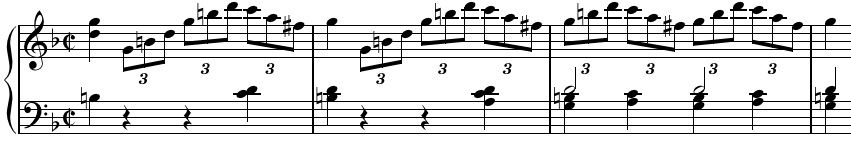

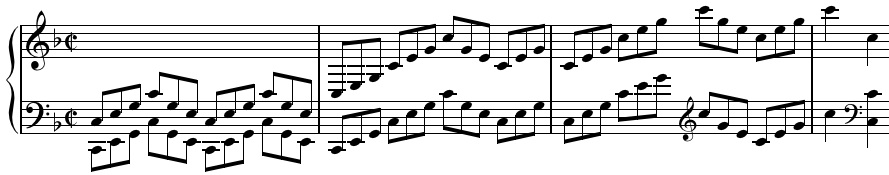

Without introduction, Mozart’s K. 533 leaps into being:

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… and one of the many things one could love about this idea is that it says thanks but no thanks, I don’t really need or want to be harmonized.

It is self-sufficient. As evidence of its smiling sufficiency, notice: the second half of the idea is (merely?) the same as the first, bouncing off it, like a ball off a wall. This idea is full of flavor, but devoid of fat. Its richness is made not of depth or weight but of mutability and lightness. A compendium of leaps, let’s call it a Puck of notes: agile, clever, laughing off consequences.

When Harmony makes an appearance, he’s dreadfully dull:

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

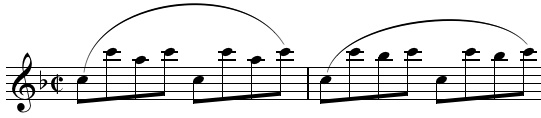

… not Puckish, to say the least. In place of the melody’s agility, we get a one-note wonder: F, F, F, do do do. Meanwhile Melody runs up and down the F-major scale …

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… pausing at the bottom for a cheeky F# neighbor, curving round the top for a delicious G escape tone–ornaments of wit and pleasure. Which begs the question: why is the Melody partying down while the Harmony is stuck at home? Why is Mozart making Harmony the butt of Melody’s jokes?

Mozart is proposing an ideal of Melody: playful, wayward motion for its own sake, unhindered by harmonic weight. Often it is hard to answer the question what is music about? but sometimes it seems beautifully simple: this first movement of 533 is at least partly “about” this Ideal of Melody. It is about this “glee of the solo,” and its ramifications: its curious interactions with the world of harmony, like a child testing the limits of its crib.

In this fantastic movement, this mischievous war of Harmony vs. Melody is an obsession, a game Mozart cannot stop playing. For instance, some ways along, a good and proper cadence appears:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

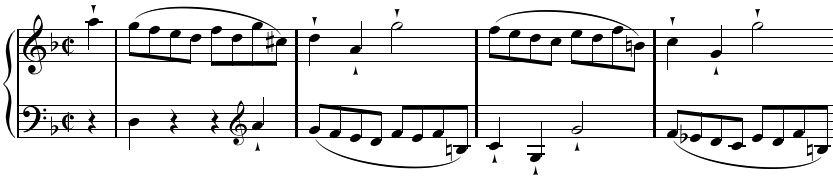

Now, if you know something about Sonatas, you know that this sort of moment is Something Required, a kind of rest stop on the freeway of the Classical Work. Even if you don’t know anything about Sonatas, you’d feel the need, the reasonable and necessary urge in the middle of the journey to fill up on musical gas, and clarify your destination: i.e. we’re here, kids, C major is served! But this necessary Harmonic Declaration gets the most delightfully unnecessary Melodic Rebuke:

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… yet another gleeful solo, a very improper little tune, yearning for a whimsical rapscallion of a bassoonist to play it. From the cadence (rest stop) to this (unscheduled diversion), a crash of opposites: the solo’s a renegade who wanders off the clearly mapped spot out into terra incognita.

I can’t resist savoring this Puckish solo one bit at a time.

Stage One. It does something quite reasonable and inevitable, i.e. resolves to C:

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The Catch: This resolution comes too soon, and with only one note, instead of the whole chord! This resolution (though natural) is also odd, asymmetrical: an off-kilter truth.

Stage Two. If we can resolve with four notes to C, why not continue on to A, by logical extension? …

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The Catch: Resolving to A requires G#, a strange bump in the road of C major. This G# is the joke-within-the-joke, say, the banana peel on the stairs in the Tom and Jerry cartoon.

Stage Three. As if slipping or skidding on this G#, Mozart throws in a little pirouette …

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The Catch: Who knows where this pirouette will land? The complications of this passage are snowballing.

Stage Four. Clarification. Four notes make perfect sense of it all:

![]()

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The Catch: Actually, all of this wandering about has led us right back where we started: to G.

In other words, this whole rascally episode was unnecessary? Irrelevant? A diversionary tactic? A naughty parenthesis? Marvelous, Mozart; bring it on. If this gleeful solo wrote a self-help book, it would remind us that it’s great to have goals, but–c’mon dude!–don’t forget to smell the roses. You can tell Mozart has a tremendous, almost over-indulgent affection for this idea, especially the little “banana peel” G# … in the recap, he really lives it up, throwing endless slippery accidentals under our listening ears, merging this rapscallion with the main idea, which is a kind of farcical tour de force.

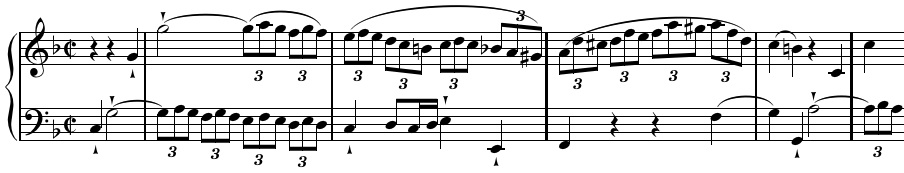

So this movement is partly about the Glee of the Solo. But its other main “subject” (or topic, or obsession) is even simpler, in fact it’s merely a statement of the patently obvious: let’s call it The Pianist Has Two Hands.

The recurring trick of this sonata–and it’s a joke of a trick really–is to take whatever happened in the left hand and put it in the right, or vice versa. If you notice that despite the melody’s agile maneuverings the first eight bars never manage to leave the tonic (look it up, non music theory people: it’s the home key!), you might feel there’s a glimmering smile at the end of the eight bars, when the phrase stops for a moment, a hint of slapstick, such as: well, that didn’t get anywhere, what do we do now? The slightly awkward pause … is that the punch line? … yes, maybe, but also it’s the first iteration of a joke that is unfolding. Mozart’s solution to the pause is simply to start again, with the same melody in the left hand:

![]()

… which is a non-solution, almost a desperate maneuver. But Mozart doesn’t DO desperate maneuvers; he merely enlists them in his schemes. Maybe you might hear in this a child’s game, tried and true adult-irritator, of repeating whatever was just said to them? An interesting consequence of this “hand exchange” is that the Alberti Bass, which of course by some definition of definition “should” be in the bass, ends up in the right hand, sounding a bit weird, as if it were in drag: an Alberti Treble.

Now this sounds like one of those nerdy things, deserving the yawniest of yawns, oh yes how exciting an Alberti treble, but don’t you see!!!, when Mozart submits the essentially homophonic texture of melody and accompaniment, the very bread and butter of the clear, simple Classical style, to a Bachian voice exchange, he’s committing a kind of musical pun? He’s letting a Sonata morph into a Two-Part Invention and Invention into Sonata; he’s letting the intellectualism of counterpoint have a little outing on the fields of homophony, letting the two styles make fun of each other. Agh, how can I put this so it sounds less abstruse? If you think of the initial idea as Puck, there is something wonderful and perverse and funny about making Puck do counterpoint: it is a bit like making Tom Sawyer whitewash the fence. (Of course he will trick his friends into doing it for him.)

Now, the pacing of this contrapuntal ping pong constantly changes, and thus the “idiotic” game becomes interesting; the ever-increasing sophistication of the treatment vies with the simplicity of the premise:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Wonderful imitations. But this is just the beginning, later on the interruptions and restarts are incredible:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

But, of course, marvelously and wildly, at the end, all counterpoint is swept away in a unison:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… take that, counterpoint! Both hands are now united, but they end on the off-beat, with a vector heading off into the treble, a brimming, surging cadence.

So, Two Topics, two subjects to this movement: one the Glee of the Solo, with all its associations of lightness and mockery of harmonic “profundity;” and the other the continuous Exchange Between the Hands, which begins simply but evolves into a highly sophisticated game of Bachian counterpoint.

But these Two Topics–though appearing to contradict each other–are not separate. The theme itself is bouncy, particularly its lovable leap of the octave. Then–here’s the trick–this bouncy theme begins to bounce back and forth between the hands. The bounciness of the melody, by Mozartean logic, becomes a bounciness of counterpoint, an irrepressible desire to play back and forth … the two main topics of the movement are linked by metaphor, by a contagion of meaning. And this enchaining of meaning, this ping-pong playful conversion of the idea, is maybe the Third Underlying Topic of the Sonata, who knows?

One thing I forgot to say … One thing I admire about the beginning of this Sonata is how it is a rebuke to all stuffy, pompous beginnings, all ominous beginnings, all dense, fraught whatever. Its charm is disarming, natural, irresistible. It has no seriousness. And yet, as it unfolds, this movement has more brilliance of mind stuffed into it than you could possibly imagine; it draws you into an incredible seriousness of play. Between the seriousness of the inventiveness and the deceptive simplicity of the premises … Mozart is showing us two faces at once, kind of shimmering between them. It’s not the usual cliché, i.e., that Mozart’s great artfulness is disguised behind an effortless, childlike simplicity … blah blah blah. For some reason I’ve always been bored by that formulation, it seems so tailored for PBS documentaries. How about an alternative? Mozart’s iconic two-facedness: he’s standing on the boundary between learnedness and simplicity, wickedly making fun of the very distinction itself, as if to say “art isn’t about difficulty, or simplicity, you moron.”

The question of life being: how to have that much fun, in reality.

12 Comments

I just wanted to let you know that I decided to test my gifted pianist son with the first line of music in your blog entry. I copied it into word for him so as to not give any clues.

Even though he doesn’t have all that much experience with Mozart yet I thought it was worth a try. He is 14 and has only had about 3 years of lessons and plays at the advanced level. He entertains himself by hanging out at a university music library reading scores! He could tell that it was Mozart but didn’t know which piece it was. The child is a walking encyclopedia of classical piano information! If there was a “Name That Tune” of classical piano music he would score incredibly high! lol

As a whimsical rapscallion bassoonist myself, I have to say I enjoyed your description very much. I will now take a moment to mourn the fact that he didn’t get around to writing me more banana peels….

Melissa, I’ve noticed many bassoonists have a strong rapscallion gene. Thank goodness there is no cure for this.

Movable do, sir? I’m calling the solfege police.

Movable do is the only kind of do worth having.

If only my music analysis classes had had one tenth of the creativity and vitality of this, Jeremy, I may have stopped treating them as my weekly open-eyed-sleeping practice sessions…

Pure genius. Both Mozart and you.

I’m too lazy to do the necessary research with respect to chronology, but this Mozart sonata always reminded me of Haydn’s F-major sonata Hob. XVI/47, which appeared in the same year Mozart’s sonata was written but which (if I were to use my ever-fallible gut) looks as though it might have been written some 15-20 years earlier.

The Haydn sonata, too, has an opening in mock 2-part invention style (something for the younglings) which gradually morphs into something more “modern”, culminating in difficult (for me)runs in thirds and octaves.

Probably just a coincidence, but submitted for your consideration.

I am a real Jeremy Denk fan, having heard his Ives’ “Concord” and Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier” in Brevard, NC, where I maintain a blog about the creative and performing arts in Western North Carolina.

Throughout the last twenty years, I have always annotated my Mozart by identifying orchestration possibilities (such as JD’s bassoon) or sometimes operatic voices for individual voices in important moments. How gratifying to realize that JD does the same!

I’m an amateur studying this work. I very much agree with your analysis. However, I went searching online about this piece to try to learn something about the Andante which seems one of the weirder things Mozart ever did. He seems to have set himself some sort of problem to solve for himself and has little interest in whether his audience follows or is even there. “Can I turn off my amazing gift for melody and follow a very austere motive wherever it goes?” Reminds me of Beethoven in his “to hell with the audience” moods. I’d love to know your thoughts.

Hi,

I write about music myself and create my own sound examples, rather laboriously. Can you tell me what’s involved in creating the elegantly presented audio examples — and notated examples, for that matter — on your blog, or point me in the direction I need to go to learn.

Your blog is wonderful. Your playing even more so.

I read this a while back, but just have to say I love this one! Man, I missed your when you were in S.F! . Absolutely love the blog. More please!

😉

We enjoyed hearing JD’s Mozart in San Francisco two weeks ago with the SFSO. He has definitely come a long way since playing piano prodigiously for Sunday morning services at the UU church in Las Cruces, NM!

His self-composed cadenzas for the “Elvira Madigan” concerto were every bit as stunning as Glenn Gould’s outrageously Reger-esque cadenza for Beethoven’s 1st concerto was in the late 1950s. Onward, chromatically!