One could have paid a lot of money over the last week to see grown adults act like children. There was Dawn Upshaw , daring to prance around the august stage of Carnegie Hall on an imagined hobby-horse. And there was Richard Goode, tenderly coloring Mussorgsky’s quirky chords around and behind her, making tritones sound like a child’s wrinkled nose.

I find this Mussorgsky set — “The Nursery” — an unbelievable masterpiece: brilliantly funny, perceptive, so exactly mirroring a child’s behavior, in all its innocence and inconsistency … and quite sad. The child is visited by little tragedies (crashing on his hobby horse, for instance, getting a little “boo-boo”) and in these melodramas, these minor losses-of-innocence, I feel the adult’s premature, imposed regret: the implication that the child’s miniature sadnesses are precursors of (rehearsals for) greater, later ones.

But then, Mitsuko Uchida and Mark Steinberg played the E minor Sonata of Mozart (among others) on Saturday night. The first movement is the adult tragedy that Mussorgsky foresees: stormy, brainy, beset. And so, too, the beginning of second movement, a melancholic, minor-key menuet. But finally:

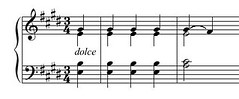

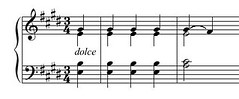

She played with the wonder of a child. We have not really heard E major before in this piece; for me it was more like I had never heard E major before, ever. And certainly nothing like the seventh chord which the E major leads to… She played the beautiful, rising response:

And then there is the longer phrase, with the motion temporarily moving to the left hand, the phrase that connects, the longer arc that “justifies” the two preceding fragments:

In the Mussorgsky, a child’s innocent pleasures are somehow colored, spoiled by adult awareness. (What could the child possibly be nostalgic for? his former life? Really, only adults are nostalgic …) Time and events encroach. But here, in Mozart, the (extraordinary) adult’s music is rebuked, refuted by this (even more extraordinary) bubble of E major, this frozen wisdom of a child. Nothing encroaches on it; time is, as they say, suspended; it is not threatened by possible decay; it is immortal, pure, rounded.

Mitsuko taught me many things in her playing of this section… In the longer phrase (3rd example, above) I had always looked for beauty on “the way up,” on the leap from E up to C-sharp. But the most beautiful moment (the defining moment) of her version was, subtly, one measure later, on the way down. (The two arrows show the two places.) I had always deceived myself, or let Mozart deceive me. The phrase appears to be about rising, towards something; but it actually turns out to be about relinquishing. After all, we have heard that C-sharp already, in the second “phraselet;” it is letting go of the C-sharp that has yet to be accomplished.

I always found this place intimidating to play. If a musical moment is so concentrated, so distilled, you want it to last forever, or at least longer than “real time.” It is easy to get in a Catch-22: no matter how much you stretch it out, it never seems long enough; and if you stretch it too much, it gradually falls apart, like dough. It is of course written in the “language of time;” without a certain timeliness, without its rhythm, it would become meaningless, and yet, and yet… it seems to grab at time, attach its hooks to it, not want to let go. So as a performer I feel torn between two selves, the person who must keep playing the quarter notes, feel the pickups, the meter; and someone else who just wants to listen, to savor, to enjoy … between an adult and a child?

EVEN BEFORE MY COFFEE yesterday morning, the very first thing I did (usually I start counting events of any day from the moment of my first sip of coffee… not A.D. but A.C. … nothing “really happens” before coffee) was go to the piano in my pajamas and try to play these phrases, try to absorb what Mitsuko had shown me about them. This means it was an emergency for me. After a couple tries, I won’t say it was the same, but it was “good enough.” I did not feel hurried, or distended; I could savor the beautiful chords (as sonorities in their own right) and still keep things moving and meaningful. I was happy and I made coffee with a serene self-satisfaction. I stole this happiness from Mitsuko, or borrowed it…

One more thing Mitsuko and Mark did to cement and circumscribe the beauty of this section… There is a pause in its second half; they waited out this pause, the last time; they both breathed a long breath. It was longer than it “should have been,” but they entered together, without anxiety… So that there was this effect of infinite patience, combined with anticipation… for the last time we will hear the theme, for the final, rounding E major strain. That way, I could hear it, one last time, fully appreciate it, and let go. I’m not sure I’ve let go of my childhood with the same equanimity.