The waiter sets a menu in front of you, and you realize, while he spills coffee into your saucer, that all the dilemmas of your life can be expressed in terms of oatmeal. You’ve learned that oatmeal makes for a wonderful day, draws out a sustained arc of energy and goodwill. But the craven eye wanders.

“Yes, that way lies happiness,” I say to myself, “and yet this way lies bacon.” Happiness seems, at that moment, such an unwelcomely long-term proposition. The seared, salty idea of bacon flashes in my mouth, fatty slab of the moment; whereas oatmeal squishes over into a digestive chain of planning and forethought, as if I were a stove and not a man. Am I to be fed to burn, or to burst forth in spurts of inspiration?

Consider the following. Josh and I watched a woman at the Newark baggage claim. The carousel was not crowded. And yet, when her bag dropped from the chute, the woman became a raving, rabid animal. She burst between us, bumping, nearly shoving, and then in her desperation to get that bag, at that moment … well, I felt that even her bag sensed she was in a hurry and revolted, sidled, twisted and turned in strange ways, so that she had a hell of a time getting it off the carousel, and nearly injured several of us “innocent” onlookers. (Don’t worry, Josh fans: He was unharmed!) We couldn’t believe it; the bag would have been there for her, three seconds later; it was not going to vanish; but she was unapologetic for her desperate urgency. Her bag, at that moment, was the great quest of her life, it was her Bacon, and if it was a misspent quest, so be it, she was proud of her idiotic bacon worship.

I watched the carousel spin on. I lifted my bag off it with smug nonchalance which no one noticed; I was proud of my idiocy, too. The humble, grinding, uncaring carousel whispered to me of hubris.

The ease of lifting the bag off the carousel—if the speed is constant, and there is no edge of desperation—reminded me quite strongly of certain moments of perfect preparation and anticipation playing the piano. Just the note, thock! into place. The woman struggling with her bag reminded me equally of certain moments of playing the piano, when you seize the moment, roughly, and the moment fights back.

Moments have all sorts of defense mechanisms against unreasonable seizure.

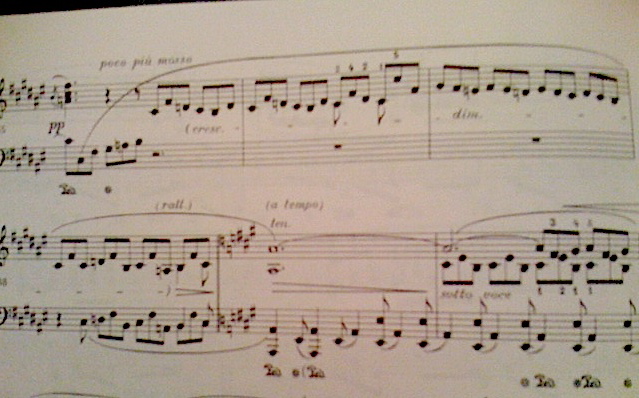

Confession. I chose to program the Chopin Barcarolle (last week in lovely San Diego!) on the strength of a moment I wanted to seize, on a juicy crispy piece of bacon I once smelled in its interior. Ah, I remember the moment well: a student came in to play the Barcarolle for me—a terrible, terrible student—but when she got to this moment I remember severing my lips from my grimy coffee-pacifier, and looking around the dismal basement room as if it were an alpine vista. “That’s so f&*() beautiful,” I said, regretting the word as it came out, but the student smiled at the silly professor. Here’s the moment …

At the birth of the moment, we have F# major and twelve-eight time, the delicious compound meter of the rocking boat. At the death of the moment: A major, and a faster tempo … the boat has entered a different, spellbinding current, the boat has been released into possibility. “Yes, the boat is floating along just fine, I say, it has been a delightful sail” but, then, after Chopin’s bacon-moment, you realize through the veil of your delight that there is delight and there is delight …

Chopin writes a passage of drift which allows one motion to become another, a flight between ratios, a mysterious differential equation.

This transition is amazing partly because of its disengagement, because of the sensation that the foundations of the narrative have been removed. This transition is not essentially “musical.” It does not conform to the niceties of musical discourse, it does not attempt to be the smooth unnoticeable gearshift. Chopin deliberately removes us from the world of capital-M Music, in which he had allowed us to bathe. The rich, melody-bass texture of the opening idea is gone. No more perfectly situated overtones; no more melodies in Italianate thirds and sixths: no, no, for you, listener, just a deliberately ascetic, spare single line: a cord, a lifeline, a narrow path of notes.

All the harmonic meaning has to be compressed, suddenly, into these few sinuous notes. Our brains must adjust.

Because Chopin has removed the foundations, because he is secretly rearranging the sails while we listen, we are reading the tablet of these barren notes without a lexicon. The rules that applied previously do not now; what we think we know lies to us. We know for instance that “we were in major, but now we’re in minor”—but this seemingly clear fact is a snare. The A-natural enters as a minor coloring of the major, but this guise is a pun, a deception, a mask … it is POSING as an emblem of minor, as a moment of sadness, darkness. But then the passage explodes—quietly, with the power of soft-spokenness—into the opposite, into A major (hopeful, radiant, expectant) …

The tone A is a platform for a deft pivot of meaning; it is this shift of meaning that adds the extra layer, the beauty past beauty. The A-natural, appearing first as a refutation of the warmth and joy of the opening material—a shiver down its spine—is really the proof of it; it is really a secret agent … to put it rather super-poetically… of luminous joy. This is something more profound than a “twist” or a “gotcha,” though it shares something in common with both of these … it’s like a meaning that passes through shades of light and dark, a word or a thought that hides in your subconscious, that comes out of the tunnel of the past, familiar and unexpected at once.

And there is more, more. The Barcarolle could be, if you like, a kind of essay in motion, in different kinds of motion (gliding, lilting motion … ) Now, the speed of motion is expressed as the ratio of two different entities

distance / time

… so, one way to mix things up, to vary the speed (the normal way) is to increase the distance you travel per unit of time; but the other way (the freaky way) to get at speed of motion is to call into question the very existence of time itself, to try to alter or erode the parcelling of units, seconds, beats. When Chopin steps into this transition, into the ascetic single line, one feels the sudden shiver of a lack … This shiver contains, I think, some sort of hidden imperative … it is as though he shushes you, tells you to wait … And then, by sticking to just the one voice (after all those luxurious voices) Chopin compels your continued attention; he continues to ask you to wait; he compels you to continue subtracting each moment, each note added to this chain, from the passage of Time, proper; he wants you to keep regarding each note as special, as suspended, as not-time, a process which extends not-time like a rubber band. Chopin says: each note that I add onto this chain I want you to subtract from time, and I want you, I expect you, to return to time only when I am done. It is a paradox, an immobile motion, wound between two different types of normal motion, a strange slice of removed time …

These two elements have a magical mixed effect. The “lie” of the minor key merges with the sense of not-time. Ambiguity plus falsehood: this is precisely the cocktail that made me curse happily at my student, and want to play this piece. Our honest attempts to seize time are not often rewarded. Time sneaks away, becomes difficult, clings to desires and other times, like baggage. But this passage suggests: fleeting moments might occasionally be seized through deceptions, which lead us—retrospectively—to the most beautiful truths.

I have been breathed in and out of so many airports in the last six weeks, I begin to feel like I should be stamped with a barcode, zipped up, and run through an X-ray machine: I have become acutely conscious of the inelegance of my passages. By moving so much, I become a thing, a crated item. When the baggage carousel grinds into life, buzzing and heaving, when the desk clerk at the hotel treats you with false, permanent cheer, when the hotel fitness room blinks back at you with its bank of TVs turned to news programs filled with prefabricated crap, political “discussion” that consists of idiots refuting idiots … all of these moments, in their monotony and convenience, are inelegant.

But Chopin’s motions: they are so meta-; they are simultaneously so precise and curvaceous; they are the elegant understanding of motion through music. They call attention to the touch of the hand, the very touching act itself, the “laying on of the hands”: they explore the interaction between the idea of touch, between the sensual element of touch, and the complex chromatic interstices of the harmonic world. To play these pieces is to be in touch (literally and figuratively) with elegance, the elegance of the motion of the hand corresponding to the elegance of the motion of the notes, each trying to find their perfect match, their perfect correspondence in each other. Motion that has nowhere to go, and everywhere to be: as if there were both a healthy Bacon and a dangerous, romantic, alluring Oatmeal sitting on your perfectly set table … as if you knew precisely how your day was going to go but had no idea what you were going to do …

5 Comments

And as my Oatmeal simmers away on the stove… Some semi-random musings of my own…

I think this may be the first time I’ve ever seen Music, most certainly Chopin, broken down into food groups, Bacon and Oatmeal. Protein and Carbs. Fat and Fiber. Obviously, the first thought that comes to my mind is Shakespeare’s: “If music be the food of love, play on.” Bon Appetit!

Your final sentence reminds me of a snorkeling trip in the Caribbean. As we were leaving the shore, we could see that we would be sailing through some rain, however, there was sunny, clearer weather on the other side of all of that dark. Racing through the storm, and being pelted by the cold rain drops was both dangerous and exhilarating – and since I had chosen to ride on the front of the boat in the open air, a little painful too. Once we reached the other side, it was like we had truly entered another world. Everything changed in an instant: the rain stopped, the sun appeared, and warmth was back in the air. And as I dove into the warm ocean…

Finally, that “f&*() beautiful” passage is truly “f&*() beautiful”. Even after repeated hearings – and “touchings” – it remains a wonderment. I had a similar reaction the first time I read thru Beethoven’s Opus 31, No. 3. When I played that first A-b6 chord, I thought I had misread it, or that it might have even been a misprint. And then continuing on through the first phrase that ends with that “squiggle”… Was Beethoven really that cool, hip? Yes. And he still is.

Say, there’s a fair amount of extra baggage in that edition you show of this amazing passage. Baggage that Chopin didn’t pack, I mean to say. The Barcarolle isn’t the easiest piece to edit (some big differences among the editions), but in this passage they all agree: no “rall.”, no “a tempo”, no “cresc.”, no “dim.”, and much less pedal in the A-major section. All of this would seem relevant to your (excellent) thoughts on the senses of time.

You can look at Chopin’s first editions at this fine site:

http://www.cfeo.org.uk/apps/

Beautiful writing as always, but I especially enjoyed the last two paragraphs. As a fellow musician, I can relate to the inelegant actions of travel that we endure only so those actions can be traded for moments of sensual touch, expression and elegance. Like the subtitle of your blog, colleagues often recount an all too familiar tale from the road and laugh about the ‘glamorous life’ of musicians. Thanks for sharing your inspired musings here.

Jeff,

Thanks for the wonderful link and the spot-on comment … Of course, “rall,” “a tempo,” “cresc.,” “dim,” are all in parentheses, as are the liberal pedal markings in the ensuing A major section … But parentheses are a sorry atonement for pushing a lot of interpretative crap onto Chopin’s music. Shame on me not to be more distrusting of my edition, and believing that a detailed editorial apparatus translates automatically into a “pure” edition. Shame on me and shame on Paderewski Edition … grrr!

Jeremy

Jeremy,

Yes, at least the Paderewski editors did us the courtesy of parentheses. Others are not always so kind!

Pianists are in a hard way for decent modern editions of the Barcarolle. The best of them currently available is hard to find: the New Polish National Edition, edited by Jan Ekier, does a pretty good job transmitting the complexity of the variants (look for Series A, vol. 12, published in 2002). Henle handles this complexity less well. Some of the best new Chopin editions are appearing with Peters London; when the Barcarolle volume eventually is published, it will definitely be worth a close look.

Jeff

One Trackback

[…] that way lies happiness,” I say to myself, “and yet this way lies bacon.” Happiness seems, at that moment, such an unwelcomely long-term proposition. The seared, […]