As a boy, Joaquin always awoke with the dawn, and it seemed to him, morning after silent morning, that he woke precisely at dawn’s center, at the unknowable fulcrum of a giant quake of light. In those few free minutes before the pastor came to gather him up, smelling of incense and aftershave, before these adult smells tangled his reason, he let his hands dangle over the edge of the balcony and glanced over the city draped in mist and green and lingering pools of darkness and watched the mountain etch itself against retreating folds of purple and he heard the murky water in the fountain of the villa next door, slapping against stones and frogs … an uneven, dilapidated music. Many years later, backstage at the Palacio of Fine Arts, after an exhausting concert, with a sea of blue-haired ladies around him, it came to him, that what seemed to be missing from his childhood was a sense of reasons why, that he could never stop asking why people were doing things, and each reason he added to the pile in his mind displaced the last but one, so that he could never get anywhere, like in his dreams, but for real.

But each day in those days the dawn was beautiful and like the stroke of a clock for thirty-two straight days the pastor would swing open the door, holding two banana leaves in which were wrapped steaming hot plaintains with cracklings of pork and unnamable spices. These they would open while they walked, while his parents slept, and they would wander the awakening streets and talk of causes as if they had nothing to do with effects.

The pastor was also the town’s music teacher. He had dropped out of Conservatory in Buenos Aires, it was said, because of a ferocious love, which burned him from the center out and left him dumped in this town, hawking religion. Most of the children asked at their lessons “why do we have to practice scales?” but Joaquin had asked “why do scales exist?” and that is when the pastor decided to come and visit him every day, just to talk. That question could get you put in the nuthouse, he replied. Scales exist (he continued, adopting a pedantic tone) because the beauty of the world is divided into parts. But the boy scowled, and the pastor chuckled, as if he’d known all along that the boy wouldn’t accept this first answer. He rolled his eyes upwards, intoning, Oh Lord deliver me from this difficult child! But the boy refused to blink, and the pastor ruefully conceded: maybe division is the currency required to purchase the beauty of the world. He pressed seven worthless coins into the boy’s palm.

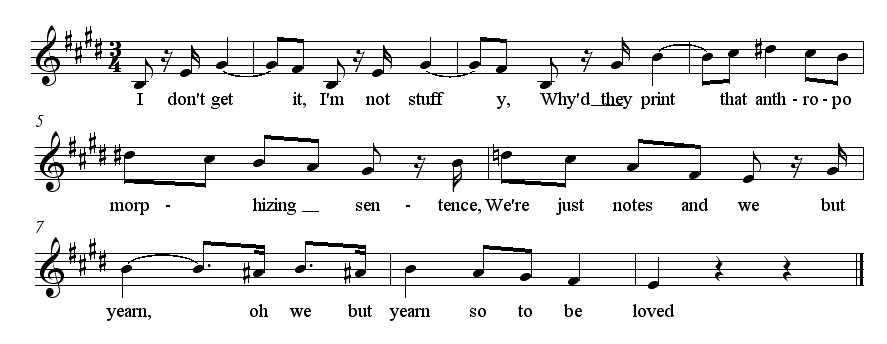

The streets at dawn were filled with women sweeping stoops, and men in their suits brushing dust off their sleeves, striding purposefully with empty eyes. Joaquin and the pastor walked calmly and made quite a distinct impression. The pastor made a habit of singing, over and over, a four-note idea …

and while he sang it, his fingers stroked his long, greying mustache from one end to the other. Joaquin loved to watch him sing and stroke his mustache at the same time, and though he preferred silence, could not stop himself from singing along.

Every so often the pastor would tire of this idea and he would sing …

Then he would look at Joaquin, ask him to explain the relationship between the two ideas. And Joaquin would look reproachfully at him, and say, Father, I am no idiot, why do you ask me only the simplest questions? The one answers the other, as I answer you.

The pastor ignored him, and said “the world is full of arbitrary, idiotic lists. Lists are the easiest possible thing, possibly the only possible thing … lists of events, lists of ideas, sequences of things. Enumeration is never meaning. The purpose of life seems to decompose into never-ending lists. But perhaps one could write a list that would be better than all the rest, not just a sequence, somehow more … by some miracle …”

His voice trailed off and then he resumed in a more teacherly voice, “You see that is one way to understand the whole thing, Joaquin, as a list of questions that have answers, beautiful answers, but most people don’t understand how questions and answers can be beautiful until music teaches them. Music teaches the word how to reply. It is the most alluring grammarian. It is a harmless world where effects can happen without anyone getting hurt and that is where we can learn certain laws which are not laws, where only our souls can be arrested.”

Joaquin sniggered inwardly at the sentimentality of the older man at these times, for which he never later forgave himself. Old men gathered at street corners on rickety folding chairs sniggered too, saying, “What are these two serenaders doing wandering the streets? Neither of them can be seeking a woman …” But their high-pitched voices were tinged with jealousy.

The pastor and child always circled the city differently; they loved byways and fishy alleys; they never thought, not once, of shortening their journey, but only of the ways of lengthening it, or varying it. At the same time, they always arrived somehow after an hour at the Plaza, where the pastor always pretended to be surprised, and proposed as if by accident, innocently, “why don’t we sit and have a drink”? Sweat shone on his balding head.

They took a table at the cafe, which was then releasing its breakfast patrons, leaving behind just a few desultory remainders without jobs, without lives. The pastor always ordered an espresso, and told the waitress to bring Joaquin a beer, and she brought juice instead. A pattern, a recurring joke, a catechism. They watched the sun begin to light the statue and the sad gazebo, lying in wait for the murderous heat of the day, and listened to the greedy birds. Of all these ritual mornings, however, Joaquin remembered one in particular. He was staring deeply at the brown fingers of foam clinging to the inside of the pastor’s cup, wondering for the hundredth time what coffee tasted like. Its dark smell hung in the air, icon of his future. The pastor said, “look over there, right now, that is what I have been trying to express to you.”

And Joaquin turned his head to see, at a nearby table, a fat man in a white suit and a woman in a simple green dress. The woman was fanning herself. But as if from some mysterious signal, she closed her fan. And as she did, Joaquin caught a glimpse of her dark, beautiful eyes, moving. His skin tingled. He fell into the pools of her eyes, splashed around in their depths. He had a brief sense of youthful eternity. Then the fan opened up again, piece by piece; the fat man glowered at him, and he turned away.”What did you think of that?” the pastor said.

Joaquin was silent. “That woman,” he continued, “should not be allowed to carry that fan, it is a deadly weapon. Just the way she holds it, the way she draws it aside to reveal her face …”

Joaquin was still unable to speak.

“The fan is a veil,” the pastor said, “and what I want so much for you to understand, Joaquin, are you listening?, is this linked principle of unfolding and unveiling. Imagine that each slat of the fan is a musical note. Those notes are connected, they are held, like the slats of the fan are connected at the bottom, so that the sequence, the list of them, describes not a line, but a circle …”

Joaquin was lost in his own meditations, but the pastor kept on going about the line, the clusters of notes, the semicircles wanting to be circles, and the idea of the original sin of thought, of music, being that the scale cannot go on forever, and the mystery of wondering what is behind the veil of the connected notes which draws aside, and before he knew it they were at home again. The pastor was playing on the clavichord a few phrases, over and over. Joaquin, Joaquin, he said, listen to me. The first phrase ends thus (and he played):

And so too, slightly altered, the second phrase:

Don’t you see too, how this is a mirror, Joaquin, a mirror of the bassline we have been singing all this time, the completion of the bassline’s first four notes, as if the bass were sad (he chuckled slightly) that it could not finish its scale? The melody completes the bass, but since they are made of different stuff, Joaquin, the merger is impossible.

And he keeps unfolding these five notes in front of us, again and again … why?

But the boy could not answer. His eyes were already blurred with tears for reasons he could not quite fathom. It had something to do with the eyes of the woman and the pastor passing over those notes, the little beautiful dissonant notes in between the fifth, his hearing of this recurrence, this repeated unveiling. “I see you understand,” the pastor said, “but the most beautiful revelation is at the end, here …” and he played the following bass …

“You see how the bass outlines a descending fifth, then stops, then resumes, then stops, then resumes … the chain seems to end, but keeps finding another link, another way to go on … another temporary illusion of endlessness.” Joaquin was completely overcome at this moment, and the pastor put his arms around him, and unluckily his parents then suddenly entered, saw the boy weeping, out of control.

That is how their walks ended, how that whole season of his life ended. His parents forbade the pastor to come again, promised him they would find another music teacher, one who did not make him cry. But you’re wrong, he told them, I want a music teacher who makes me cry. They ignored him. Some days later the whispers on the street were that the pastor had left town, suddenly, strangely, leaving no notice.

But a small envelope found itself on Joaquin’s windowsill.

“Dear boy, there is one more thing I wanted so much to say to you. Remember the woman with the fan? I am sure you remember, I am sure you will never forget.

Conjure that moment again in your mind, but imagine that the woman is not there. Get rid of the fat man too, of course. Imagine there is just the fan in front of you, moving in the way it was moving when she held it, but when it is drawn aside, there is nothing, there is no way of seeing what’s behind it, because the holder of the fan is invisible, or because she does not exist … for whatever reason, it does not matter, this is irrelevant.

So, Joaquin, do you see it: only the fan moving? For that is the art of musical interpretation, my dear boy — to deduce the woman from the motion of the fan.”