When people ask me about “how exciting” being a pianist is, I tend to be a jerk. I reply with stupid things, the mere accessories of the trade: the monotony of hotel rooms and airport lounges; the Sisyphean accumulation of frequent flyer miles; the little voice inside that whispers in your brain that you could always practice more, more, more.

Sometimes I’m a jerk for virtuous reasons: someone has just shared with me how boring their job is, how much they hate it, and they ask me, with a weird light in their eyes, what it’s like being a pianist. This happens on dates. And I try to reasonably downplay the pleasures of a musical career, with the hope that I don’t sound false. Probably other times I’m a jerk for jerk’s sake, because I’m impatient, or because I’m lazy. Maybe I’m in one of those moods where I imagine that that which I truly love cannot be shared. Anyway–do people really want to hear?

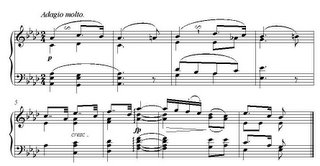

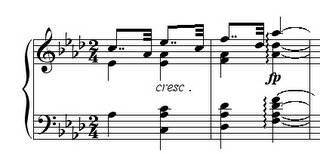

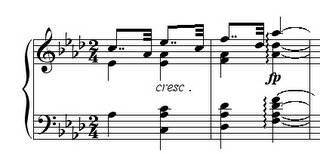

Yesterday I came back from a late, lonesome lunch at the ubiquitous Saigon Grill; I did not take off my coat; but sat down at the piano with a plain lust for the following measures:

I played them several times; wrote in fingerings (soon to be corrected, changed); tried to connect my brain more definitely to the tips of my fingers; contemplated the shaping and timing of the turn; and then–shamelessly–skipped to the coda. I am only human! I admit sometimes I just want to skip to the “good parts.” As much as I wish I could, I do not always enjoy every piece equally at every moment; I have weaknesses for certain moments and I build my conceptions around them, toward them. But, I tell myself, Beethoven must have built his conception towards this coda too. How could he not? I often enjoy thinking about the pride composers must have felt at having written certain passages; even they were pleased, even their impossible standards were met.

As I played the coda, I felt guilty. Not for skipping to it; but because I needed to accomplish “something useful” before I gave myself this searing pleasure. In a flash, I recalled my former teacher, Gyorgy Sebok, impeccably dressed–having parked, as always, illegally in the loading zone–walking into a lesson I had with him, saying that he had just vacuumed the house, and that it made him “feel useful.” He smiled his European, utterly cultured smile, which commented ironically all at once on the vacuum, on himself vacuuming, and on the very idea of usefulness. The incomparable guru finding himself useless, sucking up dust.

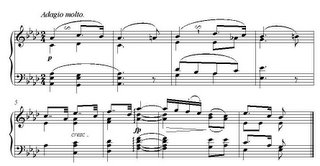

So, I tore myself away from the piano and I hauled the Hoover out of the closet and cursed its non-retractable cord and cursed the astonishingly outdated electrical systems of my building, and cursed the red carpet I put in the piano room, which seems to put an exclamation point on every morsel of dirt it collects…. and thus cursing, I did a serviceable job. With the unpleasant Hoover smell lingering in my nostrils, making me want to cough, I removed my coat and sat down at the piano, calmed by the carpet’s clarity. Now I took on the coda in earnest. This slow movement is a difficult, painstaking narrative, in that we have to follow (Beethoven unravels) the same long thread twice: he makes us re-experience the same sequence of events with only a small modification the second go-around. It tests our patience, or at least it tests mine.

I hate formal diagrams, but sometimes I succumb to them. Here’s what I’m talking about:

A … transition … B …

A … transition … B …

And by this point most of the movement is over. So you had better like A and B. I’m fond of A and B (though I prefer to refer to them by their “real names”), but I have to admit they’re “not enough” for me. As beautiful as they are, they are kind of naked; they are sparely scored; Beethoven is testing the limits of how few notes he can get away with, how little material he can use to fill out a large space. This is not a weakness! I remind myself as I play and try to find lots to love in A and B, but even as I am adoring these materials I heed the craving they create. What’s missing? When will I not feel I am filling in the spaces left by the composer? To be fair, I think A and B are not “missing anything;” they are trying to express something-like-this; they are a symbol of spareness; their existence defines a void which must be filled.

When I had to grade students’ papers at Indiana University, I would anticipate with horror the concluding paragraphs, which would inevitably begin “In conclusion,” or “Summing up,” or etc. It’s true, the student had usually made all the points he/she had to make by that point, and there was no escape except through redundancy. Some sense of finality was necessary; how else could the paper be over? And don’t get me wrong; I was as glad as the student that the paper was over. But how do you say again what has been said, while not just saying it again? I would ponder this imponderable while gleefully crossing out their final paragraphs: “said that already,” I would helpfully inscribe.

Let’s be boring for another moment and establish that theme A has a certain pattern to it:

Short. Short. Long.

OR

a a b

OR

Idea. (Responding) Idea. Arc.

In this pattern, the third time’s the charm. Though the first two segments (short, short) establish the crucial “grammar” of the theme–a dialectical rhythm–the third segment (long) provides a paradox: it simultaneously functions as a symmetrical, rounding idea (being exactly as long as the preceding two segments combined), as conforming filler, and on the other hand functions as a force for the unexpected and new: it sends the whole musical paragraph in search of some meaning or goal.

Let’s say, then, that the very structure of A–its one-two-three punch, which we have now analyzed so heartlessly– has some serious semantic baggage. I might even say it has a personality, a way-of-being.

At first glance, Beethoven’s coda falls into the “said that already” trap, because: here comes A again, for a third time. But it is a bit different:

The melody is now supported by a web of other voices, which fill out the slow rhythmic spaces, which make the theme more fluid, make it seem to float above a current of rhythm. In this he fills a void in A, he gives it a continuity it had longed for. (Or we had longed for?) But Beethoven is not just dealing with A-as-theme… in which case this coda could be written off as a fleshed-out variation, with added notes. Earlier in the movement we have had these kind of added-note variations, which are lovely but do not add, somehow, to the “meaning” of A; they merely help to beautify its stasis. So, added notes are not enough themselves to do what the coda does. I think Beethoven is dealing below the level of the theme, delving towards A-as-personality, towards A’s “reason for being,” which is its giving over of itself to its third part. Because Beethoven has put more voices in play … when the pattern of A heads into its third (searching) phase, the dangers and beauties of these extra voices can be unleashed. While the melody simply descends from the fifth scale degree down to the tonic, in the most predictable way–

–the other voices do unpredictable and extraordinary things, creating momentary breathtaking dissonances that become a part of the total feeling (the total image) of the phrase, which make the “simple” descent of the top line more deeply felt, which color the relinquishing of the movement’s slow energies with a tremendous intensity and regret. (To put it all analytically: the tenor line moves from A-flat to G, and this G clashes against the C in the top line, and then just after that, the alto line moves from E-flat to F through an amazing passing tone E-natural, and the moment of that E-natural, perched “between chords,” coloring the A-flat major tonic with its wrong-right-noteness, is the most memorable sonority of the passage for me, though it is the briefest.) While our “original A,” in its third phase, reached up melodically, to try to “escape” the registral space in which it was inscribed–

–the intensities of this last A are within, quite literally and music-theoretically: in the play of the inner voices. Whatever A is looking for, it finds in a different space, in a different solution; it searches, now, inside itself. (Is A a person? And how has A found this solution?) And this is it, my big why, the transformation of meaning that the coda does to me, the place where a streak of amazement clouds my brain’s connection to my hands and I find fulfillment in my ears, hanging on to those dissonances, my body buzzing … and knowing that “something has changed.” I would not be happy calling it by any music-theoretical name but I can trace how the music-theoretical names wind themselves into this changed moment.

Without ego, Beethoven adores his own moment; he winds us back up to E-flat in the top voice, and repeats the falling, fantastic gesture; now the structure and therefore the balance of power in A has changed: a struggle against the structure of A transforms itself into a prolonged farewell. And because he has now injected the falling five-line (E-flat down to A-flat) with such meaning, he then is able to repeat it, and call up the meaning without the meaning; we keep hearing those descending notes as the movement falls away, and though they are relatively plain, they are full: they symbolize the alteration we have just witnessed.

I have allowed myself to get carried away from the haven of identifiable notes to the scary world of interpretation and meaning, to suggest even that the movement interprets itself. Do you think, on a date, over a glass of white wine, in a noisy New York restaurant, I could manage to get this across? Because sometimes I think I need to go at least this deep to express why piano playing makes me happy. I really don’t want to be a jerk when people ask me about being a pianist, but sometimes I am anyway. Wait. I said that already.