In many Romantic lieder, the pianist is the river, while the singer is the melody above: the person addressing the river, throwing themselves in the river, or participating in other river-related mishaps. I’m down there burbling or babbling or sometimes even burping (if I’ve had enough to eat just before the concert), and the singer of course gets to be all emotional and crap like that.

The pattern works; it separates the texture (here’s the melody everybody! and here’s the accompaniment! follow the bouncing ball!); it makes for easy listening of a sort; and later Romantics can be forgiven (perhaps?) for simply having no imagination except to do the same, but more and more and more. By Rachmaninoff, for instance, it has to be torrents and torrents of river in the piano and the melodies generally need to be pretty intense too just to be heard over his gushing faucets. (At the beginning of the 2nd concerto, the pianist is the river, at the beginning of the third, briefly, the orchestra is the river, etc.) I like to think of these Romantic rivers always being situated in really dramatic but cheesy locales with savage drops and rocks and flowers and sea lions (?) and of course all these notes cost me countless hours of my life, putting in stupid fingerings so I won’t be splatting all over the place (but I’m not bitter at all about that). Audiences seem to get a big kick out of these vast numbers of notes, and sometimes I enjoy them too.

[If you’ll indulge me …]

The Allemande of the D major Partita is a river, too. I totally feel the line of the whole thing, like something I could never fit in my hand or in my mind, with a maddening lack of boundaries, but I know it’s a line, a stream, and it can be followed. In its sinuousness, it wants to be followed, navigated.

To be super factual and comparative! … the D major Allemande is unique among the Partita Allemandes (and perhaps Bach Allemandes in general) in its rhythmic treatment. The B-flat Allemande is a continuous stream of 16th notes … the C minor Allemande also … the A minor is more ornate but still duplish, with little dotted rhythms and flourishes of 32nd notes … I could bore you with more … but here in the D major, various “incompatible” rhythmic elements are coexisting, rubbing against each other. Even mid-phrase, the melody drifts from 2s into 3s, from one groove to another … it is one stoned tune! Sometimes I have the sense that, for Bach, something is going “too easily,” and then triplets have to intervene, creating drag, braking, and then too this drag must be released into florid 32nd notes: in other words, the melody is tractable, willing to shift its own flow, malleable, reasonable if not rational.

In the spirit of carpe diem, I’d like to take this juncture in the post to really get down and funky with one of the most boring terms in classical music: style brisé. What is it? There is no article in Wikipedia (leaving me helpless); the term comes back to me mainly, hauntingly, from music history class, and yet even in notes from my wonderful music history professor, there seems to be some sort of helpless flailing around meaning, a sort of you-know-it-when-you-see-it-ness.

It’s an arpeggiated style (whatever that means). It’s a French thing (ha). It means “broken style” and (here is the point?) it’s this sort of constant interlacing, crossing of the voices. Clarity and simultaneity are not its virtues or desires. Broken style is broken up like ground beef in a pasta sauce. It does not like to settle down a chord, chunk! It likes to let chords unfold in time, in facets, details … but you see, it’s not at all like Rachmaninoff in that way (those arpeggiated passages are mainly written out simultaneities, sort of time-fillers, ways to make the chord “last longer”) … here the arpeggiations are all melodic, or close enough … and somehow Bach is “all up in” the idea of the Allemande, its kind of raison d’etre which is: through constant interweaving of different ideas and textures, to create a kind of evasive, sinuous, non-repetitive flow.

As a corollary, Bach is not too stern with his voices. There’s kind of a live-let-live vibe going on. if they feel like hanging around for a while on one note, they do; and if they feel like they have something to say, they do, or if they have to move, etc. etc., and there seems to be little hierarchical angst or attitude. Unlike in fugues or fugatos, there is no sense of “order” of entrance, of strictly staggered schemes; stuff happens. Yes, in the D major Allemande the top voice is a diva, but one unusually receptive to all sorts of suggestions from below, which is good, because those other voices have such spectacularly beautiful things to say; they relate to the top voice subtly, not overtly, like friends who know exactly what to say in a heart-to-heart. This all goes with my contention that this Allemande is somehow not something that happens, but an enchaining of happenings, or the way something happens (to quote Charles Ives): a sequence of things that cannot be untangled from the other; the voices are not separable, the rhythms are not separable, all is subject to drift and fusion.

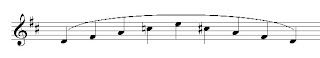

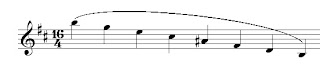

Along these lines, I have a favorite spot in the piece:

There is a lot of “crossfire” in these two measures, many interactions, twists and turns; it is a kind of strange juncture, almost a “breakage,” but particularly in the second measure, I feel such a sweet amity between the voices, I really really do. The concords they reach are so touching. The (3 or maybe 4) voices seem at this and similar moments—if this does not strike you readers of Think Denk as ridiculous—to love each other. (Or to show us humans what love might be.) Though, it is true, the bassline “does a naughty” by cadencing deceptively on the downbeat of measure 18 (E should go to A, not F#, right???) the naughtiness is quite felicitous (aka awesome) and the rest of the voices don’t seem to mind; they even celebrate their deep sibling’s flight of fancy, each contributing in the course of the measure, helping, agreeing, moving things along, passing the current through, up, around whatever obstacles any of them might have thrown in the way.

This river’s not going express; nor does it feel like a local. It’s able to smell the roses but it does not let stoppages become static. And therefore it can break itself constantly into fragments, disperse, and then again, again, it seems to refashion itself on the rebound into a radiant whole.