As a performer, I would like to play Every Piece Ever Written with The Most Conviction Ever so that people run weeping from the hall and change their lives and poverty ends and rainbows and leprechauns come sprouting from the earth and rivers run pink with Cosmos that never give you hangovers. But apparently this is unrealistic.

This last weekend, I found myself (on Saturday) playing the Tchaikovsky Trio and (on Sunday) the Brahms G major Violin Sonata. Now, these are two Romantic pieces that should never (ever!) be on the same program. I would say: even on the same weekend, it feels pretty dubious. They don’t make each other look good; they’d sneer across intermission at each other. It would be like casting Laura Linney and Al Pacino as lovers. I think it is clear that, of those two, Laura Linney would be Brahms (I loved her in You Can Count On Me, I’m a sentimental fool). Actually–now that I think of it–a biopic with Al Pacino as Tchaikovsky would be something to see. The subtlety and sensitivity he would bring to the question of the composer’s private life …

Tchaikovsky (like Pacino) has faith in that which is proclaimed (passionately enough, strongly enough, with inspiration); Brahms (like Linney) has faith in that which is hidden (craftily enough, subtly enough, with inspiration).

Both the Tchaikovsky Trio and the Brahms G major Sonata are incredibly moving pieces; they reach for the deepest kinds of emotions (the highest shelves, the purest groves). And yet, despite my best attempts at self-delusion, despite pumping myself up with Russian manly whatever, the Tchaikovsky leaves me cold somewhere inside (except for a few wonderful places), and the Brahms is like a best friend who I can call at 3 in the morning, when I can’t sleep, a friend from whom all you need is the timbre of their voice, a mere sound and cadence which quiets all the false fears of your life and helps you see things as they are.

It’s always fun to try to translate these deeply personal feelings into academic jargon.

Let’s consider the angle of MOTIVE. If the classical canon has a “shtick” it might be Motivic Development. Take a short musical idea and make the most of it (gratuitous pop culture reference: go “Medieval” on it); allow it to run through the whole story. Follow it up. Change it, but not completely. Thread things along, along the tightrope of the idea. Do what must be done to keep the motive alive … In the right hands the motive creates a riveting connectivity; in bumbling hands, we feel it is a mere talking point.

The Glory Days of the Motive, perhaps, rest with Beethoven; the Overtime period includes Tchaikovsky, when the Motive has seen better days; there is a difficult Renaissance with Schoenberg and company; and now, where is the Motive? It lounges around our postmodern landscape, waiting to make itself useful again. It’s working at a bookstore to make ends meet, advising people to read Schopenhauer.

Let’s have a thought experiment. Suppose you gave an class on How To Use A Motive. Brahms and Tchaikovsky are among your students. Tchaikovsky raises his hand quickly, throws out an idea:

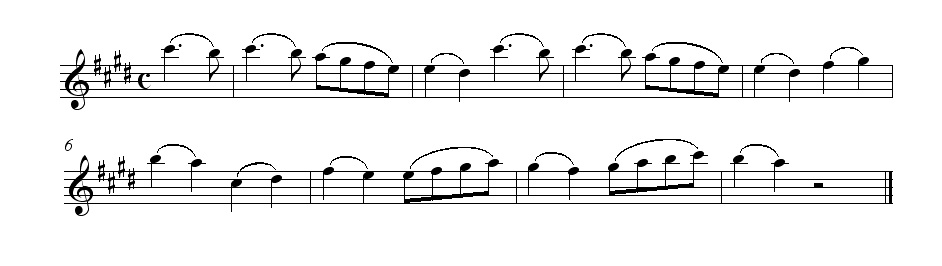

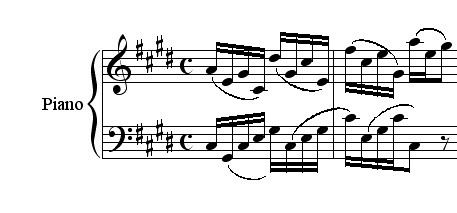

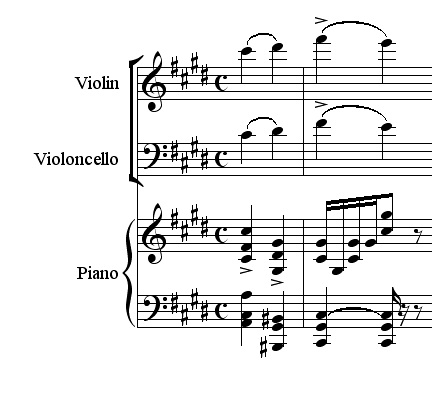

OK, it’s basic enough to be workable, but it has profile too. Good, you tell him: it’s a reasonable building block. Tchaikovsky follows upon this eagerly, he snatches up your scraps of approval, he says …

—Look, I extracted it from this preceding “love theme”:

—isn’t that the correct way to do it??? He beams. You don’t have the heart to tell him that, yes, that’s the “correct” way, but sometimes the correct way is pretty bad. He seems so happy with himself; you don’t want to spoil his fun; anyway, let’s see what he comes up with…

… a rushing piano arpeggio, which assembled from four bits of the motive—”clever”—sequencing up. We end up back at the same motive again …

and again, our piano variation …

By now you look at him with concern, like a borderline maniac, but he does it again …

and AGAIN…

… and then the strings “go medieval” on the idea …

This is what they mean when they say (those rascally musicologists) that the Romantics are sometimes “uncomfortable” with motive. At this point, you are like Matthew Broderick in Election (Reese Witherspoon as Tchaikovsky!); you regret even getting your teaching certificate; you want to head straight for the faculty lounge and drink a flask of cheap whisky and stick your head inside the microwave and turn it on, if that were possible. You can’t believe it, but Tchaikovsky’s not done yet—not even remotely—-you try to stop him!, but he’s going and going, pages and pages, and there’s nothing you can do … you look around the class, hopeless, helpless, hassled, harried, and Brahms is snickering in a corner.

Brahms doesn’t turn his assignment in on time. He has to think about it some more.

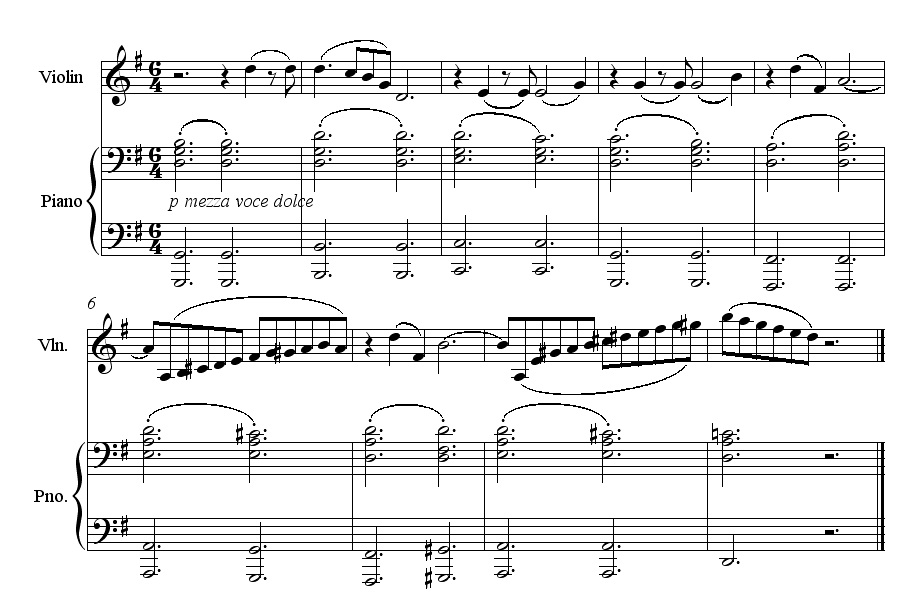

Next class, he modestly submits the following:

It’s been done before, you say. He says everything’s been done before. Hmm, well, you say, that idea’s pretty basic, it depends on what you do with it. He glances back at you tiredly, with calm contempt, a look that says Of course it does, it always does, you idiot. And then, the next class, he places this on the table:

Again, you want to resign your teaching certificate, but for very different reasons.

[To be continued!]

7 Comments

This is precisely why I cannot bear Tchaikovsky and positively adore Brahms only you managed to describe it far more accurately than my usual rolling of the eyes or empty superlatives. I’m already making my way over to the CD player to put the Brahms on for a listen.

Can’t wait to read the rest.

On Chopin, who solved the problem of the motif in his on way:

“With eyes averted, like a bride, the objective theme is safely guided through the dark forest of the self, through the torrential river of the passions….In Chopin paraphrase and doubtless every kind of associated virtuosity is the resigned expression of historical tact.” Adorno _Quasi una Fantasia_ “Motifs”

Damn that Adorno guy is good.

He can be, can’t he? I wonder how well he played the piano. One doesn’t usually associate him with Chopin, but the passage from which the quote was taken is wonderfully sympathetic and insightful. Do you suppose Chopin and Balzac ever met?

(I can’t believe you’ve got me interested in Balzac.)

Well colour me an ignorant philistine but i can’t make head nor tail out of that Adorno quote you’re all raving about. What on earth is an “expression of historical tact” ?

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on the Brahms and Tchaikovsky works. I love your writing!

Hello! came upon your blog from http://jeeleong.blogspot.com/

i really enjoyed this post, cos i’m a brahms fan, but didn’t study music and therefore don’t take too well to the formal sort of analysis you find in books etc. so this was great, cos it’s fun and readable. can’t wait for the next instalment. i’ve got the brahms played by heifetz, kogan, and szeryng, and now i can’t wait to go and listen to all of them again. 🙂

2 Trackbacks

[…] Thought Experiment […]

[…] what Brahms could have done to a motive like this, and I’m reminded of Jeremy Denk’s post(s) on Brahms and motives (and Tchaikovsky). And since the Fauré is kind of modal, I’m even […]