sense here that Beethoven is making fun of this convention, flaunting it shamelessly … or could he be depicting the moment when the pianist “takes a wrong turn” in a passage and has to add an amazing number of notes to catch up? (Not that I’ve ever done that.)

This passage is the Energizer bunny, it goes on, and on, and on:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… it keeps curving up and down, swerving, naturally you begin to wonder: where could all this passage be leading, all this unprecedented scale-work be taking us? It must be something big. But when we get to the end of it, we have …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… the same old theme. The whole damned passage was unnecessary, a pointless curlicue, like an uneaten Cheez Puff. Don’t you feel Beethoven laughing at you, or laughing at his own joke, hoping you’ll laugh with him? (Visions of Joyce in his room alone, laughing hysterically while writing Finnegans Wake). Beethoven has visited upon us a pointless diversion, that is, pointless unless you find it amusing.

Have I made my point? Jokes are not accidental, occasional effects in this Sonata; this is not a serious piece with jokes in it, like those annoying “gag lines” that people scatter into their boring speeches. Humor is structural, form-defining, essential; the whole edifice is laughing, laughing at its core. The crucial junctures are often irreverent, the construction of the main idea is a masterpiece of comic timing, etc. etc. This is of course by no means to trivialize the piece, but to come to grips with it, with its gleeful transgressions, its badboy impulses, its joy set loose. And this is what I was trying to express after my Manhattan: the centrality of humor to this language of High Classical, to Mozart Haydn Beethoven, humor as an essential catalyst, a carrier of profundity.

—

The other day I was at a friend’s house recital and the first piece was the slow movement of the Rachmaninoff Cello Sonata. There was a guy sitting in the front row with a particular sort of rapturous look on his face. The rapture was deserved, the performance was beautiful, but his slightly glazed, cultish look … it made me a bit queasy.

It got me thinking. Rachmaninoff will not generally whip the rug out from under you, he’s not an unreliable narrator. An emotion for him is something to “groove on,” something to obsess over, to let flourish. When he has a contrasting emotion, it is usually safely confined to a contrasting section: the form, the structure insulates us against emotional disruption (please note: the absolute opposite of above Beethoven example). He is trying to hold you, womb-like, in the spell of an emotion, to keep you embalmed. From the beginning of each section you can feel the gravitational pull of the climax, the place where that emotion will peak. He will build you up bit by bit, then wind down post-coitally, gradually, scattering embers of afterglow.

It got me thinking. Rachmaninoff will not generally whip the rug out from under you, he’s not an unreliable narrator. An emotion for him is something to “groove on,” something to obsess over, to let flourish. When he has a contrasting emotion, it is usually safely confined to a contrasting section: the form, the structure insulates us against emotional disruption (please note: the absolute opposite of above Beethoven example). He is trying to hold you, womb-like, in the spell of an emotion, to keep you embalmed. From the beginning of each section you can feel the gravitational pull of the climax, the place where that emotion will peak. He will build you up bit by bit, then wind down post-coitally, gradually, scattering embers of afterglow.

The first movement of Beethoven Op. 31#3 has no climax, doesn’t want one or need one. Many (if not most) High Classical works don’t have climaxes in that sense.  In place of the single grooved-on emotion heading for its peak, they subsist on play, a wavering of emotions, of tone, from serious to light: they cherish less the emotion sustained than emotion fleeting. It’s a very intense difference of paradigm. In a way, it is ridiculous to think of Rachmaninoff and Beethoven as being both Classical Composers: they’re embarked on completely different projects.

In place of the single grooved-on emotion heading for its peak, they subsist on play, a wavering of emotions, of tone, from serious to light: they cherish less the emotion sustained than emotion fleeting. It’s a very intense difference of paradigm. In a way, it is ridiculous to think of Rachmaninoff and Beethoven as being both Classical Composers: they’re embarked on completely different projects.

Speaking generally—too generally—the Romantic Era gradually became more uncomfortable mixing the light and the heavy. Let’s take Liszt. He “laughs” through his Rhapsodies, Fantasies, etc. His serious works are serious! (“Faust” Symphony) But people deride the laughing works as fluff and the serious works as overdone—they feel too vapid or too earnest. By separating comedy from tragedy, the serious from the unserious, Liszt got two unsatisfying alternatives. Wagner purged laughter from his musical world (Ring, Tristan, Parsifal: pieces so laugh-free they are irresistible targets for satire). Chopin separated his lighter thoughts (waltzes, mazurkas) from the more serious (ballades, nocturnes, scherzos), except for a few special cases. Schumann … well he hits the light/serious sweet spot a few times (piano concerto slow movement!).

I would connect this light/heavy separation to something else: as the Romantic era wears on, you get a sense of this urge to prolong, to squeeze, to squeeze out emotion like toothpaste.  You get Wagner’s love letter to continuity, his modest assertion that he has achieved the most perfect endless melody, mastered the art of the infinitely gradated transition (violently different from Beethoven transition, above). Don’t you feel a certain desperation in some Mahler, a need to spin out his emotions at extreme length, as if off to infinity (9th symphony)? To make those altered states last, abstract hedge against death? It is one good definition of music’s purpose: this idealized notion of emotion, music as preserver or sustainer of emotion, as timeless place where a feeling lasts seemingly forever. Music is so excellent at creating states and spells, places where things can sing themselves out to the last drop. The Romantic era is how we WISH emotions were: endlessly prolongable, leading to satisfying climaxes, etc. etc. But the Classical era is (perhaps) how emotions maybe actually are: subject to inconsistency, wavering, shifting, vanishing, elusive. There is a line between this desire for endlessness and this humorlessness.

You get Wagner’s love letter to continuity, his modest assertion that he has achieved the most perfect endless melody, mastered the art of the infinitely gradated transition (violently different from Beethoven transition, above). Don’t you feel a certain desperation in some Mahler, a need to spin out his emotions at extreme length, as if off to infinity (9th symphony)? To make those altered states last, abstract hedge against death? It is one good definition of music’s purpose: this idealized notion of emotion, music as preserver or sustainer of emotion, as timeless place where a feeling lasts seemingly forever. Music is so excellent at creating states and spells, places where things can sing themselves out to the last drop. The Romantic era is how we WISH emotions were: endlessly prolongable, leading to satisfying climaxes, etc. etc. But the Classical era is (perhaps) how emotions maybe actually are: subject to inconsistency, wavering, shifting, vanishing, elusive. There is a line between this desire for endlessness and this humorlessness.

In the Romantic Era you feel that gradual erection of a wall between the light and the serious. It is important to reflect (did they?): this wall would destroy The Marriage of Figaro, or Don Giovanni. These two great operatic masterpieces are both symbiotic hybrids, comedy-dramas, in which humor is the indispensable meaningful foil. And don’t give me this ridiculous notion, Mr. Service, that it’s because of the words. Jesus! It’s not that Figaro is the most brilliantly funny script of all time, certainly! It’s the way the music manages to capture, bring alive, make suddenly ring true for us, its comic clichés: the way it captures emotion’s simultaneous truth and folly. It’s that the music laughs, more wisely and profoundly than any verbal gag could. Humor is a jolt, a trick of timing, a flash of the unexpected, but it’s also a fluid that carries forgiveness, empathy, generosity …

It’s sad to contemplate Tom Service’s image: Wigmore audiences tittering at Haydn, to congratulate themselves at “getting the joke.” Humor in classical music should not be nerdy, uptight, insidery, or smug. And sometimes it feels confined to those preordained moments, perhaps because of tradition or fear or etiquette or some other crap we can’t go into. Just to depress myself further, I looked on a classical music forum, with the topic: what’s funny in classical music? And you get a ream of special examples (Haydn this, Malcolm Arnold that, moments here and there) and then eventually hilariously it gets lost in a very unfunny discussion of Nazism in Wagner. Sigh. No no NO, I want to say, stop it, humor is no special example, it’s not a side stream, it’s not vacuum cleaners and celebrity guests and props, it’s the beating heart, it’s one of the main currents, one of the most wonderful. These composers, through flashes of genius, tremendous insight in timing, nuance, all the tricks of comedians, acrobats, thinkers, clowns, poets … they taught us how to laugh in tones: the only challenge is not to forget their living lesson.

25 Comments

Beethoven’s second theme appears instantly, with its Alberti bass, “as if” there had been a perfectly civilized transition, which there has not: this transition is comedy gold, pure irreverence. (Better than Tom Lehrer let me tell you.)

——————————————————————————

But not better than Peter Sellers’s Inspector Clouseau (the original). One can almost (NB, almost) imagine Sellers knowing and reading this sonata much as you have and transmuting it into the character of Clouseau.

Nice (and spot-on) piece (yours, that is), and with a perfect use of audio examples.

ACD

“Now, I could splooge a bunch of ironic verbiage at you…”

Well, it’s about time. Glad your back.

Oops! My,

One can almost (NB, almost) imagine Sellers knowing and reading this sonata much as you have….

should have read,

One can almost (NB, almost) imagine Sellers knowing and reading the above measures of this sonata much as you have….

ACD

More please, Meister, though obviously not at the expense of your Mighty Work (I thought you’d given up here, hurrah that you haven’t). You totally stole the show in that Schubert trio at the Wigmore, in a good way (because of the nature of that god’s piano writing). Wonder what you thought about the Elgar?

Fantastic post! Made me get out my piano score and recording to have a fresh listen. Ever consider writing program notes? The field is dying for someone who writes erudite but captivating stuff like this!

I feel it impossible to take the writer seriously. His reference to the “Energizer Bunny” suggests that he has at some point watched advertiser-driven television.

Great post. Looking forward to hearing you soon.

Reading that first question from Tom Service, “can you think of any funny classical music?” I immediately thought of a dozen Beethoven works. A few seconds more consideration brought to mind more examples than I could count. Even my four year old son laughs out loud listening to Beethoven–he particularly finds it funny when Beethoven lets his OCD with trills get out of hand. The other day it was his string quartet #14, which frequently abuses trills to the point of absurdity. Or the way Beethoven takes up a nice little theme then proceeds to blow it up like a balloon until it’s a grotesque caricature of a “nice little theme”, and then, to continue the metaphor, lets go of the overblown balloon, which then goes chaotically rocketing around, bouncing off heads, making children squeal, and scaring the cat. Really, what Beethoven *isn’t* like that? Yesterday we listened to the Great Fugue. Sometimes that piece seems like one huge joke, made up of recursively smaller jokes. Of course it is also stunningly amazing, leaving me unsure whether to laugh out loud or stand in quiet awe.

AMEN — thank you for this insightful commentary. As a composer of “humorous” music myself, it is difficult for me to understand how people think of Beethoven as a “serious” composer. So much of his music is incredibly strange, and absolutely dependent upon the sudden shifts and contrasts upon which humor relies. I think, for example, of the crazy exposed bassoon line in the last movement of the 4th Symphony, or the cartoonish interruptions in the last movement of the 8th Symphony. The critic Wolfgang Robert Griepenkerl had some fascinating things to say in the 1800s about this aspect of Beethoven’s music, which he called quintessentially German and compared to the writing of Jean Paul. Interestingly, classical music lovers have become conditioned to the idea that the weirdness of the music of Beethoven is actually normative — we “expect the unexpected.” In fact it IS now the norm, in the sense that it is the foundation of much of the standard Romantic Era repertoire. So ironically, it is difficult for 21st century listeners to hear the humor in classical music because it is so central to the style.

Agreeing with Carl Schimmel, I also thought of Beethoven’s 8th, especially the opening of the first movement, with those explosions of energy and abrupt stops. It’s almost like a comic break when you consider it falling between the Seventh and the Ninth. It’s like a zippy Mini convertible parked between a pair of turbocharged Porsches!

Brilliant, brilliant, brilliant, brilliant, thank you, brilliant, brilliant, thank you, brilliant, thank you, thank you, thank you!

I still remember reading through Op. 31, No. 3 for the first time. Immediately after playing those opening measures, I started to giggle. -Had I misread the notes? -Was this some sort of misprint? -Did this chord even exist during Beethoven’s lifetime? It was just too jazzy. I believe I even grabbed another edition of the sonatas off the shelf of my teacher’s studio to see if it was indeed a misprint. Of course, it wasn’t. Happily, it wasn’t. And the remaining movements are filled with many LOL moments: that great scherzo in 2/4(!), the leaping theme of the Trio, and the “chase” of the finale.

It seems to me that humor, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder – which also means that humor often depends on the ability of the listener/receiver to get the jokes, in all their different varieties. (I also happen to find quite a bit of Romantic music quite hilarious, except I’m often laughing at it, not with it.)

Thankyou so much. Absolutey Brilliant writing. I laugh my way through late Beethoven quite regularly, especially the opus 135 Quartet.Now I at least know I am allowed!

The thing is though, the best jokes don’t need to be explained…

Excellent post. The first time I really got this about Beethoven I was in college and listening to the Moonlight Sonata all the way through for one of the first times, and it dawned on me that the familiar pretty beginning was just a setup for the big middle-finger-in-your-face of the rest of it. I felt that he was cursing the audience and laughing at them at the same time, going “oh, you wanted something pretty? Well F you!” over and over. Didn’t think he wanted us to laugh back, though.

Thank you for the wonderful blog. Isn’t Peter Schikele (PDQ Bach) also worthy of inclusion among “funny” composers? (Any piece for “viola four hands” has got to be funny.) On the classical music forum, several people mentioned Debussy’s satirical take on others’ music. So we could include Saint-Saens’ Carnival of Animals, and Ravel’s La Valse with its citation of J. Strauss.

It really is odd that people seem not to get the humor in music. Many Beethoven pieces seem funnier to me with each passing year, especially a lot of the earlier stuff. I was fortunate to have a piano teacher many decades ago who was able to make audiences inadvertently laugh out loud during his performances op. 31, no. 3. Ever since, I’ve felt that the majority of performers just don’t get it. Or else are afraid to share with audiences what they really think is going on, for fear of something, but what?

By the way, a temporally Romantic composer who wrote a great deal of brilliantly funny and witty stuff is Alkan. But he was at heart either more Classical (or presciently Modern) than Romantic, I think. Sometimes it seems as if his tongue was congenitally shaped to be inside his cheek, and it is often hard to know when he is really being “serious”. Even when his music isn’t overtly funny, it frequently has very strong undercurrents of irony. Unfortunately, most of the pianists who have recorded his music tend to get wrapped up in other elements of his art (typically, the fantastic virtuosity some of it requires), and neglect his humor (or they may not even realize it is there).

This is fantastic. Thanks! Makes me think of humor in Satie — not in the titles and dadaism, where the typical Satie listener/scholar finds the humor– but in pieces like “Je Te Veux,” which is just burning with a half-sarcastic, half-sincere burning desire for the unattainable romance. In Je Te Veux especially, one can hear Satie stumbling drunkly home in Arcueil, singing to himself about the object of his desire. Very beautiful, very funny.

Far be it from me with a mere 3.67 to point out to a 4.25+, but it’s a AbM6.

Congrats on Carnegie, looking forward to hearing the Ives. And what about 4”33″. I do remember not a little laughter from the performance.

For the last 15 years or so, Beethoven has seemed to me a lonely uncle who comes over occasionally to do magic tricks for us kids.

Welcome back, Mr Denk! Have been looking forward to another wonderful bit of writing. I think you’ve hit the nail on the head with this one… humor is so integral to so much classical music that to miss this fact is tantamount to missing the point altogether of a lot of pieces. As you say, humor is just another way of communication, and when married to all the other facets of the human condition through music, it can be as profound as the most eloquent attempts to “say” or “mean” something in an overtly brooding or melancholy way. Please keep up the blog when you can, there are a great many out here who appreciate your insights!

By the way, I saw you perform in Denver back on December 1st of last year, and wanted to let you know that I truly enjoyed your performance that night, especially the Beethoven and Ligeti. Now THERE are two fantastic partners in crime, with marvelous profundity and joyous perversity in equal measure!

Rage over a lost penny!!!!

I’ve compared Beethoven’s stuff to the “Sixth Sense.” You think there’s a twist — and he knows you think there’s going to be one — so he uses his foreknowledge of your anticipation to totally punk your ass time and again. And because he’s just so good, you let him get away with it. Time and again. I don’t know if I’d call it humor, but damn it’s fun.

As for humor in other pieces, the Haydn stuff for example, I think that humor depends on the fact that the music was often apprehended by people who were playing it at the time. More people were hobby musicians back in the day, as opposed to nowdays when most people will grin stupidly and tell you, “I can play the ipod!” when you ask them if they play anything. I think the humor in a lot of the older music depends on it being apprehended by people for the first time as they played it, and not as they sat there and stared at a speaker. They were more practical jokes played on amateur musicians than intellectual jokes played on an audience.

I also think (translation: it’s just occurred to me now as I’m babbling) that maybe when the improv aesthetic left classical music, it took a lot of humor with it, too. There is a feeling in an audience when you see someone improvving really well that will make someone want to laugh, just from delight. Montero gets this reaction a lot. And once you’ve loosened up the audience by getting them to giggle a bit and grin from sheer joy, you can get them to laugh at little bits of humor, too — like when you’re listening to Time for Three and suddenly the theme from the Simpsons floats out at you, or there’s an upwelling of Foggy Mountain Breakdown in the middle of the Bach Double. That sort of “off the cuff” music-as-its-created lends itself a bit more to humor. It may be that the relative absence of humor from the Serious World of Classical Music came into existence about the time that improv got more or less banished.

In both cases, the “jokes” are apprehended the way jokes are supposed to be — in real time, as they are happening, and they’ve never been heard before. Either Montero makes you laugh your ass off when she turns the Hallelujah chorus into a tango right there in front of you, or Haydn made you trap your finger under a string in a scherzo while you and your 18th century musician buddies were sharing some ale and playing cards and trying out the latest new piece. Jokes don’t do well at all when they are canned, scripted, and have been told a thousand times — it starts to be like Henny Youngman telling that damn joke about airline food is fit for a king for the gajillionth time. Jesus Henny, TELL A NEW ONE! (es, I know he’s dead. 🙂

So while I do have to admit that humor in classical music shouldn’t be a collection of insidery in-jokes … it is, all too often Henny Youngman telling the same damn joke for the gajillionth time. I think Tom Service has an unfortunate point, to be honest, even if we don’t want to admit it. Jokes require real-time spontaneity, and classical music has lost some of that since improv was excised from that world, and since people stopped playing instruments themselves as a hobby.

A hugely masterful post – thanks.

2 Trackbacks

[…] Jeremy Denk says classical music can be funny. […]

[…] Denk, pianist. Congratulate Yourself, Beethoven Reply With Quote + Reply to […]