Situation 1.

I decide to get a Rice Krispie Treat. Sitting at home, stationary at my table, I decide that it would be supremely delicious just then, just now, to have a Rice Krispie Treat. So I put on my coat, slip shoes over socks, wrap a scarf neckwise, check wallet pocketwise, keys likewise, and head out the door, through elevator through lobby, to and up Broadway, and thus walk into Starbucks with the full intention of purchasing and eating a Rice Krispie Treat, an intention which I realize and enjoy munchingly on my way home, with occasional straggling Krispies trailing behind me like fairy dust.

There is not a trace of Treat left when I open my door on the return trip.

Situation 2.

I am just walking, admiring, living, squinting. Wind blows about me and cools the sun and I admire many scarves about me, as I do not have a scarf. Broadway is a maze of conflicting people, I move left and right and left. When will I go to sleep?, I wonder, how should I live the rest of this day or life?, I wonder, etc. etc. At a crucial moment (it doesn’t matter when, however), my eye catches sight of a Starbucks. I enter, not knowing what it is, other than nothing, that I want from it. At a subsequently crucial moment (also irrelevant), my eye through the glass case catches sight of a Rice Krispie Treat, traipsing amongst many other treats.

Suddenly—at that irrelevant moment—I want nothing more than a Rice Krispie Treat, nothing at all more. I purchase it, at the very next moment possible; I eat it, at the very next moment possible after that.

Situation 3.

I am anywhere in the space-time continuum, anywhere at all. I might be picking my nose, for all you care, or I might be practicing Beethoven. What matters is that my mouth, at that moment, is not occupied with any particular thing or activity. (You will soon see why.) So, again—at the risk of being tiresome!—visualize me anywhere with an unused, but not unusable, mouth. Suddenly, a Rice Krispie Treat appears, at least partly protruding into my mouth in an edible manner. It does not fill my mouth, as that would be uncomfortable, but it wishes to do so, or I wish it to do so, or some combination thereof. I am overcome with pleasure at the Treat’s appearance, though shocked and perhaps borderline disturbed. I have no idea why or how the Treat appeared, but there may well be hidden mechanisms by which the Treat came to my mouth or my mouth to it.

The Treat is eaten, with love and surprise.

——

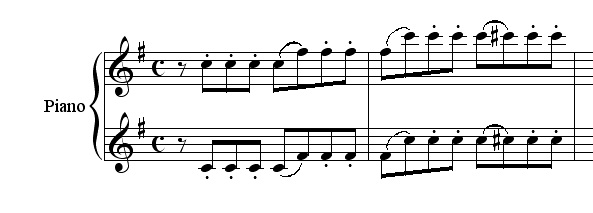

Throw away all your music theory textbooks. (Applause.) Better yet, put them through the shredder, so no one can reclaim them. I would suggest, in their stead, that virtually all moments in music are either Situation 1, Situation 2, or Situation 3. Those moments that are none of the above are probably not worth mentioning. For my first example, here’s a Situation 3:

Recapitulation of Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2, first movement

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

[Barenboim, Barbirolli. Krispie arrives towards end, of course. Like many great artists who have taken on this piece, Barenboim and Barbirolli feel that the Krispie moment requires slowage. This is a perfectly reasonable, but debatable point. I personally munch my Krispies quite quickly, as has been said, which is irrelevant. I love this performance, but could be the devil’s advocate and imagine a more surprising Krispie, with the piano remaining more of a angelic shimmer, remaining more in the dark of the horn’s arrival. Nonetheless it is still a beautiful beloved Barenboim Krispie.]

Right! See, so if one of the greatest moments in music can be described perfectly with my method, my method must be the only correct method. (I got this line of reasoning from Schenker, I’ll admit.) Do I really need further examples? The Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde: definitely Situation 1. Wagner decided to get the treat in the Prelude, while sitting, quite stationarily (or at least very slowly) at the table of infinite ambiguity, and clearly the rest of the opera is merely the donning of a potion coat, a pass through the lobby of love at dawn, a sail up Broadway to Starbucks with armies of shoes and scarves, etc. and when you return home, there is nothing left: love (treat) brings death. I have always associated Rice Krispies with B major, all other things being equal.

So far, I have no examples for Situation 2. But I’m sure they’re out there. Anyone who submits a complete analysis of a movement of Mozart using the Rice Krispie Treat method gets my undying love and devotion (whatever that means)—especially if they include Situation 2.

Let’s get Serious, Now.

I suppose, if there must be a serious point to all this—and I kind of wish there weren’t—that situations 1-3 are “about” various degrees of will and desire. Will is not either free or not. The Krispie Method shows that I might succumb to desire with various amounts of will, and posits a kind of will-free extreme, where the Treat appears out of nowhere, is not willed and yet is extremely desired: probably impossible, probably heaven. Music has a way of evoking these various states of will.

Self-promotional sentence: Last month I played Beethoven 4th and 5th Concertos. Along the way, somewhere, unwilled, like a treat out of nowhere, it began to strike me that one of those pieces was more “willed” than the other, and that this contrast is interesting, beautiful, a path (for me) into some new framework of light and shade. One concerto is determined and the other is willful, like a child. The 5th is the adult who decides and the 4th is the child who wonders and both are tremendous—but all things being equal, I probably enjoy a bit less will.

It struck me that one of the recurring, characteristic, marvelous gestures of the 4th Concerto is this: sending a note up, to see what will happen to it. Notes are left, for periods of time, to fend for themselves. This is very different from arranging your notes’ flights first, reserving hotels, etc. Luckily the notes of the 4th Concerto know what do with their free time. Put another way, the notes of the 4th might need a manager, but get by with inspiration and beauty, like so many people on Earth.

When the piano enters after the tutti in the 5th Concerto, it does so with two bars of chromatic scales on the dominant, landing on the tonic, rather neatly, and tidily, like it knew all along that the tonic was coming, or that it wanted a Krispie (yes, do you get the ANALOGY now?, or do you need a hammer?); the piano’s appearance is the rectification of the enigma of the orchestra’s previous notes, zipping things into place. The theme reappears; whew, it is beautiful.

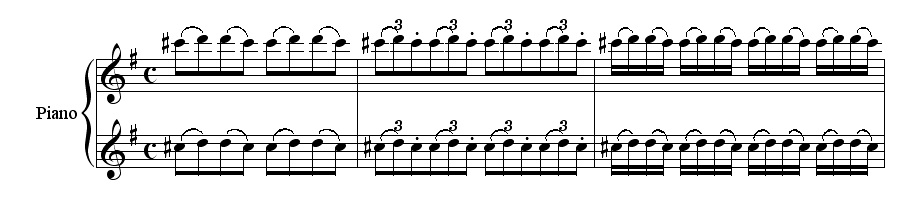

But in the parallel spot in the 4th Concerto, the piano’s entrance (its escape from the tutti) is much less “efficient,” much more roundabout. The pianist begins on the 7th of the dominant (rather than the more neutral 3rd) and does everything to emphasize, to taste, the awkward tritones hiding in the chord. The pianist wants us to know that there are ugly/beautiful intervals hidden in the common sounds, like trolls in the forest. The piano makes the arpeggiation the opposite of tidy, somewhat painstaking, even a bit flirtatious? …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

There is no urgency to this upward motion. In fact, it is the opposite of urgency: a playful extenuation, for its own charming sake!, of the upward motion, a teasing gradualness (an intervallic striptease). And instead of a beeline for the tonic, there is a delicious teetering, a tottering, a wavering in the wind, a roulette ball choosing between C# and D:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… after which, like a ball released, the notes fall and reascend with tremendous speed, landing once more on a trill which seems to affirm that D is really really really (promise!) the note we want! … (though the trill itself seems to suggest unspent energies)…

And under this trill, for me, the most hilarious, or the most charming, note: a mere, plucked G. Pluck, the orchestra says. Tonic, the orchestra says. As if to arrest the motion of the piano, to hold the trilling hummingbird in hand. But this pluck or tonic does not coincide with either the beginning of the trill nor its end, it is a boundary without anything to bound. The piano only agrees, perhaps, insofar as it is willing to begin a new idea which modulates from tonic to dominant, but then it is willing to head back to the tonic and then back to the dominant… it is terribly willing, but not subject to a single will. Haha, the piano says, I will wander, and when I am ready I will let you get back to business.

The composer, seemingly, relinquishes his will to the caprice of the pianist. The pianist has decided on a sweet snack, but as so often the consideration, the expectant caress of the Krispie transcends its consumption. A dance, a play around will, with decision waiting in the wings like a spurned lover. (Except there is no spurned love in the 4th.)

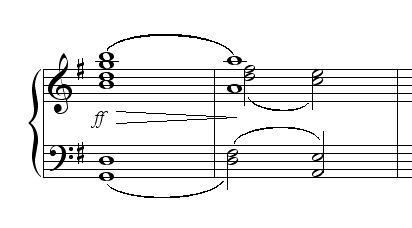

Another absolutely characteristic, fantastic, recurring gesture of the 4th Concerto is what you might call the reverse resolution … a movement downward in the bass by fourth, from a tonic to its dominant. A subsequent acceptance that the dominant is now the tonic and the tonic-which-was-the-tonic is now the dominant, an acceptance that is a kind of relinquishing. Suppose we say that the movement dominant-tonic, V-I, a most fundamental harmonic unit, is a kind of emblem of decision: a resolution: we are here, now! But I-V discovers the tonic (which is, in fact, a new tonic) a different way: we are here, now?, with a question mark that only with time crystallizes into a period.

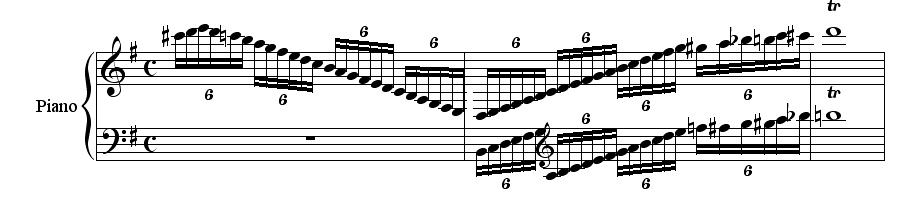

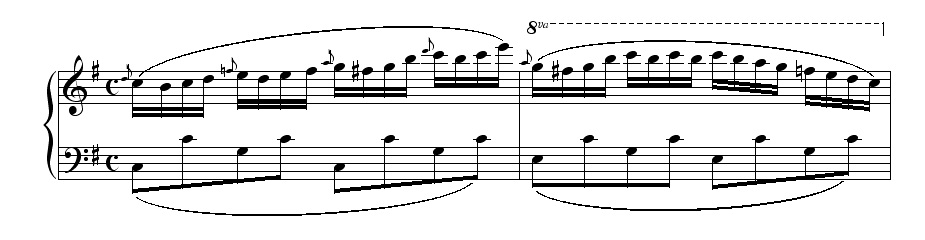

And in the most wonderful instances of this idea, Beethoven does a double whammy:

Though often the first I-V (G-D) sounds well enough, means plenty in performance, often the stunning second, unexpected, inward step (D to A minor) is not “noticed” well enough, not seen in its truly radical introversion. This downward two-step radiation by fourth G-D-A is a fissure beneath the surface of the piece, a release, a relinquishing, an Anti-Modulation, which nonetheless takes us to the key of the closing theme, a quick relinquishing—so quick! so sudden!—without which the piece would accomplish nothing, would get nowhere. If dominant to tonic is an act of will, tonic to dominant is anti-will, though the opposite of will is not necessarily total passivity, or a lack foremost; it is a field of motion in which events proceed differently, as if of their own accord, almost as if in some cases the composer has a will and in others the notes have a will of their own.

And some of the most astounding beauties of the 4th Concerto have to do with the calibration of the imposition of will. The timing of the emergence of decision and desire. For example…

Whenever I play this passage …

I have the feeling I am free, playing let’s say in some sort of garden. (Situation 3, perhaps.) I know this is a very specific, random image, just one of many possible, but it keeps coming to me there, of all places. Those bars are not constrained; their existence is not part of action. Something about the shiny arabesques in the piano, stretching themselves off into the treble skies, luminous C major, the texture of the piano writing at that moment, with the simple Alberti bass anchoring but not quite the disporting line above … Whatever it is! It is hovering, wavering, happily in C major but also conscious of being a hovering thing, not stable in and of itself.

It is not stable; it lowers itself to B in the bass, but still kind of hovers and wavers before “will.” 2 more bars pass. We are still playing, more darkly.

And only then, at that chosen moment, a sequence emerges—slowly, gradually—in the bass. A sequence of motions up by fourths; hidden “decisions.” This is (you realize) the most beautiful thing that can happen to this sound world … it clicks into place, it’s an epiphanic function. It arrives not imposed, but still from behind, from some deeper, tremendous necessity: a sequence which is the will. This will, emerging, slow to take effect out of purer sound, proceeds in large ascending circles rather than in a straight line, circles which grow larger and larger, more and more effusive …

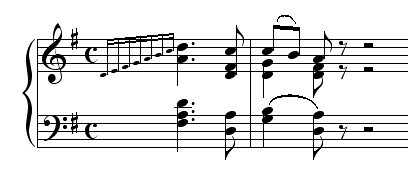

These growing circles of action lead us here, to this leaping idea:

… and again and again. This idea, the true closing theme, a kind of motto of ending/notending, is the joyful, thrilling wall against which the preceding will crashes. Is it the desired treat? Have we gotten what we wanted?

As in other passages, it seems the note (A) is a semi-free agent. Beethoven is sending the A up an octave to see what will happen; it’s a happy Sisyphus; it keeps falling down, and climbs back up again. Does it fall because it wants to leap up, or does it leap because it wants to fall?

For the answer/non-answer to this question, we need merely glance at the ending of the piano’s very first phrase. (The sudden scale up the octave, the first whim of the piece, the four-note relinquishing reply.)

Children are encouraged to play, not solely to win, but in order to play the game; this enlightened state of play rarely exists. The desire to win is wound into the game’s fabric. People also win competitions playing Beethoven’s 4th Concerto. But if the purpose of winning is play, losing is but the side-effect, a symptom of winning. Play at this level, at Beethoven’s level on the musical page, has no hint of triviality (it scorns even the negative connotation of “trivial”) though it is humorous, though it wavers and waffles; it is profoundly indecisive, it shivers with delight at the time you need and crave before you seek what you desire, it laughs with you at your losses and gains. And each time you move decisively forward, it reverses the field, so that you must play back in the opposite direction, so that playtime needn’t ever end.

11 Comments

“Tonic, the orchestra says”…. “B major”, blah blah

Sorry, I don’t know what that means; that requires music theory, which I recently threw away.

Children are encouraged to play, not solely to win, but in order to play the game; this enlightened state of play rarely exists. The desire to win is wound into the game’s fabric. People also win competitions playing Beethoven’s 4th Concerto. But if the purpose of winning is play, losing is but the side-effect, a symptom of winning. Play at this level, at Beethoven’s level on the musical page, has no hint of triviality (it scorns even the negative connotation of “trivial”) though it is humorous, though it wavers and waffles; it is profoundly indecisive, it shivers with delight at the time you need and crave before you seek what you desire, it laughs with you at your losses and gains. And each time you move decisively forward, it reverses the field, so that you must play back in the opposite direction, so that playtime needn’t ever end.

It is simply not possible for me to view any discussion of musical analysis through the lens of a football match, a game whose beauty I can certainly appreciate, but that has been called by those at the highest level, “war, without the guns”.

Did you know that in NYC the Rice Crispy Treats are spelled “Rice Chrispy?” There are two theories to this change:

1) To stay clear of branding rights.

2) They are very Holy treats.

Perhaps this is why you wanted one so badly…you’re really seeking Jesus.

I on the otherhand was not seeking rice cripsy treats, nor JC, nor seeing you on a train, but in fact I did.

And that was a wonderful thing.

This is like a music theory version of Einstein’s Dreams – which is awesome.

I even like the football reference…

Dang! When I studied this piece, its personality perennially confused me. I adored every morsel of it, but confess that I never really ‘got it.’ Could have used a few Jeremian analogies for sure, back then…my coach was ‘above all of that.’

THAT SAID, the analysis was a bit of a disappointment for the sole reason that the Rice Krispy Treat Situations alone had provoked such gut-wrenching, ball-busting laughter from this erstwhile placid abode that the neighbors all called 911…

I missed a step in this recipe and my Aldwell Schachter is now all sticky. I’m denking it in coffee.

Metaphor, krisp and Schenker… I like the little double chocolate cookies myself. You’re on the Starbucks marketing payroll, yes?

Situation 3: ah infancy. I picture a UWS toddler unsure whether life is awful or rad (who really ever knows on the UWS?) alternately screaming and noshing through tears on the krispy treat his expensively highlit mother has shoved at him.

True story.

hhmmmm … i have a proposal … i think your blog entry would translate wonderfully to film. i make videos on youtube, and i would love to turn this into a short video, focusing on the three rice krispy treat situations and delving a bit into the music. can i have your permission to do this, and use your words. please reply to this comment or drop me a line at claire.karoly@gmail.com. thanks!

I think one situation that strikes me as a possible “Situation 2” would be in the context of a particularly sublime variation in a Theme & Variations. I mean in the sense that the variations themselves set out a series of treats, and you don’t really know what you are in the mood for but you kind of wander into the piece looking for something tasty. When one particular variation provides that sudden moment of transformation where it feels like this has been what the theme has been waiting its whole life to do, that’s your Type 2 Treat. In the case of Mozart (since you want some Mozart) they often seem to be the codas. Think of the very ending of the Clarinet Quintet, for instance.

And speaking of codas, I was also pondering what sort of Krispy Treat you have when there are multiple sublime moments that sort of pile up. For example, the end of Schumann’s Davidsbundler Dances. We get the “as from a distance” moment of mysterious waiting (already some sort of treat), followed by the return of a particularly nice theme from earlier in the piece (which feels like a genuine Krispy Treat except…) followed by that last little waltz that manages to be simultaneously happy and sad (and is a different sort of treat, but just as remarkable) Maybe that last movement is a nice glass of milk or cup of coffee or something that washes down the previous treat. I dunno.

I very much like the little audio player thingies that you are putting in. They are particularly nice for those of us who are musically inclined but – through no fault of our own, though probably through a lack of vision from our parents – musically illiterate. But you seem to give up half way through (an evaporation of will?), which leaves us hanging. Are you going to continue to do this (put them in, not leave them out)? I suppose it’s too much to hope that you revisit some earlier posts with the same gadget. If you do I promise to re-read them.

Sorry, me again. I have been thinking about your three part analogy and I think there may be a crack or two in it. It comes down to point of view, or rather for whom the analogy holds true. In situation 1, you are assuming the role of Wagner; he who intends to write a musical description of, well, you know… In situation 3, you are the listener, pleasantly surprised by the Heisenbergian materialization of the horns – improbable but not impossible. We cannot know, but it’s reasonable to assume that Beethoven was not surprised in quite the same way. Given the expression on his face, in bust and portrait, one might even suppose that he was given to thinking very hard about what he was doing. Situation 2 might neatly be ascribed to you playing the role of yourself, the performer, exercising your spontaneity muscle across the spectrum of allowable improvisation, or interpretation if you like. All of which makes it a very good analogy but for something other than what you might have intended. Since I am neither the owner not the former owner of now-shredded works on musical theory, I have no reason to hold this against you…

You’ve left our the best moment of all, like the bridge (?) section of the slow movement of the Hammerklavier.

You think you’re about to bite down on a Rice Krispy and suddenly you are overwhelmed by the most incredible flavour sensation, a 1973 Chateau d’Yquem, perhaps, and you just want to weep.