I was doing the dishes the other day (applause, applause) when jealousy struck. Boredom and prune fingers are more typical side-effects. It was because Nina Simone was singing “The Pusher” in the other room (from her Blues album), and she’d just got to that place where she says “the pusher is a MONSTER!!!!!” It’s a great place. Her voice (never lush) passes over into this astringent yowl, the honk of an existentialist goose; it buzzes and grates; the pitch wobbles but somehow sticks to its fabulously ugly spot. Yes, Nina, the pusher is a monster. (What sort of monster? The sort that would consent to sing like that.)

Now, the source of my jealousy: where in the classical rep can you really “let go” like that? Where can you howl and yowl and curse the very ground you walk on? (Metaphorically speaking.) I will allow that such a wonderfully expressive, sustained sound, growing and shifting like an amoeba, is not really possible at the piano. But are there similar places, where one aims for the wild and untamed. The first example that came to mind wasn’t so good: near the end of the Strauss Violin Sonata, 1st movement, both players indulge themselves in a huge, operatic climax; it goes on and on and on, in waves, arpeggios… sigh. Yes, you “go to town;” but it’s a clean town, sort of like Columbus, Ohio, or worse yet, Lake Forest, Illinois, with its faint, unappetizing whiff of elitism and polish and pride. Not that I’m complaining; I always enjoy playing the Strauss Sonata, and I certainly get my jollies during that moment; but it’s not like Nina’s “monster.”

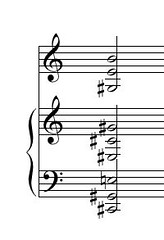

The second example I thought of was better: the final chord of the Bartok 1st Violin Sonata. It’s a giant, wonderful splat:

Sometimes audiences are a bit thrown by this chord, the conflation of three “normal” chords. It’s not that there’s no harmony to deal with… there are too many harmonies to deal with, all in bluesy, dissonant relation to each other. I myself imagine Bartok (or the ghost of Bartok) saying, right afterwards, “that, my friends, was the TONIC,” with a wicked, joyous smile which bursts into a cackle as he walks off into the night. He doesn’t stick around for the puzzled applause. The real Bartok was probably too earnest for this, but who knows?

I end up thinking also about how at the end of the Nina Simone tracks there’s applause, but through the applause the pianist and various other instrumentalists just kind of “go to town,” as if letting free certain ideas which they had wanted to play during the actual tune… The pianist riffs up and down, crazily, and it all seems to be a transition to the next piece, a moment of liberated musical time, as opposed to the more structured time of the songs themselves. Of course, in the classical world, these in-between moments are known as “uncomfortable silence,” during which people make catty or complimentary comments about what they just heard; during which girlfriends ask their boyfriends what they thought, and boyfriends try to think of something to say; during which programs are crumpled and uncrumpled, and really only repressed coughs are let free. In classical music the boundary between piece and non-piece is very rigid.

I think if the ghosts of composers do show up occasionally at concerts, they usually leave before the applause starts. In fact, they’re probably making their way to the door during the final measures, hoping to time their exits exactly with the last moment of the piece (and if they’re in Carnegie Hall, they probably have to fight with a considerable number of eager home-bound New Yorkers in the process). This isn’t because they hate the performer, or the attention he/she is getting, It is because they envision the ends of their pieces are exits in and of themselves, and they don’t want to let those exits get stale and overcooked. I often feel the end of a (good) performance as the beginning of a larger momentum, as inspiration to go and do and be fruitful and multiply etc. etc. In fact, come to think of it, I never think of the ending of a piece as a closure, or stoppage, as a dead end; the more satisfying the ending, the more of a beginning it seems.

Lest I get all skewered on this simplistic idea that jazz lets go, while classical holds in (jazz=freedom/classical=repression)… in which I am incidentally a repressive figure… I was noticing the ways in which the blues template “holds in” some of the extremities of meaning which the singer declaims. In “The Pusher” Nina says some pretty outrageous stuff:

If I was the President, hear me,

of this land

I’d declare total war

on the Pusher man

I’d shoot him if he stands still

I’d cut him if he runs

I’d kill him with Bible, my razor, and my gun.

And yet somehow these words don’t feel so violent on record as they appear, written on the page. The recurring pattern, the blues syntax, seems to take the message out of itself, to displace it. It’s still, after all, only the blues, the music seems to say; the chord changes (which never change) make it OK; the violence of the words is only “musical,” a kind of expression of rage celebrated (there is something celebratory about this song, though it is about a tragic subject… is it celebrating the musical catharsis, the very existence of an acceptable expression of this rage?) In many classical songs, in those of Mahler for example, there is no such reassurance. The music is almost too responsive, will accommodate and mirror the wildest words. And when Schubert, at the end of Winterreise, shifts to a skeletal, nearly non-song, the barest, saddest outline of a hurdy-gurdy with only a few notes to play, he ups the ante even further, he almost renounces composition itself, he says “I give up, and you should too.” There is no comfort, anywhere; the aimless patterning is totally unconsoling, amusical, music writing out its own demise. That’s how far the classical world is willing to take it.

So I take it back. No need to be jealous. “My” repertoire goes to all sorts of extremes. So there. But if you see the ghost of Bartok (perhaps having martinis at the Redeye Grill after some concert or other), tell him thank you for me, I love his dirty chords, that he brought over from folk songs to classical, civilized climes. I love that I can play them and feel dirty, their rough feel in the ear and the hand, the naughty thrill of sinking into one of those “ugly” chords before a mildly tolerant audience, and (especially) that I don’t even have to clean up afterwards.

4 Comments

Jazz that doesn’t “let go”: Lennie Tristano.

If you haven’t heard any yet:

Go here.

Nice blog…

mem

Oops, here’s the Permalink:

http://offbeater.blogspot.com/2005/08/temporary-beauty.html

mem

yay bartok!

ooo that chord looks absolutely delicious! *writes chord on music paper and runs to piano to play it*

…

oooo that is good well it’s bartok what do you expect?

“I myself imagine Bartok (or the ghost of Bartok) saying, right afterwards, “that, my friends, was the TONIC,” with a wicked, joyous smile which bursts into a cackle as he walks off into the night.”

hahahahahhahaha and that’s only the tonic! what about the dominant and the mediant and everything else? muahahaha! evil, but genius

When I read that, as ever, magnificent and thought provoking entry, my first thought was to try and think of some jazz as bleak, just out of some sort of spirit of competitiveness. Much as I love jazz and classical music (if you like, you can imagine all sorts of cliches here about artificial and contrived boundaries between genres of music that exist only so people can put it in managable boxes and not, heaven forbid, think too hard about it. Possible superfluous Duke Ellington quote about how there are only two types of music, good and bad), I’ve always felt the need to fight jazz’s corner, largely because that’s the position I usually take in musical arguments with my dad – jazz is my world, classical is his.

It was a struggle, and I know my jazz. Even at the most harrowing moments of Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, there’s always the soaring alto sax of hope round the corner to cut through the churning seas of anger and despair, even if it is frequently tinted with a delicious melancholy. I think maybe sometimes Bud Powell approaches it, starting beautiful cascading lines only to sabotage them mid-flow as if to say ‘well, why bother?’, but it’s not really the same sort of giving up, I see it as being troubled, deeply troubled, but not really resigned.

That was a lot less interesting than I’d hoped, but I’m dosed up on some nicely numbing scotch, so I’m damned if I’m not submitting it.