It is incredibly difficult to step from the sacred to the sensual, or vice versa, convincingly. Many composers have stumbled there, at the perceived threshold of transcendence. You might argue the journey sacred-sensual (round-trip super-saver fare) was the project of much of the later 19th century, a project which mostly failed. The most colossal, brilliant failure to cross this divide was Liszt’s. Oh he felt it alright, the need to merge sensual and sacred, perhaps more than anyone. He was, in “real” life, the poster-child of this paradox. But then, it seems, he couldn’t be objective enough about it to paint it for the rest of us. His failures are almost always of tone, a failure to be able to be taken seriously at his most passionate: a incapacity to see beyond himself to imagine the rejuvenating, remorseless, creative cynicism of the human mind, which tolerates only so much bombast before destroying it with rolled eyes.

His sacred moments are either strangely sensual or annoyingly self-righteous; his sensual moments often disintegrate into hedonistic wandering (much like my life?) …

I’m sure someone will argue with this, but for me the name Beethoven and the word “sensual” don’t mesh. Beethoven is almost never languorous, for instance (but always rigorous.) Sometimes, in some very special slow movements, he approaches this world (“Emperor,” “Archduke”) but never releases us entirely into it; he cradles us but never fondles us. HIs strength, or yours, is always at stake. There are, to be sure, amazing sensory pleasures, rivers of beauty, but never do you feel you can fall asleep in them, let yourself dissolve into the desired impossibility of sense without mind. Whereas, to take an opposed instance, Rachmaninoff is the master of afterglow, if nothing else; many of his greatest moments seem like coiling smoke rings from post-coital cigarettes; he should be sued along with the tobacco companies.

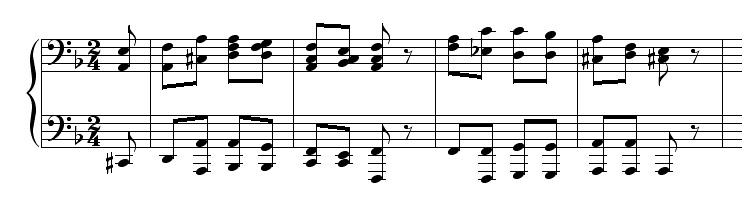

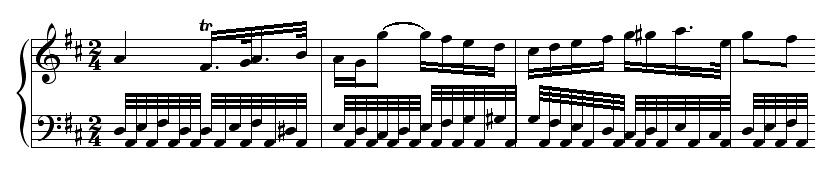

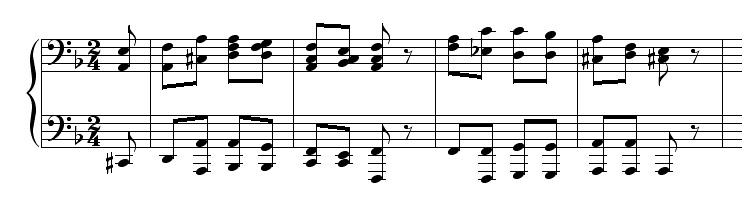

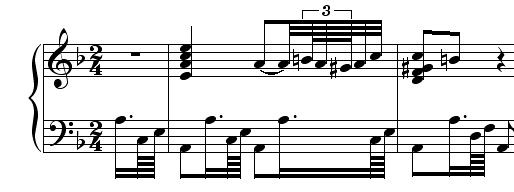

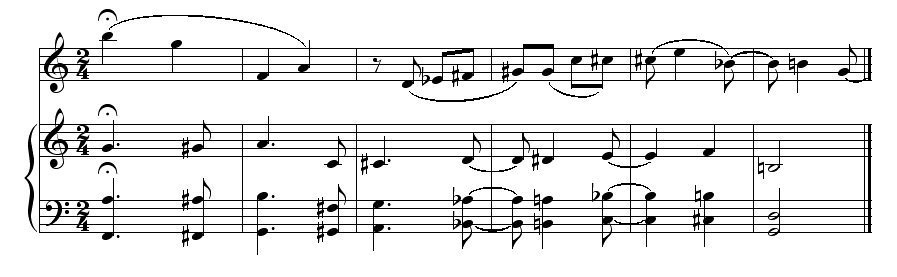

When Beethoven is after the spiritual (last movement of 109, 111, slow movement of 102 #2, etc.), he usually employs the hymnic. It is a sensible matching of genre and aspiration. The hymn, the prayer: it is serious business. There is something measured about this, something particular, discrete, note-by-note, reasoned; and it is only against these columns of severity that any kind of sensual decoration finds play. The slow movement of 102 #2 (to take one of many instances) begins with a funereal hymn, where the phrases are as rhythmically predictable as the lines of a limerick:

These become sombre dotted rhythms, the more majestic trappings of a march (distancing, observing, genre as obstacle):

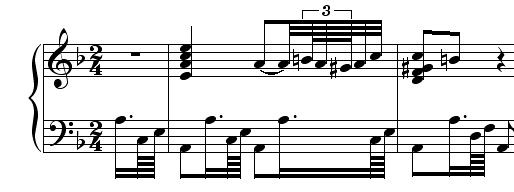

Now out of these austerities, these deliberate restrictions, comes a heavenly middle section, when minor gives birth to major, and the rhythms find flow …

Here is the spiritual center, the beautiful core, molten major-key lava at the middle of our funereal world. If there is something “sensual” in this movement, it is here: the sensualization is partly the release of the rhythm, a breeze drifting through our window of time, but if you are looking at the pitches possibly one of the most sensual moments is simply the switch from B-flat to B-natural, the pianist’s little neighbor motion which opens up a whole new world (or an agonizingly beautiful memory)…

This is a classic instance… this gesture, and just this, is seemingly enough sensuality for Beethoven (just the glimpse, the touch); as the major section unfolds, the most breathtaking moments in fact are simply ascending scales, arpeggios, things that seem like girders, structures, things that cannot weaken.

For the Romantics this was not enough. (Why?) There is something about humanity’s sensuality and sexuality that must be an integral part of their musical world. (It is true, this is mostly missing from Beethoven, or has been redirected, sublimated.) Why should it be missing? And once it is included, what are the consequences? There is the danger that the sensual becomes cheap, becomes sickening, becomes its own destruction. Sensing this, insecure about their own beauties, nervous about the morality of sounds, the composers of the 19th century seem so often to try to find “purpose” for their sensualities, “reasons” to be beautiful. And so the uneasy fusion of profundity and pleasure.

Many of the world’s favorite moments in Wagner are exactly this: triumphant, shocking fusions of sacred and sensual: Isolde’s Liebestod, obviously; and the paternal, idealized love of Act III of Die Walküre, with the fire as sensual symbol, as caging freedom; so, too, the unbelievable, unleashed passion of Siegmund and Sieglinde in Act I. Yes, they are sexually frenzied, out of control; but they are also part gods; their sexuality is fated, divinely sanctioned, desired, united with spring, season, rebirth (and also with destruction, taboo, tragedy)… the first cello choir passage where Siegmund and Sieglinde gaze at each other is one of the iconic passages of Romanticism, and of chromaticism. It is frankly erotic but at the same time pure, beautiful, perfect.

As Roland Barthes puts it:

Besides intercourse … there is that other embrace, which is a motionless cradling: we are enchanted, bewitched: we are in the realm of sleep, without sleeping; we are within the voluptuous infantilism of sleepiness: this is the moment for telling stories, the moment of the voice which takes me, siderates me, this is the return of the mother … In this companionable incest, everything is suspended: time, law, prohibition: nothing is exhausted, nothing is wanted: all desires are abolished, for they seem definitively fulfilled.

Yet, within this infantile embrace, the genital unfailingly appears; it cuts off the diffuse sensuality of the incestuous embrace; the logic of desire begins to function, the will-to-possess returns, the adult is superimposed upon the child. I am then two subjects at once … through all the meandering of my amorous history, I shall persist in wanting to rediscover, to renew the contradiction—the contraction—of the two embraces.

The contraction of the two embraces!

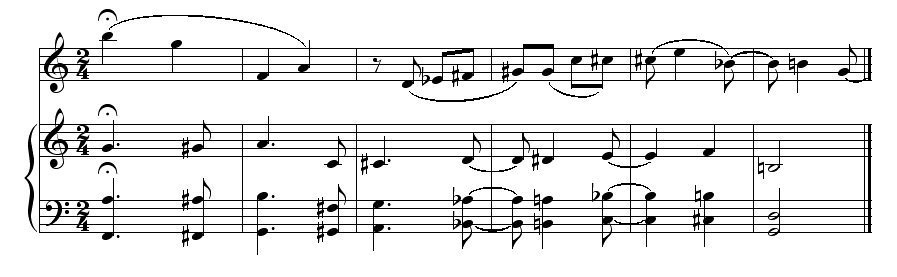

I have been practicing the Berg Chamber Concerto, for performances in Philadelphia, and as happens every time I approach that piece, I find myself playing over and over again the part where I don’t play: the beginning of the slow movement. (I am not always a model of efficiency.) I look at the page lovingly while I slobber my cereal. I call my friends on the phone and say “listen to this” while tears form in my eyes and then I suddenly have to hang up, saying I have to go. I try to share the unsharable. I wonder, idly, if I could ever somehow convince my parents to listen to the piece attentively up to that point, as I feel sure they would be happy once they got there, and maybe then we would all understand each other a bit better.

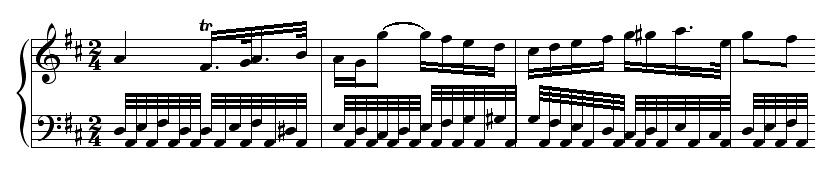

Berg makes the violin into an apparition, the beauty of being. Just as Mozart makes the first appearance of the clarinet in the “Kegelstatt” into a meditation on breath, on long-breathedness, this appearance of the bowed string after all the blown winds and struck keys of the first movement is a sensual “happening” first and foremost: a sound made new. The drawn string, the weight of the bow …

What comes just before the violin is an escalating waltz, toppling itself in lustful whirl. The theme of the first movement seems, in its searchings, to “want” to be a waltz (itself a fraught symbol of want) and always culminates in a beautiful, relinquishing coalescence: languor, emerging from abandoned surges and urges. The last variation allows this languor to grow and evolve; the waltz turns crazed, demonic, canonic, gets fruitful and multiplies: the piano emphasizes the accompaniment (vulgar, obsessive) and the curling melodic idea curls and turns ever more, and in the final measures of the first movement the bass ascends chromatically, wildly … into …

One of the truly heartbreaking things about this passage is so simple: the fact that the bass continues climbing. Even though we have crossed an abyss of dynamic, of thought, of sound, of meaning, even though everything has changed, though a thunderbolt has struck the piece’s world, this one continuity, this one argument remains. It is like an aftershock, some sort of drifting, remembered tendency which cannot, should not, be abandoned. The upwards chromatic: chromaticism is closeness, intimacy… the smallest possible interval, the overlap and brushing of bodies … there is no gap between the skin of one note and the skin of the next.

You might say: this page of the violin’s entrance is terribly lush, Romantic-with-a-capital-R. (The R-word can be disparaging.) The passage is thick with sounds that could so easily be clichés: 7th and 9th chords, jazzish mixtures, a quivering A-flat major tremolo chord in the winds … And yet, though built with decadent, sensual materials, the girders of late Romantic excess, this passage seems to me absolutely, strangely, wonderfully holy: you wouldn’t want to alter a single note, the notes seem suspended in a kind of ideal space: it’s like a chromatic hymn, a hymn in a silken bed, lusting for nothing but to be. There is some connection, for me, between Beethoven’s hymnic style and this passage, some shared reverence and wonder, some separation from the world’s ongoing narrative. (In the Beethoven, inevitable death; in the Berg, inevitable desire.) I am completely spellbound by it; for those minutes, if I want to live another moment, it is because I want to hear what chord comes next.

Berg achieves what so many Romantics could not: the contraction of the embraces. The sexual is in there with the sacred, and they are not uneasy bedmates. He hits that magical sweet spot, straddles the divide, which is partly just a form of faith: faith in the touchable, the tangible, the paradoxical perfection of the flesh. The body is not a curse, a collapsing corruption. Look, he says, it yearns, I yearn, you yearn (ever upward, chromatically), and though the yearning is endless it is not empty.

And why is it I am so touched by this? The rest of us—for whom perhaps the sensual and the sacred are not one indivisible territory—glance at them separately, from the vantage point of our peak of selfness, from our dilemma’s horn; we wish we could travel to them both at the same time. But they recede to opposite horizons. We must buy two tickets, or stay at home, and dream.