By now, we are all familiar with the recent performance of Miss Teen South Carolina. (I know what you’re already thinking: “why, Jeremy, why from the shelter of your Upper West Side comfort, hemmed in by prolific ATMs, would you feel the perverse need to pile any more scorn upon this poor girl? Just get a puppy if you need something to do!”) I think it helps to divorce oneself from the visual component of this event, and focus on the pitiless words themselves:

Q: Recent Polls indicate a 5th of Americans can’t locate the US on a world map. Why do you think this is?

A: I personally believe that US Americans are unable to do so because some people out there in our nation don’t have maps and I believe that our education like such as in South Africa and the Iraq everywhere like such as and I believe that they should our education over here in the US should help the US or should help South Africa it should help the Iraq and the Asian countries so we will be able to build up our future for us.

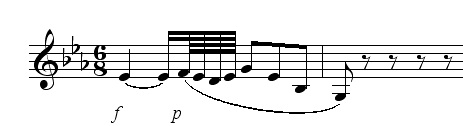

… and they say poetry is dead! Grammar itself cowers in terror before this free-ranging masterpiece. Most readings so far of this text seem to focus on its evanescent “meanings” (or ambiguities of same), conforming—even without being aware of it—to workaday conceptions of coherence. I, however, would like to propose a different methodology, yielding quite different, even shocking results. The proper vehicle for addressing this text is musical, not semantic or grammatical (though it refers to the semantic and grammatical in order to create its pseudo-musical paradigms). It begins innocently enough, with seeming Mozartean grace:

Antecedent phrase: I personally believe the US Americans are unable to do so…

(moving from tonic to dominant)

Consequent phrase: because some people out there in our nation don’t have maps.

(dominant back to tonic)

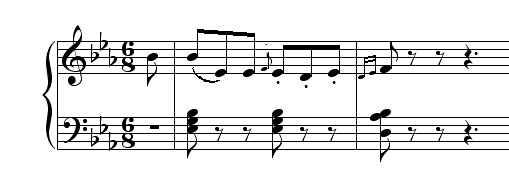

The tremendous idiocy of the content should alert you: everything is a façade. Falstaffian glee lurks behind her glassy eyes. The simple up and down of this statement (a Newtonian, classical “pose”) lulls you into knowing complacency, into a careless condescension, prematurely, leaving you vulnerable to the surprising twists and turns to come. The meaning of the sentence (incidental) conceals a web of musical, motivic connections that then become the “subject” of the ensuing development.

Theme One: personally, believe, I, our (symbolizing possession, self-centeredness, isolation)

Theme Two: some, out there, US Americans (paradoxically creating “other” out of “we”)

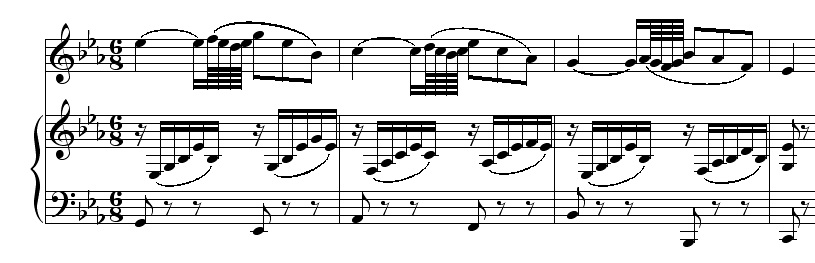

What follows is an intertwining, a composing-out (Durchführung) of these two themes. If the opening sentence can truly be understood sequentially-semantically, the middle can only be understood as music, as the reiteration of sounds (proper names, fillers) which, in their peculiar order, jangle against meanings only accidentally, if at all. She has absorbed the lessons of Verlaine, but has transported them to Applebee’s. Cunningly she promises parallel construction (“I believe that our education”), indicating she might begin another “sensible” phrase, invoke another antecedent and drop another meaning-bomb; but then, with a deceptive cadence, she diverges into what in Haydn would be termed a purple patch:

like such as in South Africa and the Iraq everywhere like such as

This is where her genius shines absolutely: she exploits “like such as,” a musical tautology (and what else is music but beautiful tautology?), in order to bracket the other: “in South Africa and the Iraq everywhere.” These other nations are a mere ironical neighbor-tone to the central message—“like such as”—if the central message is not, in fact, the very bracketing construction itself. To put it another way: “like such as” is a beautiful nonsense phrase intended (if we are not overreaching) to symbolize the nonsensical demarcation of the other.

Now you see, once the musical proposition has been set up, the rest falls into place. What seemed like chaotic babble is now a disturbingly brilliant elided phraseform. For instance:

and I believe that they should our education over here in the US

Here she recalls the deceptive beginning of the last phrase, she reechoes “belief” as motive, she mixes in a bit of anti-grammatical subversion (“should our”—where is my missing verb? you could sit up all night wondering … “improve” might be a possibility, but nah, it’s too easy!), and strums upon “our” and “here,” the familiar themes. Then, the masterstroke:

should help the US

If there was any doubt of her subversive and musical intent, this haunting re-echo (say it to yourself: “should our education over here in the US/should help the US”), or “extension,” in music theory speak, should quench it forever. The mirrored, Alice-in-Wonderland, navel-gazing quality of “Americanism” has never been more poignantly evoked; it falls away in fragments. The reduplication of “should” and “US” inevitably calls to mind the “like such as” from before, and reminds us that as much as we would like to define an other, our definitions merely boomerang back upon ourselves. The rest is mere ramification, teasing out, the thud of trajectories hitting home:

or should help South Africa

it should help the Iraq and the Asian countries

so we will be able to build up our future

for us

The harmony ends ambiguously; its Tristan chord is not resolved, but worked into further contortions, chromatic notes beyond knowing. Do you hear it: “help” and then again “help” and then again “help”? There is a kind of helpless quality, if you will, to this helping: its attempt, in various clauses, to reach some definitive meaning, to find a site, a place to stanch the wound, to heal the bleeding world. And at last, the parenthetical tautology: our future/for us. A final gasp, in undertone: a guttural reiteration of narcissism, relinquishing meaning and sound to the chaotic consequences of self.