[Posted on Craigslist]

Bemused but occasionally cranky pianist, 36, seeks similarly-minded other for longterm relationship “with benefits.” Does not enjoy discussing real estate or humidity. Allergic to nuts, the Tchaikovsky Trio, and unmarked retransition ritards. Serious candidates must be able to sit through the occasional slasher flick, mindless Hollywood thriller, or other piece of mass-produced drivel; must be subsequently able to endure endless pseudo-intellectual analysis of same. Gin drinkers preferred.

***

Hey, read your ad and was quite intrigued. Me: 5’7 and a half, sturdy, well-versed in music and related arts, something of a workaholic, but up for fun now and again, great lover of coffee, food, drink, and the pleasures of life… interested?

***

Well, you do sound interesting. But I’m finicky. What’s the catch?

***

Hmm, the catch: I suppose I should tell I have kids. And here’s something weird: I wear a wig.

***

Wow, a double whammy. Kids … are those the little noisy creatures one sees perched in the small vehicles that often block access to my beverages in Starbucks? [snark] I’m looking for someone of substance, for sure, and I’m really trying not to be superficial about appearances … but I have to confess the wig thing has me a bit “wigged” out. Can you send me a pic? Also, you never mentioned your age…

***

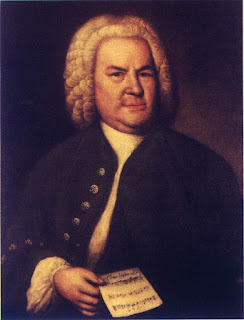

Sigh, I guess it’s time to come clean. Here’s my pic:

People say I’m “timeless” which I guess means they can’t really tell how old I am? … whatever. One good thing about being dead, the whole age thing kinda gets less pressing …

I realize this is a lot to take in; hope it doesn’t freak you out. I think I’m worth it, though. Am enclosing my d minor English Suite so you can get to know me a bit better.

***

Well, this is … interesting.

As a dead European composer, you understand you’re sort of an unusual relationship choice. I was really hoping to date someone more or less alive. Of course, I’ve *always* dated living people so this might just be the fresh start I need.

***

I’m so glad you decided to give it a shot. Why don’t I come by your place sometime in the afternoon tomorrow?

***

OMG that was some date. Did anyone ever tell you you give amazing retrograde inversion? And I’m still dreaming about your descending chromatic bassline.

***

Glad you had a good time. IMHO chromatic and diatonic are really the two great linear forces at work in music and I love to watch them bump and grind against each other. Anna Magdalena used to help me with that in between minuets, if you know what I mean.

***

[3 months later]

… my friends will tell you I’m something of a committmentphobe, but I think you’re someone really special, a “keeper.” There’s just more and more to you, the more I look, and I never get tired of thinking about you …

I have to tell you, though, I really think it’s time to LET GO of the whole Telemann thing. I mean, so he got the job you wanted, and you had to keep teaching Latin to those “little brats,” big deal! I mean I think it all really worked out for the best … think of all the joy you’ve brought so many people.

***

You know, thanks for listening … sometimes I feel like I can go to peaceful places in my music that are hard to attain in reality.

By the way I noticed you had some unusual looking scores on your piano. Not anything I would write for sure! What gives?

***

JS, I’ve been meaning to talk to you about the possibility of an open relationship. I mean, the time I spend with you is SO AMAZING, but I sort of want a little space, I want to be free to see other composers …

***

Honestly I don’t know what to say …

… the other night, after the 5th Partita, you just had a beer and went straight to sleep! … after I slaved for weeks over a hot harpsichord writing it! Sometimes I can’t help thinking you just love me for my music. And how can you love that other stuff too?

… as they say in my native tongue, ich habe genug. Don’t be sad; we’ll always have the Allemande of the Fourth Partita.

***

[chat with anonymous third party]

J: Well I guess that didn’t work out ?.

X: Live and learn

J: I’m seeing this other composer now, Charles. I think he has some gender issues, though, kind of obsessed with masculinity, etc. etc.

X: Oh, you know what that means [wink]

J: Yah. Ok, gotta practice

X: ttyl