When I mention to people I’ve played Chopin on my recitals lately, I tend to get a curious reaction–a slightly sour look with a parental, passive-aggressive question mark swirling around in it. Oh, dear, really? From their oblique remarks I glean an implication: why would you play Chopin, since you are a supposedly thinking person (i.e. “Think Denk”) and Chopin, well, dot dot dot. I’ll admit it, I often feel vaguely insulted by these reactions, both for my sake and for Chopin’s. It’s a duet of outrage. One part of me thinks I’m certainly dumb enough to play Chopin!, while another impotently huffs, Chopin is not dumb, and you’re a boorish nincompoop. Over martinis, I consider what level of drooling lobotomy I would have to have for people to think it OK for me to play Chopin.

A person quite close to me feels Chopin is pure boredom in a jar. I told Mitsuko Uchida once that I might have trouble choosing between Chopin and Schubert, and the storm that crossed her brow would have shut down the airports for days. I’ve had my moments of doubt too: occasions when I sat through the E minor Piano Concerto (a wonderful piece, IMHO) as performed by such-and-such marvelously talented young pianist and I couldn’t reconcile this superficial finger-doodling and quasi-emoting with the shiver I know, the deeply delicious savoring of passing notes, the web-like harmonic world that Chopin holds me in … hours spent at home, passing your fingers over the piano, you’re playing and you’re shivering at the same time, trapped happy fly eaten by genius spider.

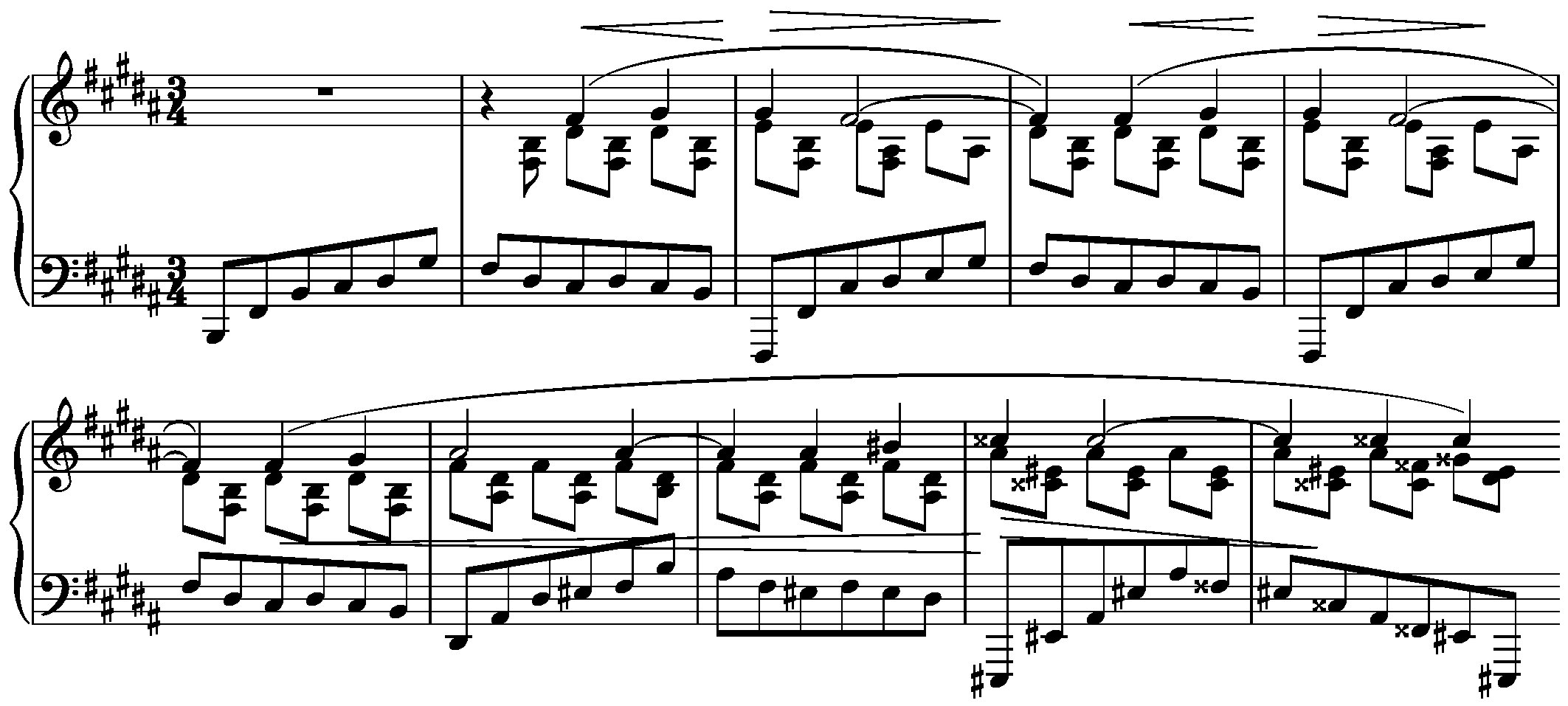

Just take the slow section of the Polonaise-Fantasie:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… And you thought nothing more could be wrung out of that old whore, dominant-and-tonic! Hard to know why this is so astoundingly beautiful. In the left hand a wave, rising-falling, and in the right hand the intersecting wave, more muted, as if a mere reflection of (or commentary on) the larger wave. Compare this to the climax of Tristan und Isolde:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Which is almost the same–the same gist, with a reversed harmonic polarity–but Chopin has drained it of Wagnerian emotional hyperinflation, burst the bubble of the grand demonstrative stage, distilled from I and V a purer love: perhaps just the intimate (but often seemingly almost erotic) love of Chopin for the piano itself.

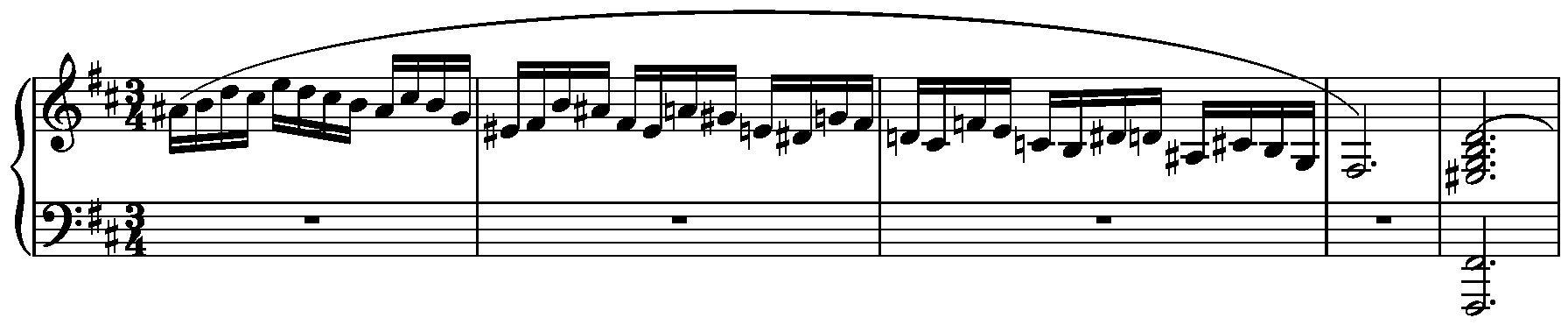

This pure moment would be so much less, however, without its bizarre and brilliant lead-in. We start with the bluster of a diminished seventh chord, here:

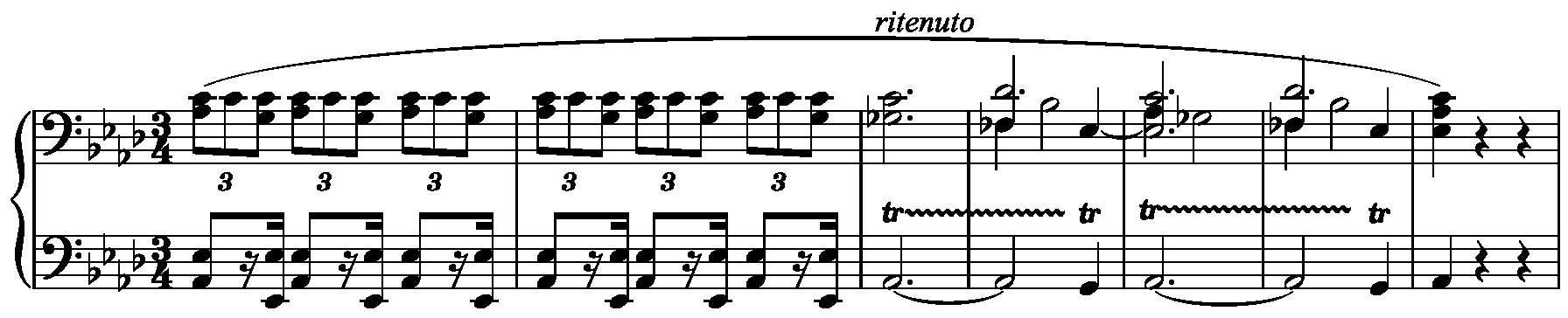

and that explodes into a massive chromatic whorl:

Standard Romantic expostulation? Maybe you have the feeling that this is a bridge too far, the chromatic’s too oozy, the drama’s outsized: you’re right about that. For the bluster somewhat obviously, tiredly wears itself out, the curlicue oozes downwards, loses steam, loses faith in itself–and we finally settle on a lone F#. What was the point? If you feel also that the new key has not quite been prepared by all this flailing about, that the transition has been ineffective, you’re right about that too: for, now, a “true preparation” comes as a rebuke to the “false preparation.” Look, see, the F# is looking for a context; Chopin makes us listen to it for a moment, alone, then with a strangely sour chord,

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

then alone again, then with the “right” chord, waiting waiting waiting,

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

and then the epiphany comes, utterly different from any previous moment in the piece, or any moment to come:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… magic doorway of the other. Chopin’s simplicity rebukes Chopin’s complexity. The Genius of Chopin is sitting there, in his self-rebuke, sandwiched between an almost-clichéd chromatic transition, a pedal point, and a lyrical slow section rocking between the two most common chords there are: this glimpse of screw-you-I-can-write-something-so-beautiful-that’s-made-of-almost-nothing, as an unearthly transition between things that are also almost nothing. The four mysterious bars are a messenger, unveiling a new chapter before vanishing, a chapter which turns out to be the quietly beating heart of the piece.

I want to go back to that long pause on the F#.

One of the great and strange elements of the Polonaise-Fantasie, one of its “themes,” is that the act of listening is woven into its fabric. Chopin wants you to listen–carefully! thoughtfully!–to certain sounds, certain pitches, certain moments; the structure of the story he is telling is utterly dependent upon this listening. But he knows that listening is an inherently lazy activity, often thoughtless, often lulling itself into complacency. Just look around the boxes of Carnegie some night if you don’t believe me on this. [Sometimes I look out into the crowd while I’m playing and I will see some rapt individual beaming ecstasy, and I will tell myself not to look any more, but then I can’t help it, I look around later and there is some guy searching the back of the program for classified ads and clearly desperate to get out of my concert and straight to the liquor store and then home to ESPN.]

Anyway. So Chopin writes “enforced” listening moments into the piece–strangely arresting moments, like that F# held, alone, then heard against an astringent dissonance, then heard alone again, then heard against the “correct” dissonance, the dominant seventh–moments that enact, in a kind of slo-mo, the very process of hearing dissonances resolve against a pedal …

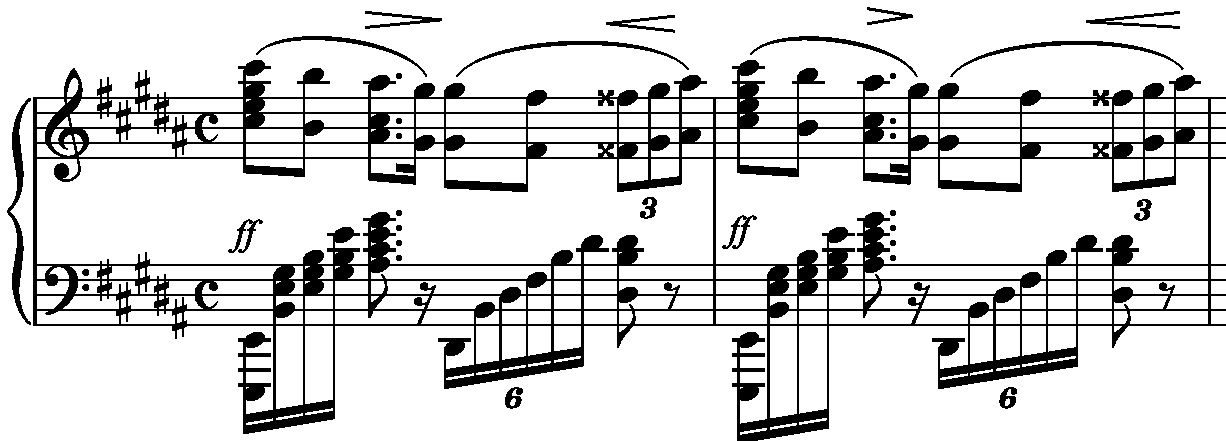

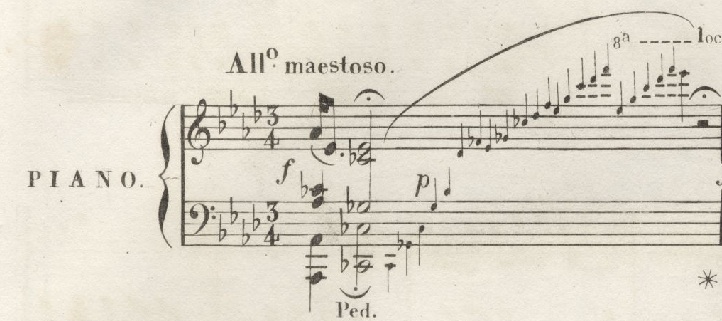

The beginning of the Polonaise-Fantasy is an extraordinary example of this. Chopin begins with two announcing chords … and then follows them with a long unmeasured arpeggio (prolonging the harmony of the second chord) …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The same gesture of chord arpeggio is then repeated:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

These arpeggios have, in a way, a mundane purpose. They fill up the thwunk and the attack of the piano with beauty: the arpeggio sails languidly into the dead space, the still lagoon of the note’s decay. But this is not all. A kind of rhythm is established, in this very unrhythmic beginning, a rhythm of events: chords, fermata, arpeggio … act, stop, listen. The pauses are quite long–deliberately almost too long–and so the action is weighted towards listening (thought) and against action. The pianist “does something,” plays two significant or signifying chords, then is forced to meditate on what he or she has done: the arpeggios are parentheses seeming to be inaction, but perhaps are the truer action (meditation, understanding). In creating this pace of events, by “building in” reflection and observation, Chopin creates an unusual kind of beginning. This piece does not begin in order to begin, but rather in order to summon some spirit to allow us to begin: in other words, the introduction is an invocation. And of course the spirit Chopin is patiently invoking is sound, the resonance of the piano, the ringing of the wood, some appreciation of the beauty of the struck harmonies drifting through time.

This often odd “enforced” listening to retained, held notes persists. For instance:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

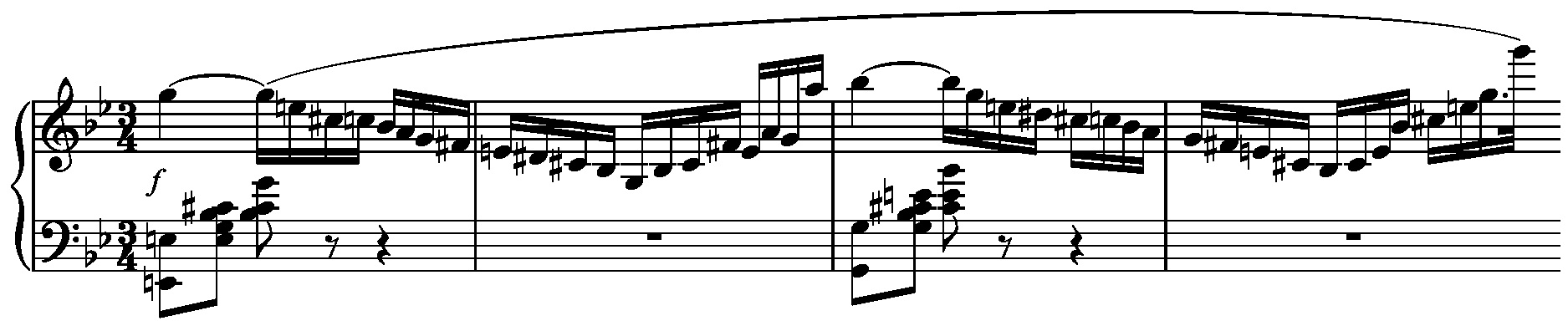

Chopin extracts, strangely, the middle voice from the chord, forces us to listen to it for a moment alone, then uses it as a pivot to the next event. He’s trying to encourage complex listening skills, by delving into the crusty middles of chords! Definitely not a superficial thrill, but a thrill for those “in the know.” Or perhaps this example, where we land on a B-flat:

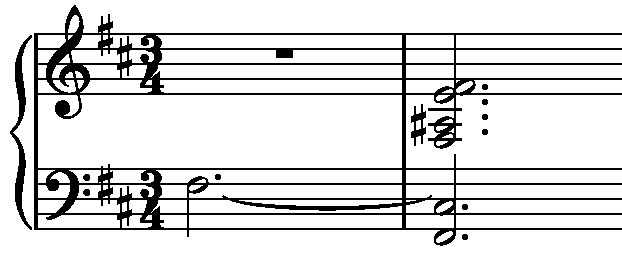

… and twice Chopin makes us listen to the B-flat alone, while the rest of the voices attempt to cadence around it, before ending simply, perfectly, profoundly:

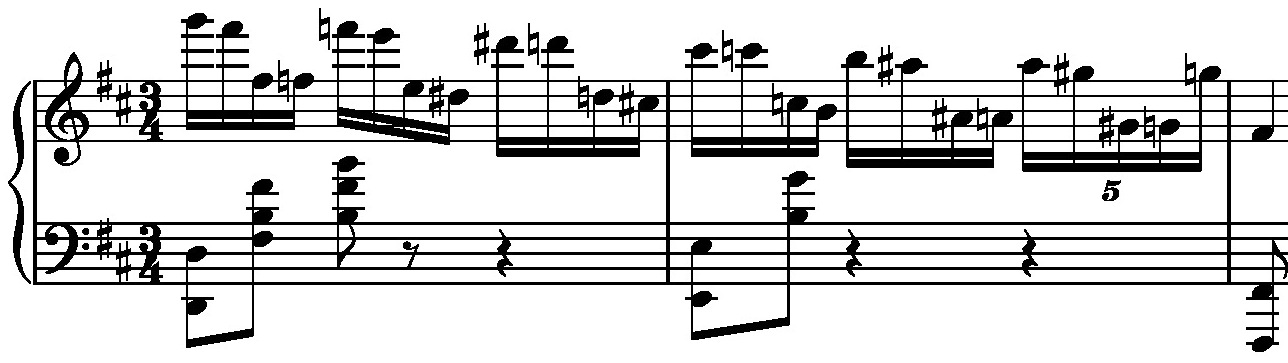

But the most wonderful, strange example of enforced listening is at the end of the piece. We are flush from the ecstasy of a climax, an A-flat major explosion of the slow section theme … this ecstasy is slowly winding down. Chopin gracefully abandons the energy of the climax, unravels it in circles, and in the echoing of this happiness he finds something unlooked-for, a kind of dark “second thought”:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

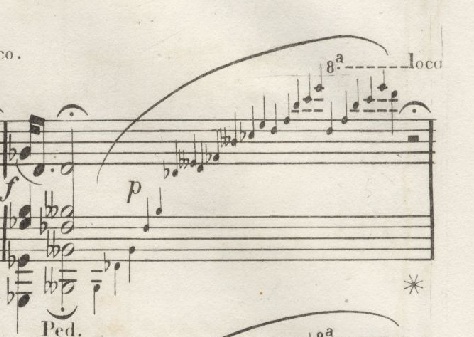

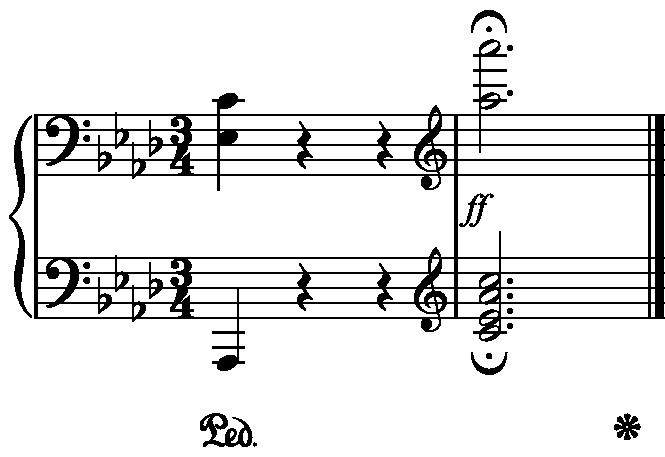

… This darkness (or sadness, if you like) complicates the emotional image of the end, disrupts the fading bliss. And then Chopin throws over the ending a magnificent anomaly. As you see above, the dark measures cadence, we have a quiet, low A-flat major chord … the piece might be over? … and then while the low chord still sounds in the pedal, Chopin instructs the pianist to play one loud A-flat major chord, in the high register.

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Yow. The luminous final chord then resounds against the dark overtones of the previous bars: a jarring double image, a bright light on a dark canvas. The effect is not either of those chords, but how you hear them decay together, their resonant death.

The pianist’s typical virtuosic, towering gesture is to try to “sum up” all the registers of the piano at once, to be everywhere at once, to be (sort of) an orchestra. This is the pianist equivalent of the phallic, midlife crisis truck purchase. Chopin is past such insecurities; here, things are definitely not all at once: the chord, the sensation, the understanding of the ending is assembled from disparate parts, foundation and overtone mismatched. It’s as though two endings are superimposed–the brilliant ending that could have been, the sad ending that could have been–and therefore the actual ending is a rare hybrid, with genes of two could-have-beens.

Chopin could have finished the piece with a surge, one last surge to victory (surges are so popular these days); but no, he is not finishing a piece, he is finishing a thought; this is a moment not for the pianist’s glory but for one last, complex listening. Listening “between” two layers of sound. My late great teacher used to talk about Chopin’s hypersensitivity, his mind “like the paws of a cat,” and then he would take his stocky Hungarian body, once employed as prisoner of war to break stones in the Carpathian mountains, and with a few gestures and a lifted eyebrow he’d make himself seem as light as a cat’s step, and with feathery gestures of his hand he’d come down on the piano, on some simple but illuminating pair of harmonies, and then his eye would meet my eye and I felt he was trying to communicate to overprivileged American me Chopin’s vast refinement of thought and elegance and culture, how he valiantly rescued the original from the salon’s tremendous pressure of cliché … elusive fragile epiphanies of sound, standing on the summit of the piano’s wood-and-wire construction … well, that’s the Chopin I love, and he’s no dummy.

21 Comments

Great post, thanks for that. May I: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Reb4yRWwwjg and http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M16axUCCXUw ? What a performance! Cheers.

the arpeggios are parentheses seeming to be inaction, but perhaps are the truer action (meditation, understanding)

so good to see you back jeremy, with chopin!

It’s as though two endings are superimposed–the brilliant ending that could have been, the sad ending that could have been–and therefore the actual ending is a rare hybrid, with genes of two could-have-beens.

and this could be said about much of walt whitman’s poetry, no?

It is more than OK for you to play Chopin. And especially to share such intricate details about your relationship to his music. This post is a little slice of heaven, in my opinion. Must add to my list: hear Denk play Chopin live. Some martinis added into the picture would be nice, too.

Jeremy:

I concur that the heart is big enough to love Chopin and Schubert, and on that subject, my wife and I loved your Chopin performance in (ugh) West Lafayette. Your Ives too. And your Mozart. Welcome back to BlogWorld. We’ve missed your missives.

Jeff

I hadn’t thought about this piece in over ten years. Thanks for reminding me how spectacular it is. A highlight of the soundtrack of an earlier part of my life. Chopin is no dummy and my 18 to 21 year old self was apparently no dummy being into him.

We are at a crossroad in time where the re-appreciation and re-introduction of Chopin and Bach (Goldberg Variations) are essential. Banality of professional musicians is seminality to the ears that sense classical music to be elitist and/or dead. I applaud your selection of pieces and hope you continue down the Walt Whitman path to music…you never know where it might take us all.

Welcome back. Your last two paragraphs here are sublime.

Wonderful post, thank you!

Yes, Chopin can be all these things, if the one playing him brings all these things to the music. It’s common to hear him as soppy romanticism; it is refreshing to hear him as “screw-you-I-can-write-something-so-beautiful-that’s-made-of-almost-nothing.”

I’ve posted a very interesting passage from Adorno where he discusses Chopin with considerable insight, making some passing references to Schubert.

http://martinfritter.blogspot.com/2009/12/chopin-for-dummies.html

Also some Michelangeli and Rosenthal.

Jeremy, you’re a smart guy and Chopin was a smart guy. His music is very sensual, and it’s possible that that sensuality represents quite an essential, paradoxically smart value on Chopin’s part. It’s important for smart people to have non-intellectual experiences, because too much thinking can be seriously maladaptive, (Imagine the stereotypical high school “nerd” character who can answer any math question but can barely function in social situations). For me, that’s why I like being a musician as opposed to, say, a writer. Classical music is ridiculously thoughtful, but there’s an athletic aspect to it, and sometimes the senses are allowed to usurp the thinking mind, as in the “effervescent waltz” part of the Brahms sonata you wrote about some posts back. From his extreme sensuality to his avoidance of extra-pianistic composition, I’ve come to think of Chopin as maybe political, or at least passive-aggressive, but certainly opposed to the forces of domineering intellectualism.

The polonaise-fantasie is a really good example of (bringin’ in Susan McClary) a slightly more feminist-y approach. To me, it is largely about overcoming perfectionism, what with the slightly-dissatisfied-but-stoic ending, and the monumental final restatement of the b-major theme in a-flat, which I think of (why do I have a feeling you will resent this characterization?) as skipping… with abandon. But no, I don’t think that Chopin’s sensuality makes him any less of a guiding light than Schubert in all his structure.

Thanks for giving me a space to vent my nerdy music thoughts. I am glad that you sound well, and are playing this piece.

Nate

Nicely put. I have friends with the same attitude (they can’t help it, having studied music at universities in the 80s), but haven’t been able to find the words to to properly stand up for Chopin and how his music moves me.

. . . except that my brain, etched with 3rd Ballade practice from college days, starts playing lilting Ab octaves to my mind’s ear after that last chord’s been held a while. Oliver Sacks, make it stop.

The richness of expression, ‘classical’ in the sense that it is so rich that one never tires of repeated hearings over many years. As a player, I notice the supreme ‘craft’, the voicings that are exactly suited to their moments, that amplify the meaning of the moment and the context. Craft in the avoidance of literal repetition. My visual equivalent is a perfectly tailored suit of clothes.

Since my passion for Classical (of all centuries) is a fairly solitary pursuit, I would tend to not be terribly swayed by dismissals of music I find compelling.

Thanks for your insights, Jeremy, some day I’ll hear you live, I look forward to it.

If we only had all that or even a little in

the

world of violin music .!!!!!

Education does wonders for such people.

Ballade No. 4 in F minor, Op. 52. Enough said.

Dear Jeremy:

I look forward to your concert tonight in Finney Chapel with Joshua Bell.

I love reading your musings that combine a reverence for our beloved music with hilarious jabs at the comparative paltriness of modern pop culture. I also relish your use of audio and video examples to bring your points home.

I have always loved the Polonaise-fantaisie, its ambiguity and anguished search for identity–I feel this is a paean to the fate of the expatriate who is forever pining for the homeland, while knowing that there can be no return. At the risk of ruining the piece forever, I imagine the words “ma patrie!” (and, later, “oh, ma patrie!”) set to the heart-wrenching F#-G# melody in the B major section.

One small correction: in the passage introducing the solemn B major chorale, surely you mean E# and not F# as the salient pitch in the suspenseful chord awaiting resolution.

Thanks again for the stimulating essays.

Warmly,

Peter Takács (Bibbins 331)

Chopin’s music was certainly not dumb or boring. His music might be boring to those that desire a showy and bold exposition of thought or feeling. But (to use your very accurate description of the man’s character) “Chopin’s vast refinement of thought and elegance and culture” requires a similar personality in the listener for his music to be appreciated and understood. Or, at least a listener with great powers of empathy and understanding. Those who label his music as boring haven’t the “refined and elegant” brand of thought required to understand him, IMHO.

You’ve done a great job of displaying the intimate message and even the pathos inherent in his Polonaise-Fantasie. I have always liked what the biographer Huneker said of Chopin’s music – “Chopin’s arrows are tipped in fire, but they do not travel very far.”

Cheers!

LOVE the way you write. I’ve missed reading you. Classical Music blogs have so depressed me I quit reading for awhile.

Thanks for brightening my day.

(I think Chopin is Blake smart and Turkish Diplomat savvy…..and passive aggressive as hell)

Thank you for your wonderful thoughts through this blog. And thank you for the incredible playing of Bach, Ives, Chopin and Schumann last night, in Seattle. I’ve never cared for Schumann very much before, but while you were knocking my socks off with the Ives I smiled to myself and figured you’d probably make me like the Schumann waltzes. Your playing woke me up to them. I’ve never been ashamed that I liked Chopin. Since my teens I’ve listened to him and just assumed that someone else was unlucky if they didn’t hear what I heard. Glad you agree. And I cut my teeth on Bach and Stravinsky.

Hello, I found your website while doing some research and thought I’d share some information with you in the hope that it might of of interest to you and others reading this terrific blog. I decided recently to upload to YouTube the “Dziela Wszystkie” series of Chopin’s works (about 25 LPs) that was produced by Polskie Nagrania in 1959-1960. Artists include such Polish luminaries as Boleslaw Woytowicz, W?adys?aw K?dra, Jan Ekier, Lidia Grychto?ówna, Halina Czerny Stefanska, Henryk Sztompka and the great pedagogue Zbigniew Drzewiecki. I am sharing this information because I regard the contributions by these and other Polish artists of the early 20th century to be of great importance; additionally, I understand that these recordings cannot be found anywhere else on the internet. There are several playlists that can be reviewed; I am providing a sampling below, with links. kind regards, david hertzberg

Boleslaw Woytowicz play the complete Etudes here:

http://www.youtube.com/my_playlists?p=F5920B7B5FBB1DEE

Henryk Sztompka, the complete Mazurkas, here:

http://www.youtube.com/my_playlists?p=55ADC0D965C07EB7

Zbigniew Drzewiecki, a handful of nocturnes, here:

http://www.youtube.com/my_playlists?p=762F9BDAF45F63B4

And W?adys?aw Szpilman, Tadeusz Wro?ski, and Aleksander Ciechanski performing most of the chamber music of Chopin here:

http://www.youtube.com/my_playlists?p=A198C1B1D4DA83F4

Brilliant stuff. People who see Chopin as writing w/ a “pen dipped in moonlight” miss the poise and classical restraint.

4 Trackbacks

[…] have as their base utterly simple structures. (For example, read Jeremy Denk’s eloquent analysis of some genius-transformed simplicities in Chopin—and while you’re there, look at the […]

[…] Denk offers a delicious walk through Chopin’s […]

[…] kirjoituksissa, joissa Denk panee likoon tietonsa ja taitonsa: yllä oleva lainaus on Frédéric Chopinin Poloneesi-fantasiaa Op. 61 käsittelevästä esseestä, jossa kotipianolla välittömän tuntuisesti soitettujen esimerkkien ohella on kiinnostavaa, […]

[…] he had an entry on Chopin:[link to blog]. It was his musings that got me thinking about why I like Chopin again and playing and […]