Today’s entry begins with a truly essential Ethical Question. Suppose you quip to a friend, “what am I? chopped liver?” Does the acceptable range of responses include: “Yes, in this context you ARE chopped liver”? Is it not understood that the question is rhetorical? Is it not just a little bit insulting, even linguistically, to be taken literally and dumped in your own metaphor? If your friend is staring at some extremely attractive fellow behind you, how does this make you feel? Please discuss.

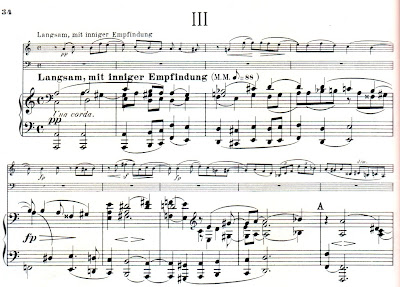

Something that is definitely not chopped liver literally, metaphorically, or in any other way is the slow movement of Schumann’s D minor Trio. (Please see: The Art of the Graceful Segue, by Jeremy Denk, Hyperion Books, 2031, p. 5,832.)

Of all the fantastic pieces I have played over the last six/seven weeks, this one has lingered the most powerfully and become kind of an obsession: I’ve gone all Fatal Attraction on it. Even more unhinged than usual, I have found it difficult to organize my thoughts into nice, neat paragraphs; so in the spirit of Schumann I will just present what I’ve got, how I’ve got it.

1. First issue: is this a melody?

Listen to this played on my out of tune piano:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

To some this may seem an unnecessary semantic issue (can you really define melody? isn’t it whatever you want to call it?), but I am not quibbling. The passage itself raises the question, and moreover: I think the presence of this disturbing question is essential to what the passage “means.” Imagine a melody archetype, and this ain’t it: a melody (whatever it is … in all its infinite playful variation … ) is more self-contained, more continuous, more “of a piece”; its peaks and valleys are clearer; it is more centered, supported, structured.

So, part of what makes this passage extraordinary is that it asks itself and the listener: what am I? It seems nearly anti-Melodic (or, perhaps more precisely, ante-melodic). One vision of Melody is as a sort of statement or declaration (“the violin states the theme, which is taken up by the cellos”, and so forth). But for me this is the crux: the violin here does not so much say something, as it wants to say something: something that won’t exactly take.

It makes me want to divide the world of melody into two parts: those that are, and those that aspire to be.

2. My hero, Roland Barthes:

To state that [a character] is “active or passive by turns” is to attempt to locate something in his character “which doesn’t take,” to attempt to name that something. Thus begins a process of nomination which is the essence of the reader’s activity: to read is to struggle to name …

… reading is absorbed in a kind of … skid, each synonym adding to its neighbor some new trait, some new departure: the old man who was first connoted as fragile is soon said to be “of glass“: an image containing signifieds of rigidity, immobility, and dry, cutting frangibility. This expansion is the very movement of meaning: the meaning skids, recovers itself, and advances simultaneously; far from analyzing it, we should rather describe it through its expansions … the generic word it continually attempts to join …

–from S/Z, tr. Richard Miller

Yes: the very movement of meaning! I love that phrase. I wish more performances felt like the movement of meaning.

3. Now consider violin plus piano:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The violin, often syncopated, appears to be bouncing off events in the piano, taking inspirations or stimuli from the beat. However, the piano part on its own is, I must confess, not particularly noteworthy. It appears to be–I can’t believe I’m saying this!–accompanying (I feel dirty even saying the word), providing chordal support for the violin; it avoids strong profile, directionality or purpose. Here and there a note or two leap out, but constantly (as if repeatedly accepting a “role”) the piano recedes into the background. In its texture, in its deference, it calls to mind an organist’s attempt to harmonize, to harmonize the violinist’s wayward hymn. But, a hymn should have a simpler melodic profile … and it usually starts on a beat …

So we have an unusual, paradoxical discourse, where both parties are looking to the other for a core of meaning, a supporting structure, and neither is giving it. They are both leaning against each other, but neither is solid. They are see-sawing, continually passing meaning off to each other, relinquishing. Pianist and violinist restlessly wander through. I can’t help but think Schumann wants them to feel lost together; he wants them to give each other false clues, non-answers; he wants them to skid and wipe out on accidents of meaning (and start again).

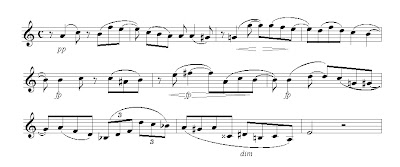

4. Let’s take the melody in sections…

It rises and falls:

It rises and falls again:

A couple more starts:

Then finally a sort of strange, culminating curlicue:

Such carefully composed impulsiveness. Rising, wanting, halting, falling: from these the question forms, what are we looking for? What is it to which each phrase aspires? If only some clear peak or solution would present itself! To the question “Is this a Melody?” we can add, “When will a Melody, or whatever it is, arrive?”

5. I think this is the sort of “melody” that could not exist before musical notation. It is too diffuse, too ready to fall apart, too unmemorizable: at once too self-similar and too dissimilar. It leans towards recitative, towards the stream of consciousness; instead of strong intervallic or motivic repetitions, each iteration works through “soft recollection”: each new version takes one element as given, unaltered, and changes everything else. We move forward barely, on thin threads of connection.

And this is the audacity of Schumann: taking something so personal, something that seems to be a collection of fits, starts, half-formed ideas, reflections, and making it a contrapuntal essence, making of it a “ground.” It is not a one-time event, something that unfolds randomly according to passing thoughts, though it appears to be so. For this non-melody recurs, won’t let go; its role (persisting) and its nature (dissolving) are at odds.

6. Each section of the “melody” lands, or more precisely does not land, on a half-cadence. Each segment, in other words, concludes inconclusively ( … is answered with the same non-answer.) Perhaps through the variety of the ways in which we get to the same place, we don’t quite realize it: we don’t realize at all how confined within a circle we are. Both this repetitive quality and the deceptive, disguising variety are written in. Schumann wants us to know, and not to know.

7. Schumann is painting exclusively on a bleak, uniform rhythmic canvas of eighth notes. There is power in deliberate omission; in the first nine bars not even a single sixteenth note is allowed to disturb or enhance the unfolding composite rhythm … We walk haltingly forward in this unstoppable, similar stream.

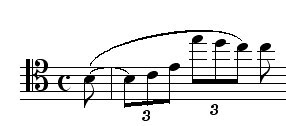

However, Schumann allows us one wonderful anomaly, in the form of rising triplets:

Appearing from nowhere … vanishing back into eighth notes … the violinist stumbles on these triplets like an accident (accidents of meaning!). Which adds something to the world we have seen, blurs its boundary; we skid and recover.

The triplets outline the Neapolitan chord (look it up, music theory scaredycats!), which, as always, by harmonic law, brings us to the half-cadence (not again! yes again). So in a harmonic sense (pedantic, literal) they are just part of the inevitable, the usual, the inescapable. But a contradiction: the new rhythm, the new B-flat “color,” if we allow ourselves some metaphor, or connotation, suggest some form of escape, either real or imagined.

Even the shape of the triplets colludes in this metaphor: rising from the lowest note of the melody … reaching up … this metaphor will reach us again, more profoundly.

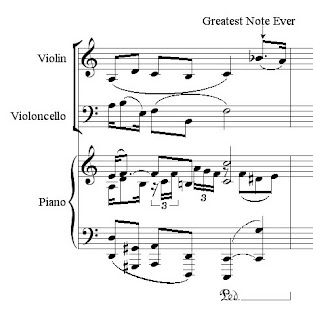

8. A most extraordinary moment: the violin passes off the “melody” to the cello. The cello appears here as epiphany, as the melody that the violin could not achieve. It poses a putative answer to the question: what have we been looking for? The timbre of the cello, too, brings color to the preceding monochrome. The cellist’s first notes, with their dotted rhythm–big event, rhythmic variety, disturbing the procession of eighth notes–appear to be a motto, a statement, a crystallization:

Yes, finally, something we can hold onto. But, in a bait and switch, the “real melody” has moved to the piano’s left hand…

Listen:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

This movement of voices is a transformation of meaning: melody becomes ground. Impulsive recitative reaches to its contradiction and becomes deep harmonic foundation, a startling fusion of opposites. This at once is a very archaic idea (voice exchange, invertible counterpoint, etc.), and a kind of ultramodern Romantic transgression, the violation of the antithesis, the impossible, extravagant juxtaposition.

9. What you “do not know” is that the pianist has begun his left-hand melody on F. What it means, of course, is that by the end of the statement (by the law of the “theme”) we will have to be in F; F is where we started, and that’s we are headed, no matter what.

But Schumann has finessed and elided the transition from statement to statement so that F major nearly vanishes into the cracks. The cello (masterstroke) enters on E, dissonant against the foundational F in the piano’s bass. (Compare this to the opening measures, where the violin simply, passively, enters within the A minor harmony supplied in the piano.) Aha, the cellist clearly doesn’t want you to know; he is an accomplice, helping to disguise the entrance of the “melody,” already murky in the bass of the piano, and to soften its key-defining function. I hear a lot of C major in here, though the key wobbles …

So, though we must arrive at F, this imperative is disguised, concealed. And because of this disguise and its attendant mystery, the moment of F arrival (inevitable, unstoppable, but also in some senses unforeseen) is an astounding revelation, one of the most beautifully crafted modulations to my mind in all of music. The famous melody-non-melody runs its course in the piano’s left hand, wends and wanders, and then–only at the last moments–appears fateful. At the cadence you slap your forehead and think, I knew it all along, or should have known; the obvious, unseen, perfect answer that comes to you …

10. I nominate, additionally, for One of the Most Beautiful Notes Ever Written, this B-flat in the violin at this cadential moment, just on the brink before the “Bewegter.”

Listen:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

B-flat comes at the end.

And yet it is not much; you might almost call it Romantic cliché. Just the appearance of the seventh of the dominant seventh, in music theory speak. To me it appears impossibly pure and beautiful, out of nowhere, a visitation; I feel as though I have never really heard a dominant seventh before. How is this possible? Perhaps: the point of all that preceded it, the wandering and halting, the hovering around half cadences, the thoughts and rethoughts, the seemingly aimless harmonic motions: all a world from which we can emerge, look, shake off our fog and see the simplest harmony as beautiful again, as real. Schumann created all that darkness and enigma: just for one fresh vision, one newly born harmonic child.

11. I deeply, murderously, envy the violinist that B-flat. At least I’ll concede that it wouldn’t be so beautiful on the piano (“doink”); the violin can nuance it so it appears, from above or below, the deus ex machina that it is; I could only imagine it, play it “as if it were possible.”

12. I am consoled that I get to play the little sixteenth-note triplets just before the violin’s B-flat, which herald it. They are an extraordinary, associative hinge, part of an ongoing musical “subplot.”

Remember our earlier triplets (see #7, above), the one anomaly/escape in the violin’s opening ten bars? In the bars that follow, Schumann creates a gradual rhythmic drama, an evolving profusion, a brewing rhythmic revolt. After the cello’s entrance more and more anomalies creep in, glimmers of escape propagate:

the dotted rhythm in 10:

then in bars 12 and 14, little unexpected 32nd note flourishes:

then in m. 15, the cello takes up the triplet idea (though it “belongs” rightly to the melody in the left hand of the piano):

and then, again, amazingly in the piano just before the F major “Bewegter,” I play these triplets:

which then transform themselves into the embryo of the new radiant F major, now built entirely on triplets, and inspire the violin to further, tenderer versions, and the cello to call back with triplets again in echoing response etc. etc.:

How wonderful. Into the bleak eighthnote world, a gradual awakening of rhythm, of life … And I get to play that lingering, hinging moment, the triplets “before the triplets,” a magical harbinger, the small enchanted zone between different worlds. Imagine the piece as an antithesis: on the one side, in bar 7, the triplets amidst the eighth notes, barely knowing what “they are about,” or even “why they exist.” And by the “Bewegter” we have crossed over to the other side, the land of ecstatic triplets … Gradually they understand, they dawn to their purpose … Indulge me in one last metaphor. In the opening section, the triplets are a mere symbol, a cipher; they stand for something but what? (Where do they come from, why are they here?) By the middle section, the symbol is no accident; it is interpreted and released: the cipher is uncoded, and the symbol becomes reality (… the very movement of meaning …)

13. The note I love in the violin, which ushers in the new section: B-flat. The “escape harmony” of the violin in its first phrase: the Neapolitan, built on B-flat as root. A coincidence that is no coincidence. These B-flats call to each other across the many measures that separate them.

14. Let’s take a long view.

1) The opening violin melody searches.

2) The cello entrance appears to be an answer, but is not; it too disintegrates into possibilities.

3) Even at the F major “Bewegter” things appear still to be expectant, the movement is living ecstatically towards something … and then …

4) falls back into the same thing; the opening melody returns several times, each less energized than the last, everything falls back into familiar stasis…

… the overall arc of the movement (rising, becoming, falling, returning) thereby mirrors its smallest, defining gesture, the opening two measures, say, of the violin.

15. What I so often wish I could communicate with audiences through my playing is this active self-referential drama, in which the music addresses itself, tries to make itself into something, finds itself at risk of falling apart … etc. etc. If you press play on the CD player and the music comes to you like water from a faucet, don’t you feel there is something in the medium that takes something for granted, in which this sort of risk does not figure? Recorded risk seems like a bit of a contradiction. I find myself even in certain concerts listening that way, as though the music were just flowing on by, happening externally, like something I can dip my hands into or not; something which is “just music.” After all, it’s just music. You hear that in rehearsal sometimes when people are tired of talking about a passage, and I empathize without agreeing. Music can be admired and consumed in this way but not loved; you lose the element of music-about-music, the magic boundary where, like every human being or endeavor, it becomes self-aware, turns and reflects on itself.

16. This movement reflects on itself in so many ways, even for example in matters of genre. I imagine Schumann is channeling some late chorales of Beethoven, like the slow movement of the last Cello Sonata (Op. 102 #2)… but, even in emulation, this hymn is not satisfied with itself. It is provisionally hymnic but not a hymn. As a performer, I find myself torn between two opposed motivations or styles of playing: an inevitable procession of the notes (the “hymnic” style, perhaps even a “Classical” style) versus a wandering, hesitating approach (the “Romantic,” the lost soul). The notes seem to suggest both. And only in the play of difference, in my own hesitation between these possibilities, do I feel I can finally realize something of the score’s intent.

17. Grappling, the struggle to name … to me Schumann is the genius who explored and basically invented in musical terms the struggle towards coherence or expression, and he is greater for having often “failed.” Plainly, in many cases, his goal was failure. His most extraordinary phrases are not formed, but wish to form; he understands that when music passes from action to object already some of its charm is lost.

Beethoven adores his themes and motives for their functioning; for all his genius, he tends to fetishize what they may build or achieve. But Schumann loves precisely their dysfunction, what they cannot do, what they will never be able to do: their unreachable prospects.