A certain cellist who shall remain nameless (but whose initials are those of a very popular magazine with a recurring swimsuit issue) seems to think Clara Schumann may have not been a very nice person. I cannot supply a transcript of the late night discussion here, for reasons of decency. The Great Clara Debate, pro or con, rages on, as if we are somehow angry with Music History for allowing two of our Favorite Guys to fall in love with the same Controlling Woman.

However, I was shifting somewhat Pro-Clara (doesn’t that sound like a shampoo?), while playing her husband’s piano quartet.

Clause one of the universal indictment: she applied pressure to her husband, encouraging him to write in classical forms (sonata etc.) when his genius was suited to a more radical reinvention of form: to shorter pieces linked in chains, or some other solution which he might have found if only Clara hadn’t been such a stickler. This indictment is irrefutably founded on hypotheticals. I too am impossibly seduced by what Schumann might have written. Yes, we have Davidsbündlertänze, we have Carnaval, and the strange sonata amalgam of the Fantasy … but don’t you sometimes catch yourself imagining some even more revolutionary work, in which Schumann’s tremendous imagination dissolves the whole Narrative Ethos of Western Music into heartrending fragments, in which one no longer longs for, no longer requires coherence? Something which would have ended the whole infantile fetishization of Sonata Form, which at times debilitated even the greatest Romantics? I do.

Rufus Wainwright has something to say about Schumann; he just came on the Starbucks soundtrack here in Paddington … but I can’t quite translate the message …

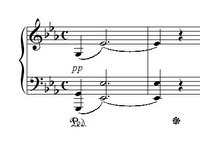

But let’s consider another tantalizing hypothetical: without Clara’s pushing Robert might never have pondered in depth the delicate “fantasization” of the Classical harmonic world. Sitting in Prussia Cove, I find myself close to the place in my brain I inhabit when I am in love (substituting music as so often for elusive reality), listening to the unfolding opening of the Piano Quartet. The strings play E-flats, and the piano plays an ascending sixth:

This resounding sixth, made blurry totality by the held pedal … a fantastic otherworldly sound, predicated on the simplest proposition: the first note, the bass, is not the root of the chord, but its third. Why couldn’t other composers think of that bar? Something Brahms only rarely (if ever) learned to do: make the first bar an “extra” bar, an unnecessary item, a non-event depending on how you count events — a bar for listening, not telling (Beethoven slow movement of Hammerklavier opening). A bar in which semantic space is opened, not defined.

The pedal and the ascent from the deep bass–the bass which refuses to go away just yet, at least not until we have truly heard it–is a Romantic symbol, connoting space, aura: as if E-flat major (that most classical, refined, elevated of keys) were echoed off something greater, were the mere worldly reverberation of a more profound spiritual force. (Pedal: echo, overtone, undampened string, vibration.) E-flat has arrived from somewhere; the piano suggests somehow the existence of this other place without being able, in music, to show it. Incredibly, the phrase that the strings play in response to this enigma could easily be an opening by Mozart/Beethoven/Haydn–simple, textbook, linear, architectural, tonic-to-dominant.

The Classical Phrase is thus “born” out of the sound of E-flat major, out of the pedalled ambiguity. Classical clarity has been reframed, resituated–in the context, perhaps, of pure sound. (Schumann’s opening bar implores us to hear sound as sound, not as discourse.)

The opening, “listening,” bar is Romantic enigma, and the next two bars are pure Classicism; the slow introduction is a gentle (but absolutely riveting) dialogue between these tendencies: not a competition between them but an interlacing, in which fantasy and phrase (yearning and definition) use each other as points of reference, to supply each other’s lack.

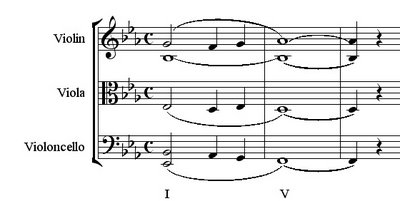

So, too, the opening of the ensuing Allegro non troppo. Schumann launches us with what could be a classical antecedent:

but then composes a strange, spinning, asymmetrical consequent:

There is no way to know when the piano will finish; the chain of notes is endless, undelineating and undelineated, as if the pianist is simply lost in the idea, in the joyful setting-forth. So: in place of the answered question, we get a wandering curlicue. Schumann adores placing the ungrammatical in the grammatical niche, sticking an adjective where the verb must be. In this case, no resolution of the dominant seventh … simply an elaboration of it, a giant Romantic ornament.

Somehow, Schumann’s cross-pollination of Classic and Romantic maintains a Mozartean transparency, a charm and elegance. The junctures are strange but not jolting. In the Piano Quartet he provides Romanticism without decadence or decay, in joyful, prideless, humorous possession of aesthetic discoveries, not collapsed into struggle or conflict or any kind of despair or confusion. In other words: a high water point, a magical moment in Music History. Where would all this be without Clara? Unanswerable question. Schumann’s encounter (in this case) with classical form produces an unbelievable and delicate fusion, a kind of perfection in which the gushing Romantic is not at all tiresome in his teenage accesses of passion and does not wear himself out yearning but makes his passionate singing useful to the adult world. He refutes Rilke’s annoying, pretentious Zen-ishness:

Song, as you have taught it, is not desire,

not wooing any grace that can be achieved;

song is reality…

Young man,

it is not your loving, even if your mouth

was forced wide open by your own voice–learn

to forget that passionate music. It will end.

He (Robert Schumann) says: Rainer, I prefer not to forget that passionate music. I am a young man loving, and I will woo, and achieve grace. Which is why I (Jeremy Denk) will–for the moment–defend Clara from the besmirching hand, and live for a few more days with Schumann’s magical-classical E-flat major (like magical realism), and not so much with Rilke’s melancholy, oh-so-enlightened, resigned “reality.” Schumann’s passionate music does not seem yet to have found its end, so there.

8 Comments

jdenk, if bees have knees, you are it! rufus was probably singing “my phone’s on vibrate for you.” it sort-of-almost-quasi-inverts the opening of the third mvt tune in a finlandian sort of way, doesn’t it? maybe poor schumann would have written a tune over a latin bass, had clara been a little less noise, little more funk.

love!

jstumm

Shubert busts his brain but I didn’t know Rufus ever had anything to say about Schumann…

who knew rufus had so much flexibility? i love his judy garland concert recital (not impersonation) at carnegie hall.

good for clara schumann, there’s usually a good, strong woman behind every man’s instrument.

Hmmm…agreed, musically. But historically you’re a little off: Clara didn’t necessarily urge Schumann to write in classical forms. In fact, she tried to discourage him from writing string quartets, for instance, because she thought he wouldn’t know enough. Ironic, since in fact it was he who taught her about classical forms, far more than vice versa. Besides, he composed as he wanted – and stopped showing his music to Clara as he got further and further into his own magical world, and flet she couldn’t follow. So that’s really not a valid accusation against Clara – there are many others… Best wishes from Sports Illustrated (!)

so, bozo, is clara is this year’s Swimsuit Issue?

Like anonym 7:50 am said there are many other accusations against Clara.

One musicologist and feminist who worked on a biography on her said in an interview first she was excited about her subject but the more she worked on sources the more she found Clara to have a dislikable personality and was very glad when the work was finished.

The biggest one is that C. treated her kids quite bad, that she cut communication – maybe she simply wasn’t interested in them – at least not as much as in what she herself did on stage.

Before her marriage she showed no hint of taste and musical reason because she preferred to play shallow virtuoso pieces to pieces with substance: she simply didn’t understand them. If I had been Robert I would have been much more miffed by her ignorance. Marriage? Heaven forbid!

But maybe she looked gorgeous or was hot in bed. >sigh< BTW I LOVE Eflat-Maj pianoquartet; I usually melt in the slow movement. There is also a good arrangement for two pianos by Mr Brahms.

in response to Anon 3:28pm and in Clara’s defense as a pianist–everyone played shallow virtuoso pieces when she began touring, but she was also the first pianist to program Beethoven’s “Appassionata” Sonata–at the age of 15, I think. There is no doubt that she learned a great deal from Robert and matured musically under his influence, but I find it hard to fault her as a pianist in her day.

Sports Illustrated – rofl!

Hi Sports, I hope I’ll soon have the chance to hear you again playing fine Schumann chamber music with your Illustrious friends. 😉