Airport, luggage, dawn. Desolate lanes of structure, sleeping planes like sorrowful birds, vans vrooming out of the darkness towards lonely kiosks. I boarded the bus. I had just settled myself in my seat, when a woman deposited two two-year-old boys opposite me: they swayed there, it seemed to me, like two jiggly jello molds. Aww. Casting occasional coos at them, the mother de-and-re-boarded many times, for toddler equipment … the kind of equipment you’d need a congressional appropriations bill for … carseats, strollers, baby duffels, tripods, a gross of Ziploc bags, do I see riot gear? I watched and watched. But while executing this cargo transfer, she found time to deposit with each boy a small stuffed dog, saying …

“…here’s your puppy …”

and a small container, saying …

“…here’s your sippy …”

The boys each seemed to magnetize around their puppies and sippies, and slowed their jiggling, like planets held in place by dual suns. I was instantly swept by waves of envy. Where’s MY sippy, dammit? Where is my metaphorical mommy to give my sippy for playing my Schubert Sonata a few days ago? The piece is a &*()#$ hour long and I don’t get a sippy? Here, here, on the airport bus, of all places, I need my sippy, and not some faceless wakeup call from a stoned clerk, or some crappy Cobb salad, or minibar jelly beans ($7.95!). I looked down at my fist. My clenched, desperate cup of coffee was there. What a sour, sad sippy it seemed, alas.

The last person to get on the plane sat next to lucky me. He was the window to my aisle, a tall lunk of a lad, and he casually sported a sweatsuit that was disintegrating at its edges, into threads that swept like a bead curtain over my face as he swung over me, smelling of nervous stomach. He said, by way of greeting,

“I’ve got movies.”

Trouble, I thought. As I parsed this statement and its implications of excessive friendliness, he called the passing stewardess over:

“I have an anxiety problem.”

“Yes,” she replied, serenely.

“And listen, I really don’t like flying, and I’m just really nervous.”

“Everything will be fine. Just relax.”

And this genius of customer relations walked away and he kind of trembled and swayed and gulped and I was left there with my rowmate and his movies. It was my job to do something, to prevent a full-blown freakout … (where is my sippy) … and I realized that this, THIS, was my heroic moment, that I had to be the brave sippy to his lunky puppy! Ahem, I said. This is an easy flight and I take it all the time! I fluttered by him all my horrible pretentious expertise about flying, all that well-traveled ‘tude, bravado all to make him happy and I told him (become the cheerleader you’ve always wanted to be, Jeremy!) yes I LOVE movies and I’d enjoy peering over at the screen to peep soundlessly on whatever movie you want to watch … I was groggily heroic and stoic and zzzzz.

Some of my jellybeans spilled.

The plane took off. The ground receded into misty morning distance, far from buses and lanes. “Is it normal, for the plane to go up like this?” he asked nervously.

I didn’t exactly know what to say.

And then there ensued that amazing mostly monologue of the Person From The Midwest Who Has Never Been To New York Getting All Excited About Coming To The Big City And Asking You What To Do But Looking Extremely Dubious and Bored About Any Suggestions You Give Him For Enjoying It. Finally I was in the taxi and against all expectations my luggage was in the backseat with me, turning into a giant alligator and it began hissing at me louder and louder about ssssssssss … sir you have to wake up now we are at your apartment, the maniacal driver said. And in my clean apartment I watched everything do nothing for a while. And I thought about that Schubert B-flat Sonata.

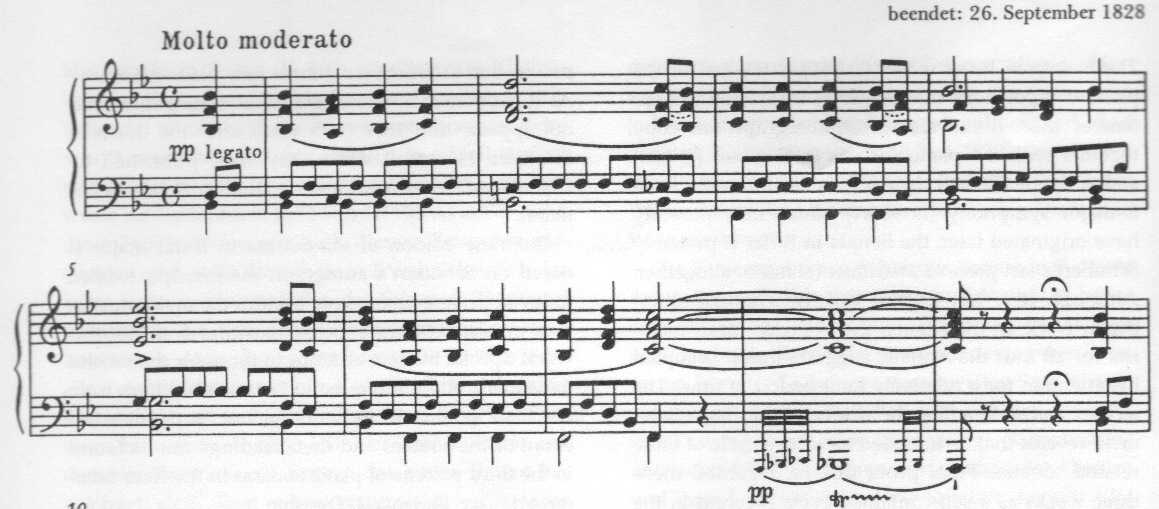

First, there is the folksong. I actually can’t tell you why, while practicing this piece over the last weeks, I kept thinking folksong, folksong … maybe it had something to do with Ives or Bartok or with my need to get back to the people or a vitamin deficiency. But the more you look at the tune, the more you wonder about it, and of course the famous half-cadence at the end with the famous trill

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… of course, of course. (A little note to all of you who freak out every time I begin to mention terms like “half-cadence”: don’t freak out, everything will be OK, do you need a sippy? Look it up on Wikipedia or something. Jeez.) Now, it seems to me that this melody, that this opening of the Sonata, perfectly represents something Schubert did that Beethoven was more or less incapable of doing: that is, patting his head while rubbing his tummy.

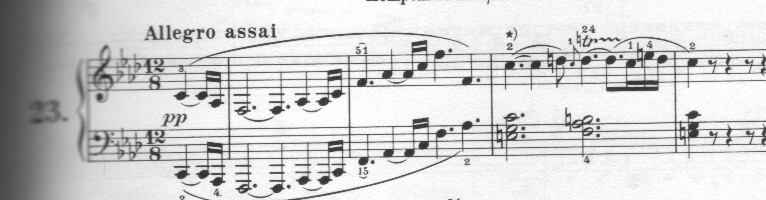

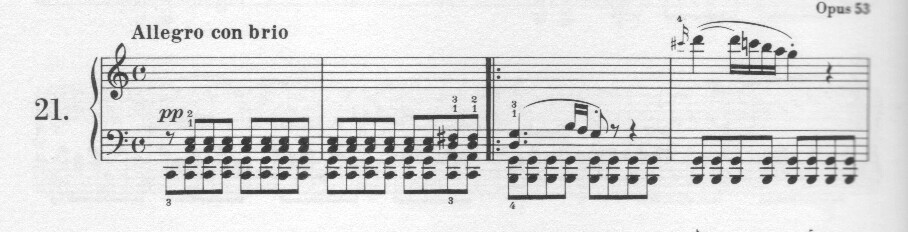

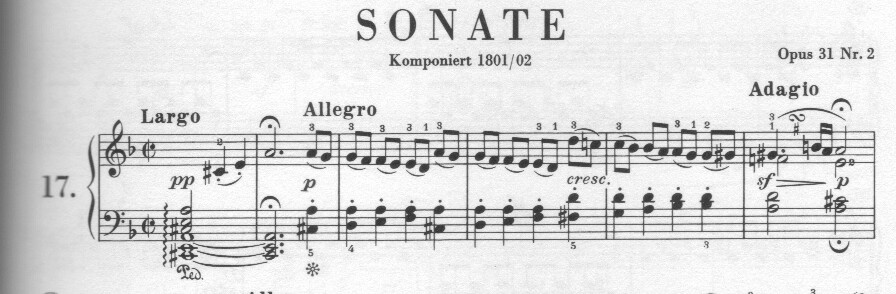

If you think of Beethoven openings

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… dramatic, tragic, rhythmic … or

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… suspenseful, waiting to explode … or

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… joyful bounding quiet energy waiting to explode … or even

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Beethoven openings can be conflicted consecutively, but not simultaneously. There can be tit-for-tat, but rarely (if ever) tit/tat. In this wonderful opening of the “Tempest,” there is the mysterious arpeggio, promising unanswered questions till the cows come home, and then there is the agitato, Allegro reply which doesn’t find much satisfaction either (neither urgency nor patience are rewarded) … but, you see, these are two characters in dialogue and not one really screwed-up schizophrenic (no offense to you schizophrenics, I love you all). In Beethoven, conflicts arise in the narrative but are not woven into the DNA; they are not inoperable tumors of meaning. They arise from tendencies within the musical “characters” (as in classic Greek tragedy) which inevitably lead to conflicts: but these Beethoven characters are good solid movers and shakers. They at least have tendencies, and are not prone to strange loops of self-deception and doubt. They need anger management, maybe, but not Zoloft.

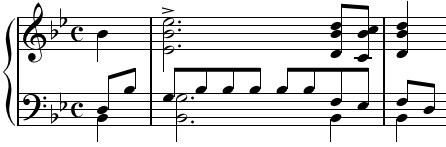

Schubert’s tunes are made to reflect upon themselves, doubtfully. Also they draw so much more deeply upon cliché, upon signifiers of folk style, which are lingering around them, casting webs of (often sad) association. These webs of association may be part of Schubert’s special compositional “problem.” It makes his music feel less divorced from the world, more prone to weakness. When Schubert writes a little mini plagal cadence at the end of the first phrase …

and then immediately begins the second, strikingly, by lifting himself up to the same harmony at length …

Well, this is the perfect example of what I mean. The plagal is a cliché, coloring the end of the first phrase, a beautiful but hackneyed detail; but the clincher is the subsequent elevation and reinterpretation of this cliché, held up there for for three beats while you listen to the aching quality of the subdominant (despite its past prosaic identity). No, stop, it’s a cliché, you say, but why is it so beautiful?

Yes, that is one thing about Schubert: the musical cliché within, and without; as detail and suddenly in your face; moved from inner voice to outer, and no one, but no one, understood voicing better than Schubert. This revoicing is the eruption of the inner world … only what’s inside is old news, a torn worn keepsake.

Back to the main thesis: Schubert has managed to do two things at once. He has written a beautiful, lyrical, pastoral melody, and at the same time has removed some element of naturalness or some urge from this melody, from this genre, from this world. He has imposed some other voice which says not so fast or simply but or why. Not the florid, surging, questing why of Schumann’s “Warum?” but a darker, bleaker why. The trill is the final, coalescing materialization of this unease or malaise hiding behind the melody, but it is not (in my opinion) its first appearance. In the same way that Beckett, for instance, will begin a novel by tearing apart the justification for writing at all …

I am in my mother’s room. It’s I who live there now. I don’t know how I got there. Perhaps in an ambulance, certainly a vehicle of some kind. I was helped. I’d never have got there alone. There’s this man who comes every week. Perhaps I got here thanks to him. He says not. He gives me money and takes away the pages. So many pages, so much money. Yes, i work now, a little like I used to, except that I don’t know how to work any more. That doesn’t matter apparently. What I’d like now is to speak of the things that are left, say my goodbyes, finish dying. They don’t want that.

… so Schubert begins by writing the folksong that is expected of him and yet, perhaps, his heart is not in it. To that end, I feel that the most chilling moment of this tune is not when the trill (death?) appears, but just before: just the beat where the dominant chord is sitting there, alone, without a bass, abandoned, waiting.

God, I’m suddenly really pissed at myself, calling the trill death, even in parentheses. It just smacks of too-easy equivalence and New Musicology, etc. etc., short-circuiting Schubert’s meaning, making it all Lifetime Movie. How you “understand” the trill may be so important to the movement, and calling it death is–let’s face it–kind of a cheap out. Ack. It may make the audience ooh and aah, but are those really the oohs and aahs we want?

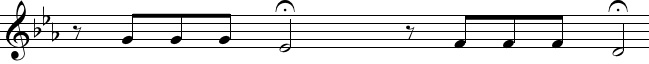

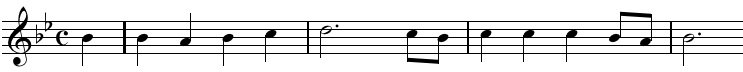

To think of it another way, look at the contour of the main melody …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… Now, part of what makes this theme seem as though its “heart is not in it” is the way it circles around its very limited space. (Charles Rosen wrote the definitive article on this somewhere or other, but I’m too lazy to look it up … something about the gradual expansion of melodic space in Schubert.) It circles around its room of tones, not exactly looking for a way out; however, we as listeners may feel the absence of drive or will. We may feel the room’s limiting presence without exactly knowing it’s there.

Compare, perhaps, to the opening of the Archduke Trio …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

It seems fairly clear to me that Schubert’s melody is based upon Beethoven’s, but the intervals have merely been flattened out. Both themes are “about” the subdominant though (or you could say they are vehicles for, or toward, the beauty of the subdominant) and dwell on it before leaving for a half cadence. Compare Beethoven’s ecstatic half cadence with Schubert’s haunting half-cadence. There you go; that’s all you really need to get, to understand the “relationship” between these two pieces. It is the Archduke Trio theme, deflated and purged … without directionality, or with only the hint of directionality, with remnants of purpose, or question marks over its purposes. In Schubert I hear the simultaneous expression of something and the sadness of having to say it. The Archduke is not sad about what it has to say, no, no.

Now look back at the main melody contour … and now compare that to the little “event” of the trill:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The main melody essentially travels Bb-C-D-C-Bb, up a third and down, and so too the trill (F-Gb-Ab-Gb-F). These two circling movements are the same sort of thing, but at two different layers, and in two different modes. This combination of resemblance and dissonance is disturbing. There is a kind of grinding of layers against each other, a tectonic meaning-grinding, a deep-seated ambivalence. And after all it is just a folksong, right? (Right.) For me the trill is not death but this terrifying ambivalence, the darkest possible manifestation of the question mark of the half-cadence, the perfectly wrong thing. While the melody attempts to sing us into a certain space, the trill questions the existence of the space itself.

I don’t think Beethoven ever wrote anything as disturbing as this folksong with the bass trill undertone, its cousin and its existential nemesis. Beethoven, clearly, had his sippy, but Schubert … Even comfort is uncomfortable to him.

26 Comments

The bass trill has never said “death to me.

It’s more like the voice of reality intruding on a dream.

As in “I wish I were Beethoven, but alas, I am only Schubert”

I’m still pondering my “response” to “Schubertt (sic)”, but, in the meantime.. I hope Ives and his “family” are behaving tonight in Seattle. -Although, I guess a little misbehavior would not be uncalled for; rather, it would be expected, almost natural.

This is not a reply to your informative entry about Schubert, but the space I found to express my enthusiasm for your performance of Ives’ Sonata No. 1 last night at Lakeside. It was fantastic (I only wish you’d had more time for your introductory comments – which are always so helpful and engaging).

What surprised me most was how reminiscent the Ives piece was of Berg’s Opus 1 – in tonality (very similar choices chordal choices, especially in Ives’ first movement), similar textures and resolutions of dissonance, etc.

“Reminiscent” is probably the wrong word since they were contemporaneous. I came home to find online that they were both written at essentially the same time (1909). I wonder if Ives & Berg knew much of one another. It has always seemed unfortunate to me that too little credit is given to these two pivotal pieces.

While we’re expropriating Schubert’s and Schumann’s blogspace, Mr. Denk, do you happen to know Schumann’s “Die Rose Stand Im Thau” – a wonderous short a cappella piece for 5 male parts (Choral SATB, with baritone solo)? This is another of those surprising, really breathtaking but little known works — one that came to mind as I read your comments about “folksong, folksong”

Loved the Ives last night.

Thanks for bringing John Cleese and Marcel Proust into the mix.

Looking forward to more as the festival progresses.

You’re regular Beckett quotes in your occasional postings continue to make my day every time. Now, quickly, relate How It Is to the third Boulez sonata!

The trill is especially ominous for me because it is saying “You love this trill. And that’s why you’re going to play the exposition repeat, because otherwise you don’t get to hear it come back fortissimo right before the repeat. I don’t care HOW long the sonata is…”.

In some ways, the way in which the opening theme is not really allowed to finish in a satisfying way (at first) reminds me of quite a few of Mozart’s slow movements. It feels as though he hasn’t earned that real resolution yet, and that he’s going to have to work through some issues before he can really give that theme a proper ending. Compare for instance the slow movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto #17 in G. The Mozart doesn’t quite have the “folksy” quality, but it has a similar effect.

Also worth pointing out that sudden shift into G-flat after another run through of the opening theme. That sort of feeling like you’ve just walked through some sort of arch into a garden is something Schubert pulls off better than just about anyone. And it’s elegantly effective piano writing, as well.

“Now, it seems to me that this melody, that this opening of the Sonata, perfectly represents something Schubert did that Beethoven was more or less incapable of doing: that is, patting his head while rubbing his tummy.”

–hilarious and fabulously informative, as always

LOL!

And here I thought classical musicians were boring:)

Well, they kind of are

-your technical disputes are way over my head-

But your writing skills are impressive…down-to-earth, yet intellectually in the clouds.

I’m not a writer, so not a huge compliment:):)

Anyway, I enjoyed reading about your observations:)

Just an FYI-sippy cups are gross..slimy, germy..I only give children sanitized sippy cups. 2 is a very fun and cute age:):) I wonder if she gave them a sedative, though?

🙂

Absolutely LOVE reading your blog. Have just discovered it and then just *had* to start reading from the start in 2005. What a mavel you are to get it all so squirmingly well into words! Fabulouso, dude, seriously. :>) J.

Just want to let you know how much I enjoy your observations both of life and music! Your Schubert/Beethoven insights rock.

I fell in love with this sonata after watching Bruno Monsaingeon’s documentary on ‘Richter: The Enigma’ – the film opens and closes with it. And now i’m listening to a live recording of Richter playing it in some parish church in England. It’s a terrible recording in that there’s all sorts of awful ambient noise – audience members coughing, cars, apparently even airplanes, according to the CD liner notes – but Richter plays oh so beautifully. i think i’m gonna be obsessing over this sonata for quite some time now.

I fell in love with this sonata when I was 4. In my nursery school, while we napped, they played us a record about little mice that came out at night and played a child’s toy piano. The mice played just the opening phrase, and I adored it, but I couldn’t sing it well enough for my parents to identify. So it took me years to find out what the mice were playing, and finally hear the rest of the piece.

What a piece. Loved Mr. Denk’s performance. I wish him all the fortune in the world in his search for (or not) the sippy, and maybe even the puppy.

What pensive mice! You’d expect normal mice to play something more along the lines of…. oh i dunno… Quick, people, what would normal mice play?

“What a Friend We Have in Cheeses,” perhaps?

I agree, that Schubert trill isn’t death. It’s a reminder of life… and how short life is [which refers less to imminent death than to an appreciation for NOW, knowing that LATER may not be available, due to unforeseen circumstances ranging from Limited Time Only sales, to pesky 24-hour food poisoning to… uh… yup, death]. That trill causes us to snap out of the complacency of the beautiful calmness of everyday melody and ease and remember that indeed our Ease… and F’s and G’s… are not infinite.

There’s a moment in a Mendelssohn piece I play that hits me similarly: Book 1 of “Songs Without Words,” Number 2. The music is in A minor, so hey, we’re already in a pensive place at note one. But he keeps the tessitura pretty high through the three page ditty until Wham!, the Coda adds a low octave and then Double-Wham!, suddenly 12 bars from the end he has instantly plummeted us to a dark, dank, dissonant basement of remorse, one step away from downing too many little pink pills. Whoa! How did we get here?? No one sees it coming. Not even me after playing it over a gazillion years. It kills me every time. Nice to have those life reminders.

Break a leg tonight at Mostly Mozart (where you will be playing Solely Schubert).

Well, I have to say, you played the piece tonight perhaps even as movingly as the little mice. If your performance stays with me as long as theirs did–and I have every reason to think it will–this night will still be haunting me when I’m 88!

Great post! I love the way you write.

I am that mother (well not that one exactly) an I am glad to know that I make someone miss their mom…

dear jeremey,

it’s been almost 2 months since your last post. not that posting to your blog is a necessity, but i do miss you so. any chance for even a one-liner to tide me over?

hugs, claire

p.s. here’s your sippy. 🙂

Ok, now I know the need for the sippy but what about the puppy? Was it just dragged by a paw to follow, like an afterthought?

The trill sounds to me like a variant thought, an interference in the mind, the intrusion one needs to push aside for the time being until the current, more pleasant task is complete.

Thanks for your very educational, pondering and always entertaining column. I enjoy listening to you whenever I can when you play here in the City by the Bay.

I second Claire …. we miss you …. I know you need to practice (and so do I) … but pleeeeease?? Just a little ditti between scales ….

Have you ever heard of classical pianist Ronnie

Segev? He’s a brilliant artist. If you aren’t familiar with who he is, he has this organization: Ronnie Segev’s TOC that donates music lessons and instruments to kids in need. He also plays around New York

City… I found his Ronnie Segev’s schedule online.

I was googling around and doing some research on him. I found out that he has these Ronnie Segev’s music salons where you can actually go over to his place and listen to a bunch of people try out their piano music ( singing, violin, etc) on one another. He’s got an IMDB to: Ronnie Segev’s IBDB page I’m just full of useful info 😉 E-mail me if you are interested in more information. I happen to be a pretty big fan and wanted to know if you have heard of him.

I heard your Ives/Beethoven performance in Amherst, MA, (BRAVO!!) and spoke with you after the concert. I have been following your reviews from Boston to New York – if YOU had any doubts about the program and performance, surely they have been dispelled. What I heard is still fresh in my ears. Thank you, so very much.

Mr. Denk (or may I call you Jeremy?), this is one of the most brilliant and enjoyable things I’ve read in a long, long time. I’m a conservatory violinist currently suffering from a combo of end-of-semester burnout and a bad case of “is this all there is?” This piece of writing not only made my day, but gave me a much-needed look again at what I love about classical music, the combination of intellect and emotion so perfectly balanced, the mathematical/logical theories and their sheer literary context. OK enough of my futile grasping for pretentious academia-speak, just a big thank you! I’ve just discovered your blog and I’m utterly delighted by everything i’ve read so far here. 🙂

Hey Jeremy. I’m going back through some of your older posts. (Hint. Just kidding.)

I appreciate your notes about Schubert’s “chichéd” themes. I spent about 10 minutes last summer trying to explain the last movement of D.840 to my saxophonist-friend. “Yes, it’s an overly simplistic melody, almost boring, but that’s precisely WHY it’s interesting,” I said, (but without using the word “precisely.”) “It’s almost like a commentary on absent-mindedness. Thinking about thinking. It’s cool, it’s crazy…” Needless to say, my eloquence did not convert him. Some people don’t like Schubert, either because they miss the depth of his apparently clichéd themes, or because they are irritated and unsettled by his tendency to plunge into circles of questioning, self-referential thought. But, like you, I find these wanderings intriguing, resonant with the way my mind works; they draw me into a personal, shifting and magical musical landscape that often affects me more deeply than Beethoven.

So I disagree with the spirit of the first comment; I am incredibly glad that Schubert was himself and not another Beethoven. But I wonder if Schubert ever tried to be “more than himself?” Probably, given his capacity to doubt. I play the second half of the first theme almost as if Schubert is lunging (albiet delicately) for, perhaps even forcing a resolution. The first half of the folksong theme is followed by a plagal cadence (E-flat – B-flat), “Amen,” thereby consecrating it. Then Schubert moves to E-flat, considering the cliché he just created, but where to go from there? The rest of the phrase does indeed seem haunted by uncertainty, as if Schubert is using rote melodic logic to try to create an appropriate counter statement to the first, sacred part of the phrase. Then, we have the half cadence, which is actually another plagal cadence, this time of the fifth (B-flat – F), Schubert asking, “And this part of the phrase is sacred too, right?” The bass answers…

My favorite moment in this piece is in the recapitulation, when Schubert leaves the part of the Sonata you discussed in this blog, modulating into G-flat, then, tragically, F-sharp minor. His doubts, his questioning, precipitate a storm in the development and this modulation is the scar of that experience. But then, the bass steps up to A, and suddenly we are in D major. It is a beautiful moment, holistic and healing. All the suffering in the sonata has led, unexpectedly, to a new and beautiful key. And the beauty is not shining through in spite of the pieces flaws, but it is there because of them: without F-sharp minor we would not have reached D. And at the end of the movement, he restates the first theme, but only the first part, once as before, then pushed up a third as if admiring it from a different angle, and then back to the first position. He seems to say, “If only the first part of my phrase is sacred, than that is all I need. I won’t try to be Beethoven by lunging after a single drawn-out idea, a single unsullied character. ” And, to validate his trepidatious journey, the rumbling bass trill remains. Even though he has rejected all but the first wisps of the Sonata he recognizes that this doubt, the driving force, may be less his enemy than he thought.

I played the first movement the summer after leaving Bard. I think it helped me, and it means a lot to me. Although I played it with feeling and some degree of understanding, and have thought about it a quite a lot, there are stilll huge chunks of it that elude me, to the point that I have begun to feel that I “failed” to interpret the piece. Reading this post has reinvigorated me, and makes me really wish that I had played some Schubert at Bard.

I hope you don’t mind me leaving long comments like this one. But the ensuing comments and occasional debate are half the fun of your blogs (Well, more like three eighths of the fun…)

One Trackback

[…] Denkin aiemmista tuotoksista kannattaa lukea myös Schubertin suurta B-duuri- tai Charles Ivesin Concord-sonaattia koskevat […]