One of the unexpected perks of playing with the New World Symphony is that its music director may assign you reading material. Assigned reading is my fantasy. (One of them, anyway.) Lock me in a room, with snacks, maybe a few well-chosen posters; tell me I have to read 6,000 pages before tomorrow and ensure I have no other decisions to make. Hours and hours spent poring against a deadline on the arch in Tappan Square in Oberlin, Ohio; bare feet across the marble of the arch; fingers scraping across the clean smooth page, fresh from the bookstore; no goals but pages and escape and beauty; your eyes wander, grab glimpses of ambling reality, and then you force them back deliciously, painfully into the word world.

Now that Halloween is over, the holidays steal upon us. In my assigned reading, I came upon this heartwarming holiday scene, which I thought I would share with all of you:

You must surely know that on this season, Christmas and New Year’s, even though it’s so fine and pleasant for all of you, I am always driven out of my peaceful cell onto a raging, lashing sea. Christmas! Holidays that have a rosy glow for me. I can hardly wait for it, I look forward to it so much. I am a better, finer man than the rest of the year, and there isn’t a single gloomy, misanthropic thought in my mind. Once again I am a boy, shouting with joy. The faces of the angels laugh to me from the gilded fretwork decorations in the shops decorated for Christmas … But after the holidays everything becomes colorless again, and the glow dies away and disappears into drab darkness.

Every year more and more flowers drop away withered, their buds eternally sealed; there is no spring sun that can bring the warmth of new life into old dried-out branches. I know this well enough, but the enemy never stops maliciously rubbing it in as the year draws to an end. I hear a mocking whisper: “Look what you have lost this year; so many worthwhile things that you’ll neveer see again. But all this makes you wiser, less tied to trivial pleasures, more serious and solid—even though you don’t enjoy yourself very much.”

Every New Year’s Eve the Devil keeps a special treat for me. He knows just the right moment to jam his claw into my heart, keeping up a fine mockery while he licks the blood that wells out. And there is always someone around to help him, just as yesterday the Justizrat came to his aid. He (the Justizrat) holds a big celebration every New Year’s Eve, and likes to give everyone something special as a New Year’s present. Only he is so clumsy and bumbling about it, for all his pains, that what was meant to give pleasure usually turns into a mess that is half slapstick and half torture.

I walked into the front hall, and the Justizrat came running to meet me … He smirked at me in a very strange way and said, “My dear friend, there’s something nice waiting for you in the next room.” …

I felt that sinking feeling in my heart. Something was wrong, I knew, and I suddenly began to feel depressed and edgy. The the doors were opened. I took up my courage and stepped forward, marched in, and among the women sitting on the sofa I saw her.

Yes, it was she. She herself. I hadn’t seen her for years, and yet in one lightning flash the happiest moments of my life came back to me, and gone was the pain that had resulted from being separated from her.

What marvellous chance brought her here? What miracle introduced her into the Justizrat’s circle? … I didn’t think of any of these questions; all I knew was that she was mine again.

I must have stood there as if halted magically in midmotion. The Justizrat kept nudging me and muttering, “Mmmm? Mmmm? How about it?”

I started to walk again, mechanically, but I saw only her, and it was all that I could do to force out, “My God, my God, it’s Julia!” I was practically at the tea table before she even noticed me, but then she stood up and said coldly, “I’m so delighted to see you here. You are looking well.” And with that she sat down again and asked the woman sitting next to her on the sofa, “Is there going to be anything interesting at the theatre the next few weeks?”

You see a miraculously beautiful flower, glowing with beauty, filling the air with scent, hinting at even more hidden beauty. You hurry over to it, but the moment that you bend down to look into its chalice, the glistening petals are pushed aside and out pops a smooth, cold, slimy, little lizard that tries to cut you down with its glare.

[… the party continues for a while…]

Julia picked up a sparking, beautifully cut goblet and offered it to me, saying, “Are you still willing to take a glass from my hand?” “Julia, Julia,” I sighed.

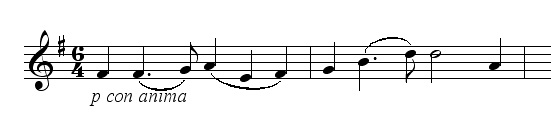

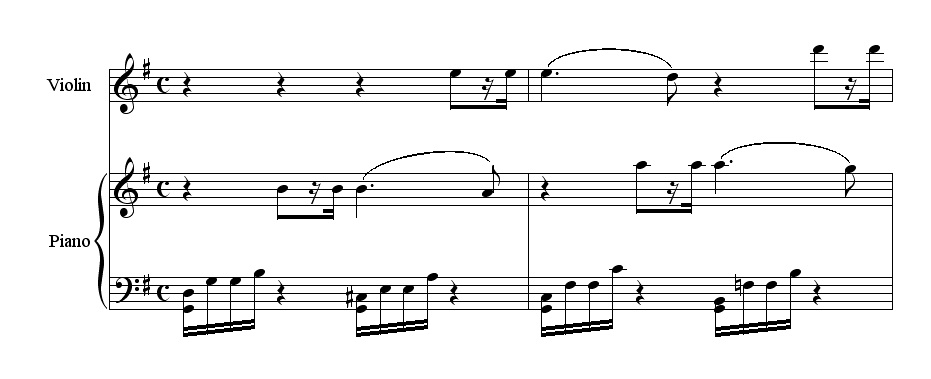

As I took the glass, my fingers brushed against hers, and electric sensations ran through me. I drank and drank, and it seemed to me that little flickering blue flames licked around the goblet and my lip. Then the goblet was empty, and I really don’t know myself how it happened, but I was now sitting on an ottoman in a small room lit only by an alabaster lamp, and Julia was sitting beside me, demure and innocent-looking as ever. Berger had started to play again, the andante from Mozart’s sublime E-flat Symphony, and on the swan’s wings of song my sunlike love soared high. Yes, it was Julia, Julia Herself, as pretty as an an angel and as demure; our talk a longing lament of love, more looks than words, her hand resting in mine.

“I will never let you go,” I was saying. “Your love is the spark that glows in me, kindling a higher life in art and poetry. Without you, without your love, everything is dead and lifeless. Didn’t you come here so that you could be mine forever?”

At this very moment there tottered into the room a spindle-shanked cretin, eyes bulging like a frog’s, who said, in a mixture of croak and cackle, “Where the Devil is my wife?”

Julia stood up and said to me in a distant, cold voice, “Shall we go back to the party? My husband is looking for me. You’ve been very amusing again, darling, as overemotional as ever; but you should watch how much you drink.”

The spindle-legged monkey reached for her hand and she followed him into the living room with a laugh.

“Lost forever,” I screamed aloud.

“Oh, yes; codille, darling,” bleated an animal playing ombre.

I ran out into the stormy night.

Thank you, E.T.A. Hoffmann.