As I draw the last coffee cup out of my cupboard I sigh and note that these thoughts do not want to end. Apologies for length and ramble. Perhaps a lunch break could help?

…

I admit I’m a snob who sometimes, but not always, sneezes at Rachmaninoff. Is it that it seems too easy for him to whip up a climax? And the peaks seem too clear, too etched, too predictably prolonged? The other night, at the Harry Potter movie, I winced when the strings swelled, smothering a sugary soliloquy in redundant syrup. My ears, my ears! They alone would not exculpate this excess. I often wish I, or anyone, could come up with hard and fast rules, for when something will be “too much”: rules of taste, which one could mail to Hollywood producers, to Oprah, to nightly news programs covering hurricanes, etc. But for whose sake do I wish this? Probably just mine: to save myself irritation, to avert the desire to avert my gaze, to quell my urge to flee the theatre, spilling popcorn, Pepsi, Junior Mints–what have you–in my headlong, heedless escape.

Climaxes are dangerous places, like peaks of mountains, I suppose, where a wrong step is extremely costly… places moreover “earned” with slow assiduous steps. Ugh: even stating this need to “earn” a climax, I feel like a fuddy-duddy in a leather armchair who earned success “the old-fashioned way.”

The other morning I came to the climax (my climax) of W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz, in the living room of a friend, and while he busied himself emptying the dishwasher and concocting frightening smoothies I was frozen unhelpfully on the couch, in that uncomfortable, antisocial position you assume when you are really paying attention (or trying to). I read this book a year or two ago, admired it, but had forgotten nearly everything about it … except just a few odd details and scraps. If I had forgotten it, how good could it be? But: “it is precisely because we forget that we read.” (Roland Barthes). And also Barthes: “those who do not reread are condemned to read the same story over and over again.”

And so: I attacked the book again. Again admirable, with a continuity and intensity of thought like a leash, dragging me places where I didn’t necessarily want to go. But I had skeptical thoughts, along these lines: It is a Holocaust novel; the story it tells, rather indirectly, is a well that has been dipped into often, sometimes invoking (exploiting?) pathos from history without earning it, so to speak, artistically. What new could one bring to this story?; has the novel’s overwhelming sadness and sense of alienation been “earned,” or simply referred to history, which is supposed to justify it? And I had other problems: a passage depicting the beauties of moths in Wales, for instance, began to seem long; there were seemingly aimless lists of flowers, animals, incidents; and I at times awaited a payoff, which is no way to read.

Locating the climax of Austerlitz would be difficult; it is long, to be sure; but it seems to begin when the narrator goes into a dusty corner of a railway station, purely by chance, and begins to realize that this is where he arrived, many years ago, in 1939, a refugee from Prague, sent to England in a last-ditch effort by desperate, doomed Jewish parents. The climax begins there, but continues, and continues, with a slow decoding of past, fact, identity… the narrator goes back to Prague, meets his childhood babysitter, discovers the names and lives of his parents, retraces his escaping steps, and begins to make sense of all the haunting images of his lost years, to understand why certain sensory data were so important to him.

Ah yes, all the miscellaneous data from earlier now click into place! They were brought to our attention because, and because … Whew, the novel begins to solve itself, like an automated puzzle. But the emotional problem is not solved. Left behind, as a sense of sad history and fact erodes the sad emptiness of the first half of the novel, is still the unshakable alienation of the narrator–stronger than revelation or discovery. And it is this that allows Sebald to sustain the tension (a very musical novel), to bring the climax toward a second wave. Though the symbols of the novel have been “explained,” they still circle, forming various storms, configurations, nebulae… why won’t they stop?

I guess I felt the “real climax” to arrive around here:

In one of the empty spaces not far from the station … the Bastiani Traveling Circus had erected its small tent, much mended and wreathed in strings of orange electric lights. By tacit agreement, we entered just as the performance was coming to a close. A few dozen women and children were seated on low stools round the ring… We were just in time for the last number, featuring a conjuror in a dark blue cloak who produced from his top hat a bantam cockerel with wonderfully colored plumage …

After the conjuror’s exit the lights slowly dimmed, and when our eyes were used to the darkness we saw a quantity of stars traced in luminous paint inside the top of the tent, giving the impression that we were really out of doors. We were still looking up with a certain sense of awe at this artificial firmament which, as I recollect, said Austerlitz, was almost close enough for us to touch its lower rim, when the whole circus troupe came in one by one, the conjuror and his wife, who was very beautiful, with their equally beautiful, black-haired children, the last of them carrying a lantern and accompanied by a snow-white goose. Each of these artistes had a musical instrument. If I remember correctly, said Austerlitz, they played a transverse flute, a rather battered tuba, a drum, a bandoneon, and a fiddle, and they all wore Oriental clothing with long, fur-edged cloaks, while the men had pale green turbans on their heads. At a signal between themselves they began playing in a restrained yet penetrating manner which, although or perhaps because I have been left almost untouched by any kind of music all my life, affected me profoundly from the very first bar …

I still do not understand… what was happening within me as I listened to this extraordinarily foreign nocturnal music conjured out of thin air, so to speak, by the circus performers with their slightly out-of-tune instruments, nor could I have said at the time whether my heart was contracting in pain or expanding with happiness for the first time in my life . Why certain tonal colors, subtleties of key, and syncopations can take such a hold on the mind is something that an entirely unmusical person like myself can never understand, said Austerlitz, but today, looking back, it seems to me as if the mystery which touched me at the time was summed up in the image of the snow-white goose standing motionless and steadfast among the musicians as long as they played. Neck craning forward slightly, pale eyelids slightly lowered, it listened there in the tent beneath that shimmering firmament of painted stars until the last notes had died away, as if it knew its own future and the fate of its present companions.

As a musician, the goose got me (earned my attention). The sudden opening of Austerlitz’s musical nerve played on my inner strings (me, whose musical nerve is always TOO open). Sebald creates this circus, suddenly, out of thin air–this musical, unrecorded, provisional moment–simply to destroy it, in order that in the following pages we can see the massive Bibliotheque Nationale erected upon the spot of this bizarre performance, in order that one priceless moment for one individual can (in a recurring cycle of humanity) be replaced by an enormous vault of bureaucratically organized information. Preservation=destruction? Earlier discussions of futile fortifications, the compulsive architecture and organization of German concentration camps, etc. all suddenly rush in (flood in)–this sense of “rushing,” of symbols coming from every direction, makes the moment climactic for me–and these earlier “dispassionate” architectural conversations become relevant, with the appearance of this library, with its monumental style, four towers, arcades and staircases, forbidding easy access to information, which it holds and buries. (A building with an odd resemblance to Juilliard.) So that: the book is not about the death of the narrator’s mother, nor his father, nor any of these countless human destructions or violences … it is now just about a single goose’s look, squashed under tons of archives.

Aha, climax: one odd symbol becomes the eye of the hurricane around which all the others suddenly organize. Factoids from previous pages swarmed before my eyes; I was overwhelmed by the book “as a whole.” I sipped gallons of coffee unaware; my foot fell asleep. And in the aftermath, (after the goose is cooked), the book falls apart, ends in fragments. This climax is a confluence of creating and destroying, a kind of willful evil of the novelist. We do not mind that the author destroys what he creates, this does not seem immoral?

So earlier I had a metaphor for climax-as-place: a peak of a mountain, say. And now I have climax-as-force–as a nexus of symbolic energy.

What occurred to me later that day, as I was towelling off from one of my long long showers in which I dread the cold of the non-shower world, was the idea of climax as singularity, the way a point in time or a set of words or an image becomes a center, a reference (in this a climax is like a symbol); though we would like a climax (like a shower) to sprawl, by its nature it is ephemeral, and the question is always prolongation, enjoyment, sustainability.

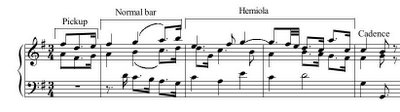

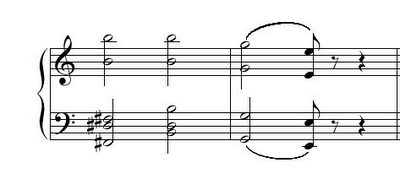

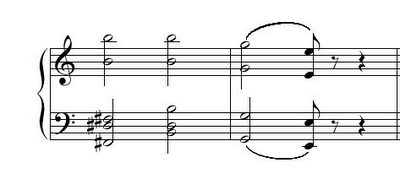

A lot of the musical climaxes I feel squeamish about are about “pouring over,” about excessive enjoyment; they “cling.” Sometimes they outlive their moments, they outstay their welcomes. And they are focused to a point, like a lens: a few measures of unbelievable volume or intensity, against which all other points in the piece can be measured. But there are other kinds of climaxes, more like Sebald’s goose. I am thinking right now of the Schubert Sonata, Op. 143 (which I warily remind myself I must play in Washington in April, alongside Winterreise): the exposition of the first movement. This piece begins in a very serious, overtly tragic “A minor mood,” almost too much so, like someone who makes a show of his sadness, (like Austerlitz), in fragmented, lamenting phrases strangely suggestive of Russian Volga boat songs. These tragic fragments seem to not quite know what to do with themselves (like Austerlitz), they keep ending up in this rather unremarkable tag:

Can this tag become a climax? It tries to hoist itself up, but fails; there is a great deal of ominous, boiling rhetoric; tremolos, slippages, a loud explosion; then two soft chords, and then … then the unbelievable happens:

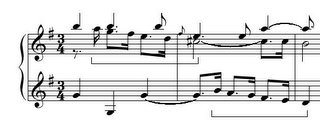

Unbelievable because Schubert caused us not to believe in E major until this moment. The piece, to this point, has resided convincingly in a certain sound-world, an emotional province; though we may not have noticed, its boundaries have rigorously excluded certain kinds of voicings, nuances (certain very “technical” musical things); have excluded a lot. And when this new theme (why do we need to call it this annoying name “2nd Theme”?) appears, with its close, tender harmonizations, its suggestion of a men’s chorus, or a slow dance, or a folk tune–so many possible associations come to mind–the exclusion is lifted; and in this absence the emptiness of the previous music becomes evident, and a space is opened for something else to rush in. After the first sense of disbelief (I am always amazed by this theme), I definitely feel that rushing, the theme’s web of associations, symbols from afar, an awakening. (Austerlitz’s musical sense is suddenly awakened by the mysterious Eastern music of the circus troupe.) Though there are no sweeping gestures, though it is uttered quietly, inwardly, pianissimo, though not in any way traditionally climactic, this passage is a climax. It does not pour over, exude, or demonstrate; instead it draws energy into itself, retracts, concentrates.

This melody is crafted around a single note, E–the inescapable note, the immovable object. Notice the intensities Schubert can weave around this pedal, this pivot; about what he can do despite–or because of–the limitation of that singularity. (Climax as singularity, as concentration into a point.) Everything is E, we are tied to that note, all of our energies must be drawn within that circle of attention; I feel that theme, with its “limitation,” as a bubble, as an enclosed space, a created paradise which Schubert, like Sebald, will destroy.

What does Sebald’s goose symbolize? It knows, he says, the fates of all the people around it; these fates are probably death, dispersion, erasure; replacement by a soulless monumental library. And yet the goose looks and listens, “motionless and steadfast,” its neck craning in concentration; it is a symbol not necessarily of what-is-known but perhaps just the knowing, the perceiving, itself. If the listening goose is just about the vanishing, then why tell its story at all? Why would Sebald choose as a symbol of the music (itself a symbol, and on and on in an endless chain) something which emits no sound whatsoever? I am reminded of the wonderful Ives quote “My God! What does sound have to do with Music”? Which is ridiculous but true. And also I’d add: what does volume have to do with climax? or climax with plot? or emotional closure with knowledge? All of these can be uncoupled, recoupled, rethought. Let me mail this to Oprah. I will mail her, and the Harry Potter people, that scene in Pnin where Nabokov manages a climax with one elderly man washing his dishes, alone.

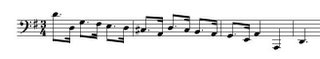

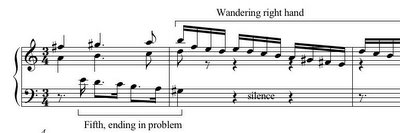

In the first part of the exposition, Schubert’s tragic muse keeps exploring the relationship between the tonic and the subdominant … a common neighbor motion, become a plagal obsession. (This is part of what makes it sound vaguely “Russian.”) And lo and behold, the second theme, at its outset, presents us with the same motion: I-IV, transformed. There is nothing to this. There is so little composition, so little sense of craft: just the sudden existence of this same neighbor motion, in the major key. (But so beautiful!) So that I have the feeling that Schubert has not created this moment, but has evoked it, simply by listening, by paying attention: by “knowing the fates of the participants.” I-IV is capable of tragic fates, yes, but what about … He stares out at us, neck craning, concentrating, hearing the harmonies of the music around him, hearing the new major key take shape; at that moment he seems not to compose, not to demonstrate or perform, but instead to listen, remember, perceive.