Yours truly settled warmly into plush, red row W at Carnegie Hall, in a single seat at the end. I felt suspiciously glanced-at in my unaccompanied state (no, really, I have a life!) by my more elderly neighbors, and little suspected I had forgotten how K. 503 went. I thought I knew my Mozart (idiotic mistake), I smugly clutched my glossy program in preemptive assurance, and was later so abashedly, completely happy to have forgotten. Perhaps a professional classical pianist should not “be able” to forget 503, or should not admit it, but I really don’t care.

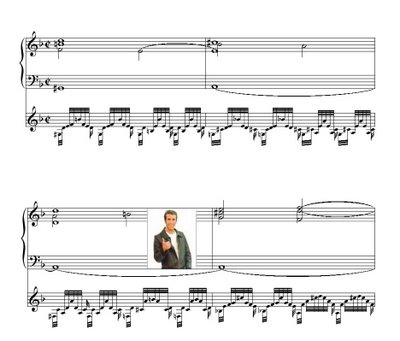

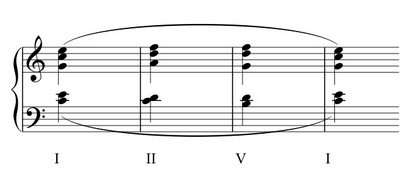

As all those “in the know” know, the piece begins with a rather grand gesture, taking its time through two 8-bar phrases to say “here I am.” (Benignly, nobly: not at all like, say, Jack Nicholson making his axed entrance near the end of The Shining). This Mozartean hello matched my memories; things were proceeding C-majorly, according to plan. There was even time to observe the similarity of these opening sixteen bars to the archetypal first four of the Well-Tempered Clavier:

But, as those “in the know” also know, the second 8-bar phrase is met at its conclusion by a little accident, a 2-bar extension. That’s the evil jargon we boring musicians use to express the idea of some “extra” measures at the end of a phrase, some kind of musical so-called superfluity. Extension, by the way, like so many music theory words, always seems like much too heartless a descriptor–it calls to mind a reprieve on a paper, or some add-on to a house, rather than some deliberate, beautiful volatility or asymmetry introduced into an evolving text. (Any readers who wish to propose a substitute name for “extension,” please do!) By the dastardly genius of Mozart these two bars are pretending to be no big deal, just a little echo, i.e. the same as the last two bars of the phrase, but in the minor key. They are, however, a big deal.

It was at this moment, just after the little echoing 2-bar minor key pivot, that my memory failed. Precisely at bar 19, I had no idea what was happening or was going to happen. And what seemed to be occurring onstage, in my ears, or brain, or near the ceiling, or wherever (no specific site for the happening) in this new unknown space seemed to be unbelievable, at least for a moment: a moment of creation and possibility. I say this without exaggeration. I felt: if that could happen–

why, anything could happen.

At intermission I ran into friends E and J and I tried to put my 503 excitement into words, but the words coming out of my mouth were flat and unsuccessful: something “wouldn’t take,” something elusive, crucial, misplaced.

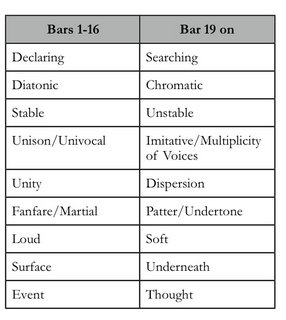

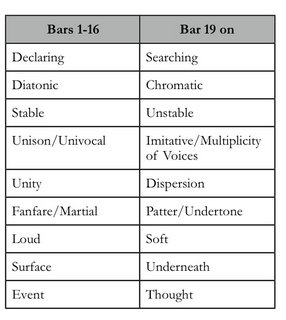

The basis of my happy disquiet was the feeling that there were two worlds, or two spaces. Mozart first poses the obvious, the overt and harmonically noble, the world of grand operatic entrances and declared high purpose (musically speaking, a world of slow unfolding I-II-V-I, circular perfect tonic-establishing entities). But then he immediately poses an undermining counter-text: a chromatic, agitated sequence in the minor key … Later on, in rampant caffeinated pursuit of the something that wouldn’t take, I indulged myself and tried to make a little table contrasting the two materials, grouping simple musical contrasts with associated metaphors:

I realized: this contrast, this shift to minor, would not nearly be so riveting if it did not seem to immediately and fundamentally strike at the very meaning of the opening material. (Bar 19 is not different in kind, but different in essence.) The first sixteen bars are all about certainty; they define, they enumerate, dispose, declare, set forth. They confine themselves; there is nothing to call a melody; there is simply harmonic assertion; there is no fancy, no diversion; the phrases are rhythmically identical, martial, symmetrical; they flirt with the conventional, even: the stodgy. Having gone to such lengths to dispel doubt at the outset, to create such a capital-O Opening, why suddenly intervene so early on, so disturbingly? I think this (rhetorical) question is near the crux of what was hitting me so hard about the piece.

I love those moments in music (but perhaps not so much in life) where you feel the ground has been pulled out beneath you, and inexplicable profusion ensues. Here in bar 19, certainties vanish, the musical ground vanishes–easy to define and enumerate (rhythm, major-key, texture, style)–and so also disappears a whole set of associated metaphors and ideas, which are harder to define. There is a sudden vacuum created by dispersed certainties, by this vanishing of meaning, and the thing Mozart creates, places in this vacuum, poses as a new possibility, is compelling, suspenseful, with unprecedented rhythmic energy, as if we were suddenly inserted in medias res into the really interesting part of some high, tragic drama, perhaps some moment of wonder or enigma in which various characters are at odds or wondering what is going on, a point just before some sort of climax or revelation. But (!) we are not at the climax of anything yet; we are barely settling in.

To rephrase, this moment is essentially double-edged: with one turning act Mozart creates and destroys; he creates a void only in order to fill it; he erases certainties in order to inscribe a new world. This world does not naturally coexist with the first, but it is “in communication” with it. It is not enough to say the turn of events is a surprise; it is more fundamental than that, a more revolutionary change of perspective. For some reason a ridiculous analogy comes to mind: those moments so common in movies where a character is standing on what he/she thinks is solid ground which turns out to be the hand of a monster, or a giant living tree (when the camera pans out), or the mouth of a whale. The walls are alive, the moment seems to say (the harmonic walls of the piece). There is something quickening in the heart of the piece which is antithetical, perhaps threatening, to it.

The magic, oft-invoked word in The Classical Style is “synthesis,” which the great 3 composers are said to have achieved. Mozart is praised for balance, proportion, grace, naturalness, ease, among so many other things. But I’m not sure this moment feels “organic” or “natural.” It is, rather, perfect but unnatural; it feels like a rhetorical interjection, the insertion of an Idea, the intervention of Thought. Its genius is not an easy flowering and development, but a sudden dizzying epiphany, a slippage of the mind.

Though the minor literally comes after the major, I’m not at all sure succession is the primary communicated meaning. To me it has a much more interesting relationship to time, something like coexistence, not narrative: the side-by-side vision of opposites. In other words, its message is not “this happens, then that happens” but rather something more disturbing: “it could just as well be this, or that.” And then when the major returns after our “bubble” of minor, does it seem to other people that it’s just a little too eager to assert itself, that its rising scales and triumphant sequences almost ring a bit hollow, too much of a muchness? Come to think of it, perhaps the opening was a bit too certain of itself as well. Why does it feel to some extent that that grand façade of the opening is peeled away to reveal this inner minor-key angst (raising questions of opening as façade, as curtain, questions of musical “truth”)?

I wouldn’t obsess over this moment if Mozart didn’t set me up for it. This first minor key intervention is so striking, that it forces us to ask: if it happened once, why not again? It isn’t really possible, in the Classical cosmos, to have something so extraordinary happen and then not to follow up on it (events follow, in the Classical world); and yet, and yet, this minor-key shift isn’t really typical of the Classical cosmos either; how can a non-Classical event be understood or developed in a Classical way? The listener is on high alert, even in the gilded, privileged confines of Carnegie Hall. And Mozart treats this uncertainty as a Theme, in the literary sense. The minor key keeps poking its head in, at regular and yet unpredictable intervals, enough to maintain a perpetual doubt-of-meaning, a constant waver in the fabric of the piece; it shimmers to show the dark minor side and shimmers back into major so that gradually you begin to perceive the work not as a solid entity but as a window, always promising or threatening another side. One can no longer say, comfortably, “this is an antithesis,” or smugly: this is major and this is minor. You begin to see yourself, as perceiver, as narrator, stuck between.

I caught myself doing something, I think … When bar 19 started and my familiarity dropped away, I caught my brain just for a second, like a swimmer in trouble, thrashing, trying to “make sense,” to map the pattern of the present onto the past. But I was unable to match the events either to my memories or to the first 16 bars of the piece: to anything at all. There it was: my mind was searching for a pattern connection between the two parts, and Mozart’s music at that moment depended on that activity, depended on its attempt and failure (its failure was Mozart’s success). I realized, part of the work of the composer is to create roadblocks to pattern perception, beautiful areas where the brain gropes blindly. I realized, too, part of what makes some music sound “too easy” or vapid is the absence of that kind of challenge; allowing the brain to laze around like a couch potato processing patterns in a daze. Mozart, the easy listening, un-dissonant composer (so I read in an interview in the program, aghast, as if this music wasn’t living and breathing dissonance nonstop), this long-dead Mozart was the one poking my brain, saying: stay awake, stay awake, keep living, you never know what will happen!