I was at the grocery store and became aware of the tremendous availability of yogurt. The cavernous case of dairy glowed and grinned: slurp me! It is, for many New Yorkers, an exotic thrill to wheel a cart around the fat aisles of the heartland. I was in Bloomington, Indiana, for a couple days, revisiting a juicy slice of my past, and went to the store despite no desire for foodstuffs. Perhaps I had a desire for something! … but then as I wandered I lost it, in a Hoosier daze. The end result being, I took a tour of the whole place, the infamous, eternal Kroger’s, in the same way you might circumnavigate, say, the Louvre; one wheel of my cart stoically failed to operate and my vessel kept drifting ever leftwards, towards pyramids of baked beans, towards remaindered Easter candy, towards the saddest, most prosaic grocery items imaginable. Hard to starboard, captain; ahoy, gherkins!

Yogurt comes in flavors, and classical music should come in flavors too. I suppose it does: Russian virtuosos, for instance.

Composers are flavors and performers are flavors and so a performance of a specific composer is a flavor of a flavor. The superimposition of flavor. Sometimes the oppression of a flavor: as if limes suddenly decided to show bananas who’s boss. And so you read all sorts of reviews and blogs which say “harpsichordist Joeschmoe’s honey glaze overwhelmed the juniper berry of the music” or “the humble well-considered servility of Doofus’ hollandaise allowed the currant undertones of the music to emerge in all their complexity” and so forth.

“I’ll buy all your yogurt for today,” I said to the woman next to me, who was piling plastic containers into her cart headlong, “if you’ll come to my free concert tonight of Beethoven and Ives.” She moved on.

I tried a different tactic with the next yogurt acquirer. “I’ll dump this yogurt all over your head if you don’t come to my free concert tonight of Beethoven and Ives.”

While the manager spoke to me in (perhaps unnecessarily!) strident tones, I couldn’t help going over in my mind all the interesting, fruity flavor combinations of yogurt and what flavor am I? Youngish American Pianist (Also Blogger!) flavor? That is certainly a mouthful. Oh, my flavor! On whose tongue should I be melting right now? Oh, Gods, find me a flavor, find me my perfect flavor and pasteurize me and lab-test my Nutrition Facts and slap some protective tinfoil on me and sell me in grocery stores all around the land!!!

So my mind soared.

Back in the car, I trembled in fear of flavorlessness. It occurred to me that all of classical music, to many people, is one single undifferentiated flavor, and not a great flavor at that, something that you might obtain at Luby’s Cafeteria, like stewed prunes, but without the pragmatic associations of the benevolent laxative.

This parking lot has always interested me. It has a general downward veer, so that the Kroger appears to be a City shining upon a Hill. Because of this slope, it has a little metaphysical story to tell, and retell. If you sit and watch for a while, out of the corner of your eye something in the matrix will move, a surreptitious metal basket; the urge is cautious, then lograrithmically lets loose; it meets destiny in a car door or a curb or some poor person runs after it, trying to save it from itself. The eventual freedom of the cart, racing and rattling over the pavement towards the liquor store, is fantastic. You cheer it on. Whose paint job will you ruin this time on your path to self-realization, you crazy cart?

Headline: Deranged Classical Pianist Found In Indiana Parking Lot Watching Shopping Carts.

“He was supposed to be playing the Concord Sonata, officer, but we found him here, staring out the window, rocking back and forth …”

It would be ridiculous to have feelings about the Kroger. It’s a warehouse of food exchange, an empty case of trade designed to be as similar to others as possible, designed to conform and vanish. Much of the food inside is also empty of content, pure nutritional parenthesis. And yet I cannot deny the intense reality of my feelings about the Kroger; they are clinging to it like a barge in the ocean of experience. There was one night where a bunch of us got the terrible munchies (without chemical stimulants, thank you) and at the same time began to meditate on the joys of Captain Crunch cereal, and we ran out to the Kroger and got every imaginable flavor of Captain Crunch (with and w/o their eponymous berries) and a spectacular array of milk and I still can remember pulling the lids off the milk gallons and the sound of the milk hitting the cereal and the terrible ache of the roof of my mouth the next morning and the laughter of the group, all my friends of that time and all our complicated unexpressed whatever, sexual tensions and mutual admirations and the usual stews of love and resentment and the feeling of having your life invaded which was what you wished for, right … right? When I sit in the parking lot of the Kroger, watching carts drift downhill, I simply cannot help bringing this moment to my mind. Can these feelings really sit atop something as empty as the Kroger? As soluble as Captain Crunch?

Though our lives, through the machinations of real estate developers, etc. etc. are being lived out in ever more predictable grids, in the sway of generic chains whose profitability is pre-calculated, we insist on living our lives specifically. Never mind that all our of most tender conversations are happening in a Starbucks which looks exactly like every other goddamned Starbucks in the world! Nonetheless, you must face it: this is where your tender conversations take place, you must define your difference amongst this monotony.

Now, imagine you are Charles Ives, and you are listening to hymns and ballads since a young age, and at some point it must occur to you that a lot of these hymns and ballads sound the same. That they drift into each other. That they draw upon a certain well of ideas and if you are not careful you could slip from one to the other with little difficulty. Interchangeability is a characteristic of the hymn structure and the parts are supposed in some ways to conform to a generic ur-idea, so that the parishioners are not reinventing the wheel every time they sing a hymn.

Well, I was explaining to some doctoral students at Indiana University in my surely annoying way that 1) there is this crucial five-note descending idea in the “Concord” Sonata, and that 2) Ives’ formal procedures could be perhaps described as hints followed by explosions, or glimmers followed by apotheoses … That is, you don’t get something at all once, but you have faint intuitions, and then at some point (according to some mysterious, wayward law) the intuitions gather enough steam and suddenly you GET IT. This epiphanies are incredible, staggering, often also staggered, so as to arrive when you least expect them.

Even Beethoven doesn’t aim this far into the subconscious; he likes to present his ideas fairly whole at the outset, so their later manifestations can seem logical outpourings. Ives is interested in what we might call now a more “realistic” portrait of understanding, as opposed to an idealized one.

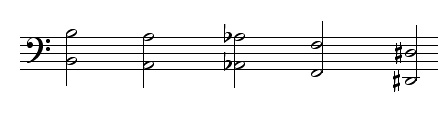

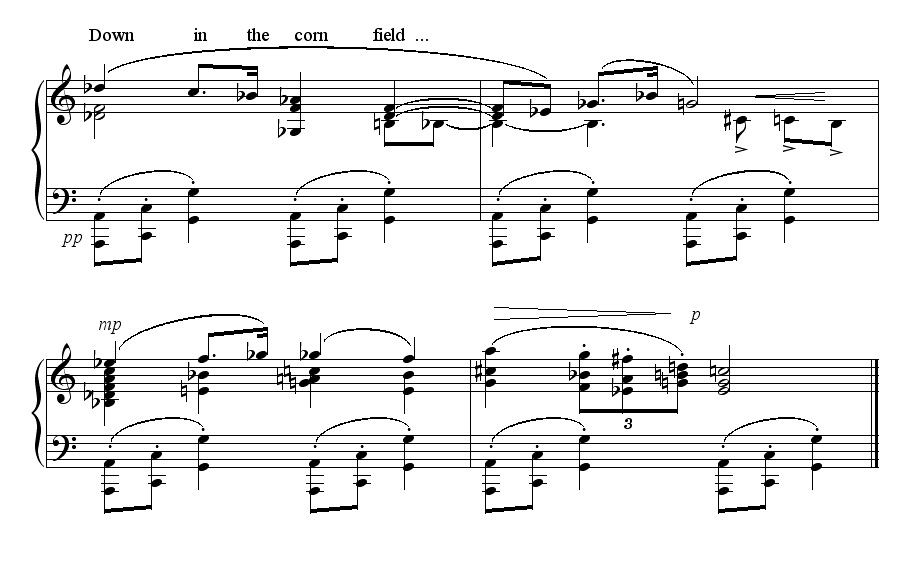

So the first hint of this five note idea comes at the beginning of the “Concord” in the left hand:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

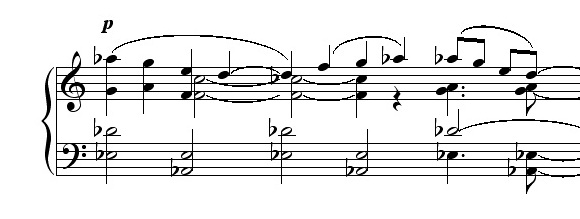

And another hint comes here:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

And you might say: hold on a moment, Denk! These don’t resemble each other really, since the intervals are somewhat different, and the first one has five notes whereas this second version is just four notes, etc. etc! But this is precisely the point. Ives is not that interested in absolute, exact, mathematical equality (12 tone, set theory, etc. etc.) but in the the space where the specific identity of something blurs into the general, generic place where it might eventually have no identity at all. The place of perceived, but doubted, resemblance.

As it turns out, this idea (vaguely perceived or not) reaches a kind of apotheosis, midway or so into Emerson:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

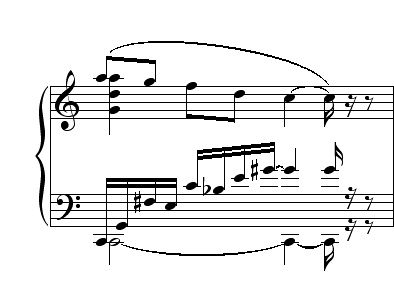

But you ain’t seen nothin’ yet. Because in “Thoreau,” Ives revisits this idea

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… ah, a beautiful woodland version … one for Walden Pond … and yet there is one more, even more powerful …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

And you realize: it’s “Massa’s in de Cold, Cold Ground” by Stephen Foster (particularly its refrain, with the words “down in the cornfield …”) It’s a turning point, a defining moment in the piece. If you didn’t get the Foster reference, Ives brings it up in his note; he wants you to know. Now, “down in the cornfield” is not something I care about right now, in my life. How about you? But I must say I played it through for the doctoral students, as an academic responsible person, showing them the source materials, etc. etc. …

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

… and had a flash of feeling about it, some sort of leftover Americana sentimentality. I felt a real feeling for a song which was utterly unreal to me, which was merely or mainly an image.

For much of the “Concord” Sonata, the five-note idea floats around in a sphere of generality, in a sphere where it could be anything. But Ives then affixes it. He compromises its free float, by attaching it to the Foster tune (and onto the tune’s whole complex of associations …)

On the one hand, you have five notes that could belong to any number of tunes, that seem in some way a kind of armature of the Hymn with a capital H: a kind of ur-Hymn-fragment, a shifting bit of hymnic DNA. And on the other hand we have a very specific referent … a composer, a flavor, a text, a sentiment. The general idea has suddenly been flavored, or identified, shot through with specific self. But have we lost something by abandoning the general for the specific, have we limited ourselves? … there is, therefore, an uncertainty, and a melancholy, in this embrace. It’s as though the Idea reaches out and grabs the Foster tune for a moment, and then having gathered it in, having added it to its world, turns around and looks back to the wider universe of notes from which it came; it looks with longing back at the universal from the specific.

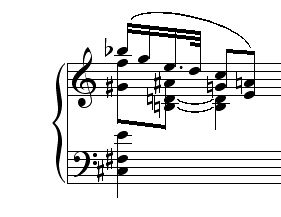

Can’t you imagine Beethoven, too, nearing the end of his life, looking back on all those classical style pieces, all the Mozart and Haydn that he knows, not to mention his own works … can’t you imagine, that those voluminous works must have (to some extent) blurred together for him? Indeed, interchangeability is just as key to the classical style as it is to the hymn: Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven all depended on parts that could be lifted from other pieces wholesale, they depended on patches of convention, on the expected recurrence of formulae. It is terribly easy to slip from one Mozart piano concerto to another if you are not careful. Oh, so you are writing a stormy piece in C minor? You might bring to mind your own early Trio, Op. 1, #3, or the 5th Symphony, or the 3rd Piano Concerto, or the Haydn Sonata in C minor, or some parts of The Creation, or Mozart K 491 or 415 or … goodness, there are so many C minor stormy pieces in the Classical Style, calling to each other, a clamoring din of C minor. This blurring must have been evident to him; it would in some ways have been terrifying to him (the death, the futility, of originality), but might also have suggested a new solution, a new possibility, an important aesthetic question. Why bother writing another long original theme in C minor, why add more to the pile, why bother trying to find something “original” at all? Is originality a dead end? Why not build your sturm-und-drang entirely on the tried-and-true; why not construct a theme so simple that it might almost be called generic? …

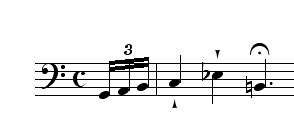

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

This idea (the Hauptmotive of Op. 111’s first movement) seems to me a kind of “symbol” or “stand-in” for stormy music … it is what happens if you just give up writing complex accumulations of details, if you say: why don’t we take all that as read, as assumed, and allow the cliché to stand for the whole? Why not expose the cliché at its root and see where that nakedness takes you? Because it is exhausting to keep having to write these great, sprawling masterpieces.

Now, you might say the essence of many C minor stormy works is distilled into this one motive. You might claim it has concision and that it has rediscovered classical purity, hallmarks of the late style. This would be the official version, the tour guide version. But does anyone else feel that this slightly misses the mark? Through this motive, Beethoven steps almost beyond concision to emptiness. For all its bluster, it is continually blowing its wad (forgive the expression). It gazes at the whole welter of C-minor-ness, and in summing it all up, casts at least a glance at the possibility that it’s all much ado about nothing: that all those C minor melodies, with their emphasis on chromatic slippage and diminished seventh chords, can add up to a sameness, a null set, a blur of generic angst. And Beethoven with one stroke makes this nothingness manifest, shows you the empty end of the road, and lays down a wall against it too: in the space where the specific is in danger of becoming a generic nothing, in the space where all the names and events and testaments of our lives begin to blur into the haze of the forgotten and the anonymous, because there is simply too much, too much to say, too much to remember.

At the concert that evening (I managed to escape the parking lot), when I got to the end of “Thoreau,” the last time that “Down in the cornfield” comes back, a very childish thing happened: my lip began to quiver, as though I were about to cry. Even while playing I had to confront this, this possibility of life cracking open, and raining on the illusion of the stage. I attempted quickly to diagnose myself. Was I tired? Had I taken my vitamins? There had, in fact, been something weirdly clouded and dreary about those two days in Bloomington, and perhaps I had ignored, repressed, stuffed the cause back in some closet somewhere … Can I fix this before the piece is over?, I wondered, idiotically.

I had the sense that I needed to figure out what the sadness was before the piece ended, otherwise I would never know. And I was right. There turned out not to be time, and applause killed it.

I think it was a specific Bloomington sadness. I am almost sure it was a memory of some humid lazy Bloomington night, maybe something was barbequed? like my psyche?, but it fled from the tip of my cortex back into the dark rustling cornfields of my subconscious. So I had a taste of it, it lingered at the edge of specificity, and then slipped back into the universal and general, into the whirlpool of the totality of my emotions about everything: but I must say those lingering moments, the seconds as the specific memory appeared and dissolved, were excruciating and amazing.

Behind the tune, there is the wider world of Tunes, and behind that simply the urge to sing; why should you add your specific tune to the ever-larger pile? Why indeed. But this process of extracting and sketching your specific tune from the world’s tunebook, and then—which is just the same act in reverse—losing it again, relinquishing it: well, this unending slippage from one state to the other is joyous, even though it sometimes feels melancholy, or Sisyphean.

At the far end of the concert, you’ll be relieved to know I had a totally different, wackier, feeling. Beethoven’s fugue had me again—this fugue is the diametric opposite, I think, maybe even the spiritual nemesis of the emptiness of the first movement of Op. 111—and it was sprawling around, tossing me about. I held on for the ride. I thought at some point “the Kroger parking lot probably used to be a cornfield.” And then, the scales: I grabbed innumerable carts and tried to stop them from damaging various cars and yet they kept racing away into the distances. While trying to stop them, I cheered for them. Go, contrapuntal voices, go, fly. Sing, and be free: if those two are not mutually contradictory …

17 Comments

The general idea has suddenly been flavored, or identified, shot through with specific self. But have we lost something by abandoning the general for the specific, have we limited ourselves? … there is, therefore, an uncertainty, and a melancholy, in this embrace. It’s as though the Idea reaches out and grabs the Foster tune for a moment, and then having gathered it in, having added it to its world, turns around and looks back to the wider universe of notes from which it came; it looks with longing back at the universal from the specific.

OMG—primal scream…

You didn’t REALLY tell someone you’d dump yogurt on them unless they came to your concert, did you???

Kudos to you if you did.

David Soyer told the story or hearing his teacher (I think it was Feuermann) play one of the Bach Suites for cello in a recital. After the recital some of his students asked if he had substituted one of the inner movements from one of the other Suites. He had no idea what they were talking about, and was unaware that he had played a movement from a totally different (but not SO different) piece.

Gahh! I LOVE your tone and your PIANO, Denk! Do a post on its specs?

Personally, I like yogurt absolutley plain. The fruit and whatnot is usually overly sweet and chemical and strange, even if it’s organic.

But then, when the yogurt is plain, the flavor of the yogurt comes out, and good plain yog is *so good.*

Of course, if you add honey or nuts or jam or fruit or whatever to the yogurt, you get something totally new- not plain dairy and not plain fruit. It’s a new thing (but like enough to the other yog-fruit iterations), too, everytime you make it.

Alas, to get good plain yogurt, you have to go to Bloomingfoods or Sahara Mart.

And, alas, I missed your concert in B-ton, but I heard it was really good.

i think your flavor should be coffee.

Yes, coffee it is. Done.

Jeremy Denk, Mochamerican Pianist who blogs, MPWB?

Suggestions welcome.

Suggestion:

Jeremy Denk,

transparent brilliance

interpreting

songs of God

and other composers,

Yes, coffee it is, generally speaking. But specifically, what else but Expresso!

oh, brent, how could you? expresso with an x?

I was at that Kroger on a Saturday evening a few weeks ago, and as I wheeled by the alcohol aisle there were some late teen-somethings fondling the bottles of Boone’s and Mike’s Hard Lemonade. I thought about buying them what they wanted, then reminded myself that it was illegal to do so, and flashed back to college when buying and drinking even the worst-tasting alcohol meant getting away with something, that an evening in Colorado Springs might yet hold some excitement. I was a little jealous that alcohol-buying and

other only-in-grownupland stuff was often more mundane than fun now, and felt a little older.

The recording I have of the third movement of the Hammerklavier renders it dull, but your flavor of it last Thursday evening took me somewhere deep in my psyche, and I’m still working through it all. And shouldn’t risotto fit somewhere in your flavoring, in addition to coffee?

Also: why doesn’t the School of Music put its world-famous alumni in first class on airplanes? There should be protests.

By the way… Nice sidebar on “memorisation” in the current issue of “Pianist”! Alas, no mention of Rice Krispie Treats or yogurt.

This was a fine post on Ives; I’m grateful to Renewable Music for pointing it out to me. It sends me back to a book unread for decades, Ermest Mew,am

s The Unconscious Beethoven, a book worth looking at. I like the idea of B**th*v*n blurring all that classical-style stuff late in his life; Op. 126 is a key to much of his music…

I am so moved by thinking about you almost crying. As you unflinchingly and beautifully write this narrative of performance, I wish I could have been there with you.

Thank you for posting the musical snippets… I enjoy your writing and your talent for analogy but my lack of training makes it difficult to follow your musical themes.

You shoulda’ dumped the yogurt on her head! 🙂

Hello there just stumbled upon your blog via Yahoo after I typed in, “Generic Stewed Prunes” or perhaps something similar (can’t quite remember exactly). In any case, I’m delighted I found it simply because your content is exactly what I’m looking for (writing a college paper) and I hope you don’t mind if I collect some information from here and I will of course credit you as the source. Thanks for your time.

2 Trackbacks

[…] Denkin aiemmista tuotoksista kannattaa lukea myös Schubertin suurta B-duuri- tai Charles Ivesin Concord-sonaattia koskevat […]

[…] updated, but when it is, insightful. A long time ago there was his post on the Ives’s Concord Sonata, which is deeply beautiful and moving in all the right ways–right before the big performance […]